Marungu highlands

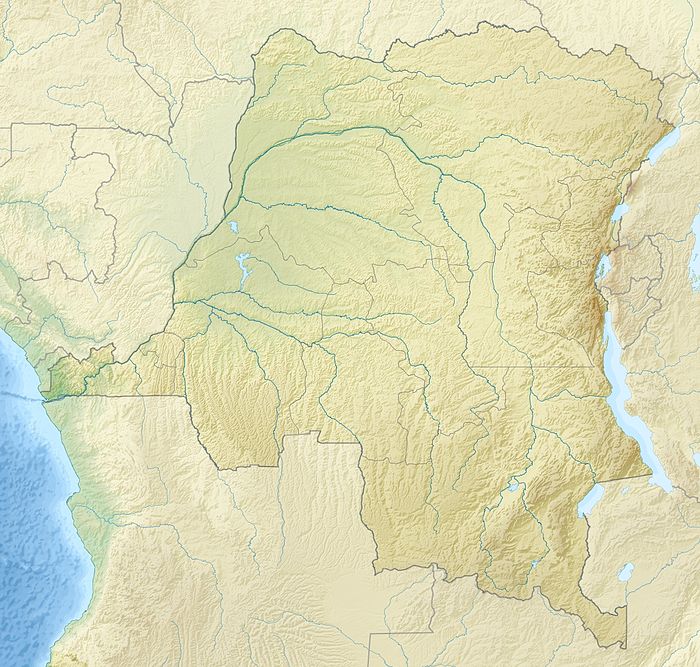

The Marungu highlands are in the Katanga Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the west of the southern half of Lake Tanganyika.

| Marungu highlands | |

|---|---|

Marungu highlands | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,460 m (8,070 ft) |

| Coordinates | 7.131554°S 29.694672°E |

Location

The highlands are divided by the Mulobozi River, which flow into the lake just north of Moba port. The northern section reaches an altitude of 2,100 metres (6,900 ft) while the larger southern part reaches 2,460 metres (8,070 ft). Mean annual rainfall is around 1,200 millimetres (47 in), mostly falling between October and April.[1] The soil is relatively low in nutrients.[1]

A sublacustrine swell extends from the Marungu plateau under the southern basin of Lake Tanganyika, subdividing it into the Albertville and Zongwe basins. The Zongwe trough holds the deepest part of the lake, at 1,470 metres (4,820 ft) below the present lake level. Alluvial cones from the rivers that drain the Marungu Plateau are present at the foot of the Zongwe trough, and there are many V-shaped valleys below the lake level. These features indicate that during the Quaternary (2.588 million years ago to the present) the lake level varied greatly, at times being much lower than now.[2]

The explorer Henry Morton Stanley noted this feature when he visited the region in his journey of 1874–77. He wrote, "Kirungwé Point appears to be a lofty swelling ridge, cut straight through to an unknown depth. There are grounds to believe that this ridge was once a prolongation of the plateau of Marungu, as the rocks are of the same type, and both sides of the lake show similar results of a sudden subsidence without disturbance of the strata."[3]

Ecology

The higher parts of the highlands are Miombo woodland savannas, with scrub plants on the slopes and some dense forest in the ravines, and remains of riparian forest along the streams. Forest plants include Parinari excelsa, Teclea nobilis, Polyscias fulva, Ficus storthophylla and Turrea holstii in ravines, and Syzygium cordatum, Ficalhoa laurifolia and Ilex mitis by the water.[1]

Hyperolius nasicus is a small, slender tree frog with a markedly pointed snout, a very poorly known member of the controversial Hyperolius nasutus group. It is known only from its type locality in the Marungu highlands at Kasiki, at 2,300 metres (7,500 ft).[4] The greater double-collared sunbird (Cinnyris prigoginei) is found only in the riparian forest of this area.[1] The sunbird is found in only a few areas of riparian forest. It has been recorded from Kasiki, the Lufoko River, Matafali, Pande and Sambwe.[5] It is one of 25 bird species in Zaire (out of 1,086 in total) that were considered threatened in 1990.[6]

A 1990 book recommended conservation measures in the Highlands focusing on endemic plants.[7] The Marungu Highlands riparian forest patches are in great danger of destruction from logging and from stream bank erosion by cattle.

There have been proposals to conserve the forests that border the Mulobozi River and Lufuko River above 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) within nature preserves.[1]

Early reports

Prehistoric stone tools, facies with rare bifaces, have been found in the region dating from the Early Pleistocene (over 780,000 years ago) to the present Holocene epoch. During that period the climate alternated several times between arid or semi-arid and pluvial.[8]

The English explorer Richard Francis Burton visited the region in 1857–59. At that time Marungu was one of the sources of slaves collected by the Arabs and taken to the great slave market at Ujiji.[9] The Watuta had earlier plundered the land and almost wiped out the cattle of the inhabitants.[10] A merchant from Oman who had lived in the region for five months told Burton it was divided into three distinct provinces. There were Marungu to the north, Karungu in the center and Urungu in the south. Burton also heard of a Western Marungu, divided from the eastern by the Runangwa River. Burton was somewhat skeptical about the name, which he thought was more likely that of a race than a country.[11] Burton reported that,

The people of Marungu are called Wámbozwá by the Arabs; they are subject to no king, but live under local rulers, and are ever at war with their neighbours. They are a dark and plain, a wild and uncomely race. Amongst these people is observed a custom which connects them with the Wangindo, Wahiao, and the slave races dwelling inland from Kilwa. They pierce the upper lip and gradually enlarge the aperture till the end projects in a kind of bill beyond the nose and chin, giving to the countenance a peculiar duck-like appearance. The Arabs, who abhor this hideous vagary of fashion, scarify the sides of the hole and attempt to make the flesh grow by the application of rock-salt. The people of Marungu, however, are little valued as slaves; they are surly and stubborn, exceedingly depraved, and addicted to desertion.[12]

