Measures of gender equality

Measures of gender equality[1] or (in)equality are statistical tools employed to quantify the concept of gender equality.[2][3]

There are over three hundred different indicators used to measure gender equality, as well as a number of prominent indices.[4] The most prominent indices of gender equality include UNDP's Gender-related Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), introduced in 1995. More recent measures include the Gender Equity Index (GEI) introduced by Social Watch in 2004, the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) developed by the World Economic Forum in 2006, and the Social Institutions and Gender Index of OECD Development Centre from 2007.[4][5]

Indicators

Sample indicators of gender equality include gender-sensitive breakdowns of the number or percentages of positions as legislators or senior managers, presence of civil liberties such as freedom of dress or freedom of movement, social indicators such as ownership rights such as access to banks or land, crime indicators such as violence against women, health and education indicators such as life expectancy, educational attainment, and economic indicators such as gender pay gap, labor force participation or earned income.[4]

To reduce the number of individual statistics to be cited, several indices composed of aggregated indicators are commonly used.[4]

Indices

Gender-related Development Index

GDI is a gender-focused development of the Human Development Index, measures the development levels in a country corrected by the existing gender inequalities.[5][6] It addresses gender-gaps in life expectancy, education, and incomes. It uses an “inequality aversion” penalty, which creates a development score penalty for gender gaps in any of the categories of the Human Development Index which include life expectancy, adult literacy, school enrollment, and logarithmic transformations of per-capita income. In terms of life expectancy, the GDI assumes that women will live an average of five years longer than men. Additionally, in terms of income, the GDI considers income-gaps in terms of actual earned income. The GDI cannot be used independently from the Human Development Index (HDI) score and so, it cannot be used on its own as an indicator of gender-gaps. Only the gap between the HDI and the GDI can actually be accurately considered; the GDI on its own is not an independent measure of gender-gaps.[7]

Gender Empowerment Measure

GEM was developed at the same time as GDI, but is seen as more specialized.[5] It included dimensions not present in GDI (and correspondingly, HDI), such as rights and access to power.[4] The GEM was designed to measure "whether women and men are able to actively participate in economic and political life and take part in decision-making". It tends to be more agency focused (what people are actually able to do) than well-being focused (how people feel or fare in the grand scheme of things). The GEM is determined using three basic indicators: Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments, percentage of women in economic decision making positions (incl. administrative, managerial, professional and technical occupations) and female share of income (earned incomes of males vs. females).[8] The GEM is thought to be a valuable policy instrument because it allows certain dimensions that were previously difficult to compare between countries to come into international comparison.[9]

As time passes, and these measures (the GDI and the GEM) are applied year after year, debate has arisen over whether or not they have been as influential in promoting gender-sensitive development as was hoped when they were first created. Some of the major criticisms of both measures includes that they are highly specialized and difficult to interpret, often misinterpreted, suffer from large data gaps, do not provide accurate comparisons across countries, and try to combine too many development factors into a single measure. The concern then arises that if these indices are not well informed, then their numbers might hide more than they reveal.[7] They do not measure the relative position and status of women in relation to men, but rather absolute levels of income per capita or human development. Mills (2010) goes as far as to say that “although they are often touted as key measures of gender (in)equality, most experts agree that they are in fact not measures of gender inequality at all.“[6]

Gender Equity Index

Gender Equity Index (GEI) has been developed to measure situations that are unfavorable to women. It is designed to facilitate international comparisons by ranking countries based on three dimensions of gender inequity indicators: education, economic participation and empowerment. Due to its focus on socioeconomic opportunities, it has been criticized for ignoring underlying causes of gender inequality such as health.[5]

