Mary Buckland

Mary Morland Buckland (20 November 1797 – 30 November 1857)[1] was an English palaeontologist, marine biologist and scientific illustrator.[2]

Mary Buckland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 November 1797 Abingdon-on-Thames, Berkshire, England |

| Died | 30 November 1857 (aged 60) Islip, Oxfordshire, England |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Paleontology |

Early life and family

Buckland was born in 1797 in Sheepstead House, Abingdon-on-Thames, to Benjamin Morland,[3] a solicitor,[4] Her mother, Harriet Baster Morland, died when she was a baby, and her father remarried, producing a large family of half-brothers and sisters. She was educated in Southampton, and spent a part of her childhood under the care of Sir Christopher Pegge, a Regius Professor of Anatomy in Oxford, who along with his wife supported her scientific interests. [5]

In the midst of her teenage years she was intrigued by the studies conducted by Georges Cuvier and provided him with specimens, and illustrations.[5] Buckland established a name for herself as a scientific draughtswoman, who helped Conybeare, Cuvier and soon to be husband, William Buckland. [6]

Marriage

According to Caroline Fox, Buckland met her husband William Buckland in the following way:

Both were travelling in Dorsetshire and each were reading a new and weighty tome by the French naturalist Georges Cuvier. They got into conversation, the drift of which was so peculiar that Dr. Buckland exclaimed, "You must be Miss Morland, to whom I am about to deliver a letter of introduction." He was right, and she soon became Mrs Buckland..[7]

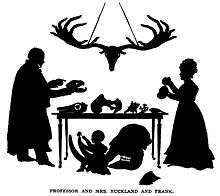

In 1825[3] Mary married Buckland, who later became Dean of Westminster. Their honeymoon was a geological tour lasting a year, including visits to geologists and geological locations across Europe.[8] They had nine children, including Frank Buckland and author Elizabeth Oke Buckland Gordon. The children were exposed to their parents' collections of fossils from an early age and at the age of 4, Frank could successfully identify the vertebrae of an ichthyosaurus.[9] Buckland supported her husband's pursuits, while balancing her time to help educate, and teach her children.[10] She also spent her time promoting education within the villages.[10] During her marriage, her desire to pursue science was limited because of her husband's disproval of women being engaged in scientific pursuits. [6]

Her eldest son Frank, said the following about his mother for her contribution to Buckland's work:

Not only was she a pious, amiable, and excellent helpmate to my father; but being naturally endowed with great mental powers, habits of perseverance and order, tempered by excellent judgement, she materially assisted her husband in his literary labours, and often gave to them a polish which added not a little to their merit … Not only with her pen did she render material assistance, but her natural talent in the use of her pencil enabled her to give accurate illustrations and finished drawings … She was also particularly clever and neat in mending broken fossils … It was her occupation also to label the specimens.[11]

Later Life

In 1842 Mary's husband fell ill and his mental health began to decline and was sent to John Bush's Mental Asylum at Chapham in London[12] . Shortly after, Mary retired to St. Leonard's- on Sea, and continued to show an appreciation of her husband's studies. [13] Mary died in Leonards, Sussex, and was buried in Islip, Oxfordshire [12] Mary Buckland amassed a vast collection of fossils and other specimens and taught in a village school in Islip, near the family's country home, where she died in on 30 November 1857.[6]

Career

Mary Buckland started her career as a teenager producing illustrations and providing specimens for George Cuvier, widely regarded as the founder of paleontology, as well as for the British geologist William Conybeare.[14] She made models of fossils, and labelled fossils for the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, studied marine zoophytes and repaired broken fossils inline with her husband's instructions.

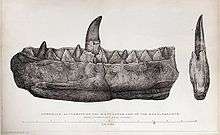

Mary Buckland assisted her husband greatly by writing as he dictated, editing, producing elaborate illustrations for his books, taking notes of his observations, and writing much of it herself.[12] Her skills as an artist are on display in Mr. Buckland's largely illustrated work Reliquiae diluvianae, published in 1823, and in his Geology and Mineralogy in 1836.[12] Her son noted that she was particularly "neat and clever in mending fossils" with specially developed cementing, and in assisting William Buckland's experiments to reproduce fossil tracks and many others.[12] She assisted him when he was commissioned to contribute a volume to The Bridgewater Treatises.

Although Mary Buckland was in poor health after her husband's death, she continued her husband's work and branched out her own research. Examining micro forms of marine life through a microscope, with her daughter Carolin,[14] and arranging a large collection of zoophytes and sponges, which she collected during her visits to the Channel islands of Guernsey and Sark with her husband.[12] Much of her fossil reconstructions are held by the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.[13]

References

- Frith, Uta (7 February 2011). "Females, Fossils and Hyenas – part 1". Blogs: The repository. The Royal Society. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Burek, C. V. (2002). "Where are the Women in Science? A case study using women in the history of geology to develop a European curriculum" (PDF). In Gonzales, M. H. (ed.). Proyecto Penelope – The role of the history of science in secondary education. Tenerife, Spain: Fundación Canaria Orotava de Historia de La Ciencia. pp. 214–221. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- Ogilvie, Marilyn Bailey (1986). "Buckland, Mary Morland". Women in science : antiquity through the nineteenth century : a biographical dictionary with annotated bibliography (4th print. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780262650380.

- Frith, Uta (11 February 2011). "Females, Fossils and Hyenas – part 2". Blogs: The repository. The Royal Society. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- AAAHS and contributors. “Mary Buckland, Nee Morland.” Abingdon-on-Thames, 2015.

- Burek, Cynthia V., and B. Higgs. The Role of Women in the History of Geology. Geological Society, 2007.

- Gordon, Elizabeth (1894). The life and Correspondence of William Buckland. London: John Murray. pp. 91.

- "William Buckland" (PDF). Learning more. Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Bompas, George Cox (1909). Life of Frank Buckland. London: Thomas Nelson. p. 13.

- Buckland, William, and David Knight. Geology and Mineralogy, Considered with Reference to Natural Theology, Volume 1. Published in Association with the Natural History Museum by Routledge, 2003.

- Burek, Cynthia V., and B. Higgs. The Role of Women in the History of Geology. Geological Society, 2007.

- Torrens, H. S. "Buckland [née Morland], Mary (1797–1857), geological artist and curator." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 03, 2008. Oxford University Press,. Date of access 7 Feb.

- Buckland, William, and David Knight. Geology and Mineralogy, Considered with Reference to Natural Theology, Volume 1. Published in Association with the Natural History Museum by Routledge, 2003.

- "Mary Buckland, nee Morland | Abingdon-on-Thames". www.abingdon.gov.uk. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

Further reading

- Torrens, H.S. (2004). "Buckland (née Morland), Mary". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/46486. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mary Buckland. |