Stanley visited Marungu in 1876. He wrote, "Though the mountains of Marungu are steep, rugged, and craggy, the district is surprisingly populous. Through the chasms and great cañons with which the mountains are sometimes cleft, we saw the summits of other high mountains, fully 2500 feet above the lake, occupied by villages, the inhabitants of which, from the inaccessibility of the position they had selected, were evidently harassed by some more powerful tribes to the westward."[13]

Joseph Thomson visited the region in 1878–80. He reported that there was no head-chief in Marunga, which was divided into three independent chieftainships that sometimes engaged in warfare. From north to south these were called Movu, Songwe and Masensa. The chiefs were Manda, Songwe and Kapampa. The people were "most excitable and suspicious", and Thomson had difficulty in obtaining permission to travel through the country.[14] Thomson wrote:

The people of Marungu are in every respect different from the Waitawa, partaking much of the wild and savage character of the scenery. They are black, sooty savages, with muscular figures, thick everted lips and bridgeless noses. Clothing was for the most part eschewed; and what there was of it was chiefly native-made bark cloth. There was no such thing as imported European cloth, at least among those living in the mountains ... Goat skins, however, are most commonly used, worn simply over the back and shoulders. ... The Marungu keep considerable flocks of sheep and goats, but do not milk the latter. Fowls also are abundant; and as the soil along the river side is usually good, and the rain falls almost incessantly, vegetable food is raised to a large extent.[15] In most respects the existence of these natives must be of a truly miserable character, living as they do among grassy heights 7000 feet above the level of the sea. The soil is cold and clayey; and as the mountains, except when facing the lake, are entirely devoid of trees, fuel can hardly be got, so that they are compelled to eat their food generally uncooked, and they have to warm themselves as best they can. ... In spite of these disadvantages the high mountains of Marungu are the most populous parts I have seen in Africa, probably owing to the fact that they can raise food throughout the entire year."[16]

Thomson said of the terrain, "We had now no gentle undulations and rounded valleys, but savage peaks and precipices, alternating with deep gloomy ravines and glens. Ridge after ridge had to be crossed, rising with precipitous sides, and requiring hands and knees in the ascent. Now we would go up 3000 feet, to descend as far, repeating the process three times a day, and never getting half a mile of moderately good walking ground." He visited during the rainy season, which added to his discomfort.[17] Thomson conceded, "... the savage and awe-inspiring grandeur of the mountain scenery we traversed in Marungu was not without its relief. Here the sun, darting his rays through a rift in the overhanging cloud-bank, would glorify as if with a golden crown some conspicuous peak, or smile upon some pleasant glade; and there glimpses of Tanganyika would be obtained, 2000 feet beneath us, its waters in the distance seeming as calm and undisturbed as the sleep of innocence."[18]

Notes

- Marungu highlands.

- Clark 1969, p. 29.

- Stanley 1890, p. 26.

- Hyperolius nasicus Laurent.

- Mann & Cheke 2010, p. 269.

- Stuart, Adams & Jenkins 1990, p. 227.

- Stuart, Adams & Jenkins 1990, p. 229.

- Giresse 2007, p. 326.

- Burton 1859, p. 221.

- Burton 1859, p. 229.

- Burton 1859, p. 256.

- Burton 1859, p. 258.

- Stanley 1890, p. 32.

- Thomson 1880, p. 308.

- Thomson 1881, pp. 34–35.

- Thomson 1881, p. 35.

- Thomson 1881, p. 32.

- Thomson 1881, p. 34.

Sources

- Burton, Richard F. (1859). "The Lake Regions of Central Equatorial Africa, with Notices of the Lunar Mountains and the Sources of the White Nile; being the results of an Expedition undertaken under the patronage of Her Majesty's Government and the Royal Geographical Society of London, in the years 1857-1859". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: JRGS. Murray. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, J. D. (1969). Kalambo Falls Prehistoric Site. CUP Archive. GGKEY:H4E29783T4E. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Giresse, P. (2007-11-30). Tropical and sub-tropical West Africa - Marine and continental changes during the Late Quaternary. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-055603-1. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Hyperolius nasicus Laurent, 1943". African Amphibians Lifedesk. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- Mann, Clive F.; Cheke, Robert A. (2010-07-30). "Prigogine's double-collared sunbird". Sunbirds: A Guide to the Sunbirds, Flowerpeckers, Spiderhunters and Sugarbirds of the World. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4081-3568-6. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Marungu highlands". Birdlife. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- Stanley, Henry M. (1890). Through the Dark Continent. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-31935-3. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stuart, S. N.; Adams, Richard J.; Jenkins, Martin (1990). Biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa and Its Islands: Conservation, Management, and Sustainable Use. IUCN. p. 227. ISBN 978-2-8317-0021-2. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomson, Joseph (1880). "Progress of the Society's East African Expedition: Journey along the Western Side of Lake Tanganyika". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography. Edward Stanford. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomson, Joseph (1881). To the Central African Lakes and Back: The Narrative of the Royal Geographical Society's East Central African Expedition, 1878-80. Houghton, Mifflin. Retrieved 2015-08-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Dowsett, Robert J.; Prigogine, Alexandre (1974). L'avifaune des monts Marungu. Cercle hydrobiologique de Bruxelles.