Global Gender Gap Index

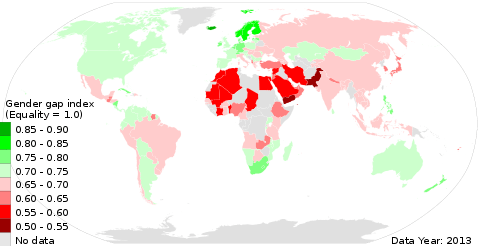

Another popular and widely reported global gender gap index is the Global Gender Gap Index, published in the Global Gender Gap Report. This measure was introduced by the World Economic Forum in 2006 and has been published yearly since. The index is based on the level of female disadvantage (so it is not strictly a measure of equality), and is intended to allow comparative comparison of gender gap across different countries and years. Increased scores over time can be interpreted as the percentage of the inequality between women and men that has been closed. The report examines four critical areas of inequality between men and women in approximately 130 economies around the globe, focusing on economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, political empowerment and health and survival statistics.[10]

GEI and GGP measures are conceptually more broader. GEI focuses on socioeconomic opportunities, but it has been criticized for ignoring underlying causes of gender inequality such as health.[5] GGI is the most comprehensive, through it in turn has been criticized for being too broad.[5]

Social Institutions and Gender Index

To address the perceived inadequacies of those four indices, in 2007 the OECD Development Centre introduced a Social Institutions and Gender Index (SIGI), a composite indicator of gender equality that solely focuses on social institutions that affect the equality between men and women, as well as on the four dimensions of family code, physical integrity, ownership rights and civil liberties. Social institutions comprise norms, values and attitudes that exist in a society in relation to women.[5] SIGI's authors argue that it is "the only index that focuses on the underlying sources of gender inequality", through they note it is indented to supplement, not replace, the aforementioned other existing measures; they also note that this topic is likely too complex for a single indicator, and recommend a multi-indicator approach for any studies that want to aim to be more comprehensive.[5] The tool has been praised for being a valuable measure for developing countries, but criticized as less applicable for the developed ones.[6]

See also

References

- Murdock, Daniel. "Economic Measures of Gender Inequality". Study.com. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- "Using data to measure gender equality | UN DESA | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs". www.un.org. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- "How to measure gender equality?". sciencenordic.com. Retrieved 2018-10-26.

- Hawken, Angela; Munck, Gerardo L. (24 April 2012). "Cross-National Indices with Gender-Differentiated Data: What Do They Measure? How Valid Are They?". Social Indicators Research. 111 (3): 801–838. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0035-7.

- Denis Drechsler; Johannes Jütting, Louka T. Katseli (22 September 2008). "Social Institutions and Gender Equality: Introducing the OECD Gender Institutions and Development Data Base (GID-DB).". Statistics, Knowledge and Policy 2007 Measuring and Fostering the Progress of Societies: Measuring and Fostering the Progress of Societies. OECD Publishing. pp. 472–474. ISBN 978-92-64-04324-4.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mills, Melinda (2010). "Gender Roles, Gender (In)equality and Fertility: An Empirical Test of Five Gender Equity Indices". Canadian Studies in Population. 37 (3–4): 445–474. doi:10.25336/P6131Q.

- Klasen, Stephan (2006). "UNDP's Gender‐related Measures: Some Conceptual Problems and Possible Solutions". Journal of Human Development. 7 (2): 243–274. doi:10.1080/14649880600768595.

- Cueva Beteta, Hanny (2006). "What is missing in measures of Women's Empowerment?". Journal of Human Development. 7 (2): 221–241. doi:10.1080/14649880600768553.

- Charmes, Jacques; Wieringa, Saskia (2003). "Measuring Women's Empowerment: An assessment of the Gender-related Development Index and the Gender Empowerment Measure". Journal of Human Development. 4 (3): 419–435. doi:10.1080/1464988032000125773.

- Klasen, Stephan; Schüler, Dana (2011). "Reforming the Gender-Related Development Index and the Gender Empowerment Measure: Implementing Some Specific Proposals". Feminist Economics. 17 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1080/13545701.2010.541860.

Further reading

- Klasen, S. (2007). "Gender-related Indicators of Well-being". In McGilivray, M. (ed.). Measuring Human Well-Being: Concept and Measurement. London: Palgrave. pp. 167–192.

- Eaton, Lisa (2019). "A simplified approach to measuring national gender inequality". PLOS ONE. 14 (1): e0205349. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1405349S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205349. PMC 6317789. PMID 30605478.