Mediated transport

Mediated transport refers to transport mediated by a membrane transport protein. Substances in the human body may be hydrophobic, electrophilic, contain a positively or negatively charge, or have another property. As such there are times when those substances may not be able to pass over the cell membrane using protein-independent movement.[1] The cell membrane is imbedded with many membrane transport proteins that allow such molecules to travel in and out of the cell.[2] There are three types of mediated transporters: uniport, symport, and antiport. Things that can be transported are nutrients, ions, glucose, etc, all depending on the needs of the cell. One example of a uniport mediated transport protein is GLUT1. GLUT1 is a transmembrane protein, which means it spans the entire width of the cell membrane, connecting the extracellular and intracellular region. It is a uniport system because it specifically transports glucose in only one direction, down its concentration gradient across the cell membrane.[3] An example of a symport mediated transport protein is SGLT1, a sodium/glucose co-transporter protein that is mainly found in the intestinal tract. The SGLT1 protein is a symport system because it passes both glucose and sodium in the same direction, from the lumen of the intestine to inside the intestinal cells.[4] An example of an antiport mediated transport protein is the sodium-calcium antiporter, a transport protein involved in keeping the cytoplasmic concentration of calcium ions in the cells, low. This transport protein is an antiport system because it transports three sodium ions across the plasma membrane in exchange for a calcium ion, which is transported in the opposite direction.[5][6]

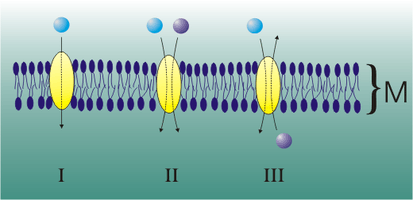

| Types of Mediated Transporters | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniporter (I) | Symporter (II) | Antiporter (III) | |

| Allows transportation of one solute at a time | Transports solute and countertransported solute at the same time and in the same direction | Transports the solute in one direction while the countertransported solute is moved the opposite direction in or out of the cell[7] | |

Mechanism of transport. A molecule will bind to a transporter protein, altering its shape. The change of shape or other added substances such as ATP will, in turn, cause the transport protein to alter its shape and release the molecule onto the other side of the cell membrane.[8]

Types of Transport[9]

| Facilitated Diffusion | Active Transport |

|---|---|

| No energy source needed | Requires ATP |

| Moves substance from high to low concentration | Can create concentration gradients and moves molecules from low to high concentrations[10] |

| Transport Protein required | Transport Protein required |

References

- Lodish, Berk, Zipursky, H,A,SL (2000). Molecular Cell Biology. 4th edition. New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. Ch. 15.

- "Protein-Mediated Transport". content.openclass.com. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- "GLUT1 - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Reference, Genetics Home. "SLC5A1 gene". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Reeves, J. P.; Condrescu, M.; Chernaya, G.; Gardner, J. P. (November 1994). "Na+/Ca2+ antiport in the mammalian heart". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 196: 375–388. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 7823035.

- "Sodium-Calcium Exchanger - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- WOLFERSBERGER, MICHAEL (1994). "UNIPORTERS, SYMPORTERS AND ANTIPORTERS" (PDF). Department of Biology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA. 196: 5–6. PMID 7823043.

- Grassl, Steven M. (2001-01-01). "Mechanisms of Carrier-Mediated Transport: Facilitated Diffusion, Cotransport, and Countertransport". Cell Physiology Source Book: 249–259. doi:10.1016/B978-012656976-6/50108-6. ISBN 9780126569766.

- Byers; Sarver, James P.; Jeffery G. (2009). Pharmacology Principles and Practice. Academic Press. pp. 201–277.

- Hille, Bertil (2001). Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 23 Plumtree Road, Sunderland, MA, 01375: Sinauer Associates, Inc. p. 359.CS1 maint: location (link)

External links

- Voet, Donald; Voet, Judith G.; Pratt, Charlotte W. Fundamentals of Biochemistry: Life at the Molecular Level. Chapter 10. "Membrane Transport" p. 286-310