Maryland Bridge

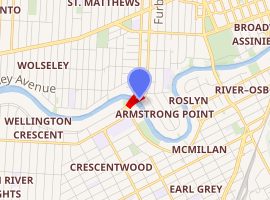

The Maryland Bridge is a bridge that crosses over the Assiniboine River in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It serves as a major transportation route for Winnipeg. The bridge connects Academy Road with Maryland Street and Sherbrook Street. The current structure is the third bridge to span this section of the river. All three bridges were called the Maryland Bridge. Nearby landmarks include Misericordia Health Centre, Cornish Library, and Shaare Zedek Synagogue.

Maryland Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | |

| Carries | |

| Crosses | Assiniboine River |

| Locale | Winnipeg, Manitoba |

| Maintained by | City of Winnipeg |

| History | |

| Construction end | 1969 (southbound side) 1970 (northbound side) |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 25,400 per day (2013) |

| |

History

Original bridge (1894-1921)

The first Maryland Bridge was constructed in 1894 and nicknamed the Boundary Bridge, because Maryland Street once served as Winnipeg's western boundary.[1] In 1915, the city of Winnipeg proposed transforming the bridge into a war memorial though the bridge was decommissioned before this idea came to fruition.[2]

Street car service on the first Maryland Bridge was suspended in June 1920.[3] The bridge previously serviced street car routes 35 and 37.[4] Around the same time, concerns were raised of the safety of the bridge's infrastructure and a ban was put in place on heavy traffic and street cars crossing the bridge.[5] The original Maryland Bridge was decommissioned in 1921 after the completion of construction on the second bridge.[6][7]

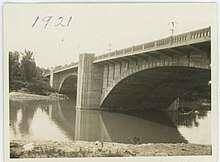

Second bridge (1921-1969)

After a Census of Traffic was conducted on the original bridge because of increased traffic and safety concerns, construction began on the second Maryland Bridge in 1920,[1] and was completed in 1921. In 1951, construction was completed on the Maryland Bridge Cut-Off, a project to cut down on congestion by allowing drivers to turn right off the bridge onto Wellington Crescent without having to wait for a green light.[8]

In 1923, D. L. Saberton committed suicide by jumping from the Maryland Bridge and was the second person to die jumping from the bridge that week.[9] An unnamed man also committed suicide jumping from the bridge in 1925.[10][11]

The bridge was closed for demolition in 1969 upon the opening of the Twin Bridge's western span. The second bridge is memorialized by the Maryland Twin Bridge Monument, located south of the current Maryland Bridge.[12] The monument consists of a corner post shaped as a cairn that was preserved from the second Maryland Bridge.[13]

Current bridge (1969-present)

The current iteration of the Maryland Bridge was opened to traffic in two stages. The west structure on 8 November 1969 and the east structure on 5 August 1970. It was financed by the provincial government and constructed by the Metropolitan Corporation of Greater Winnipeg.[13] In 2013, the Maryland Bridge was the 13th busiest bridge, out of 15, in Winnipeg with an average of 25,400 cars driving over the bridge per day.[14]

The Maryland Bridge was part of the route of the first Manitoba Marathon in 1979, though it is no longer on the marathon route.[15]

Since 1995, the Maryland Bridge has been the site of the Misericordia Health Centre Foundation’s annual Angel Squad fundraiser. As part of the fundraiser, volunteers line the bridge in the early morning dressed as angels offering coffee to drivers in exchange for donations.[16] In 2015, the Angel Squad beat the Guinness World Record for the largest gathering of angels.[17]

In 2007, Doug Prysiazniuk was killed while performing maintenance on the bridge. Prysiazniuk's death delayed bridge maintenance and was ultimately declared an accident.[18]

The space underneath the Maryland Bridge has regularly been a shelter for Winnipeg's homeless. In May 2019, police ordered those living beneath the bridge to leave.[19] Homeless individuals later returned to the bridge despite police orders to dismantle camps. In October 2019, a fire broke out beneath the bridge, though it caused no structural damage to the bridge and left behind no injuries.[20] In the spring of 2020, the city of Winnipeg began testing noise makers to deter homeless camps underneath the bridge. The project was discontinued in June after criticism from city councillors and citizens about the rights and dignity of the homeless population.[21][22]

Architecture

Original bridge

The first bridge was made of steel truss.[13] This iteration of the Maryland Bridge was described by the Winnipeg Free Press as having a "Renaissance character" with "classic mouldings and features".[23]

Second bridge

The second bridge was a concrete arch structure that included a coloured aggregate of red granite, crushed to pass through a .75 inches (19 mm) screen, exposed by scrubbing with steel brushes, and cleaned by several washings of muriatic acid and water.[24]

Current bridge

The current bridge consists of I-shaped AASHTO girders[25] and twin, five-span continuous precast prestressed concrete structures.[26] Renovations to the northbound span occurred in 2005. In 2006, the southbound span was renovated.[1] The bridge has a protected bike lane that continues onto Sherbrooke Street.[27]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maryland Bridge. |

- "Maryland Bridge". Pathways to Winnipeg History. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- "Three New Bridges to Span Assiniboine". Winnipeg Free Press. 12 June 1915. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Maryland Bridge is Closed to Street Cars". Winnipeg Free Press. 1 July 1920. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Darragh, Brian K. (2015). The Streetcars of Winnipeg - Our Forgotten Heritage: Out of Sight - Out of Mind. FriesenPress. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-4602-4654-2. Retrieved 31 May 2020 – via Google Books.

- "Ashdown Says Maryland Street Bridge Is Disgraceful". Winnipeg Free Press. 14 April 1920. p. 9. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "New Maryland Bridge Soon Ready For Traffic". Winnipeg Free Press. 3 August 1921. p. 7. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Maryland Bridge Unlikely to be Rebuilt Before Winter". Winnipeg Free Press. 5 July 1920. p. 5. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "New Maryland Bridge Cut-Off Ready Soon". Winnipeg Free Press. 20 July 1951. p. 3. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "River Takes Life Despite Gallant Rescue Effort". Winnipeg Tribune. 18 September 1923. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Police Think Suicide Was Mysterious Vag". Winnipeg Tribune. 16 October 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "No Clue to Identity of Suicide is Found". Winnipeg Free Press. 17 October 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Perry, Gail (6 June 2016). "How Wolseley remains unabridged". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Goldsborough, Gordon (28 December 2010). "Historic Sites of Manitoba: Maryland Twin Bridge". The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Taylor, Derek (11 July 2013). "Which Winnipeg bridge is the busiest?". Global News. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Morgan, T. Kent (4 June 2018). "40 years of Manitoba Marathons". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Hirschfield, Kevin (4 December 2017). "Angels are gathering at the Maryland Bridge in Winnipeg". Global News. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Dangerfield, Katie (1 December 2016). "Angels gather over the Maryland Bridge". Global News.

- "Fatal accident delays bridge work in Winnipeg". CBC News. 26 September 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Kahn, Ahmar (7 May 2019). "Homeless camp cleared by police, but the problem isn't going away: city councillor". CBC News. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Homeless residents 'heartbroken' after fire ravages Winnipeg camp". CBC News. 2 October 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Keele, Jeff (24 June 2020). "City of Winnipeg to discontinue controversial noise project". CTV Winnipeg. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Froese, Ian (24 June 2020). "Winnipeg silences piercing homeless deterrents under bridges after loud criticism". CBC News. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Three New Bridges to Span Assiniboine". Winnipeg Free Press. 12 June 1915. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

Maryland bridge is given the Renaissance character by its classic mouldings and features.

- Engineering and contracting. Gillette Publishing Co. 1922. pp. 4–. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Rizkalla, S. H.; Nanni, Antonio (2003). Field applications of FRP reinforcement: case studies. American Concrete Institute. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-87031-121-5. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- "Field Demonstration Projects Manitoba". ISIS Canada Research Network. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Marcoux, Jacques (19 September 2016). "Winnipeg's most dangerous intersections for cyclists". CBC News. Retrieved 31 May 2020.