Marriage stone

A marriage stone, nuptial stone or lintel stone[1] is usually a stone, rarely wood, lintel carved with the initials, coat of arms, etc. of a newly married couple, usually displaying the date of the marriage. They were very popular until Victorian times, but fell out of general use in the 20th century. Many survive for aesthetic value, particularly where well carved or of historic value. Many are part of or in the grounds of a listed building or in conservation areas.

Purpose

Marriage stones serve as a record of a marriage, the joining together of two families,[3] especially important in aristocratic families and also sometimes practised amongst the newly established and monied middle classes. They were sometimes added to a building which was constructed specifically as the new family home for the married couple, especially when the dowry was large, or were carved into a pre-existing lintel over the main entrance or over a fireplace.[4] The stones also clearly indicated the ownership of the building to onlookers at the time as well as serving as a record for posterity of both marital bliss and often also of social advancement.[5]

Datestones are a subtly different category in that they primarily commemorate the construction of a building rather than record a marriage. They may do both and such symbolism as entwined hearts[6] indicates that they serve to perform both functions. Date stones are far more common than marriage stones and are found on most types of vernacular buildings, indeed they are in vogue again today (2007), partly through the influence of the significance of the 2000 millennium year. Some buildings have both marriage stones and datestones, such as 'The Hill' at Dunlop, which has a date stone on the 'mansion house' and even the gateposts are dated.

Positioning

The stones were placed where they would be easily and frequently seen by visitors, usually on the lintel above the front door of a house, above a fireplace or in a prominent position facing the entrance or in the gardens, such as above a doorway in wall.[7] Many are no longer visible having been covered over in some way such as when older buildings have been extended, porches built, etc. Often the husband's initials were on the left and the wife's were on the right.[8]

Design

Usually carved into stone or sometimes wood, they can be very detailed, with usually only the initials of the married couple, the date of the marriage and sometimes the coat of arms of the two families, just those of the husband and very rarely the combined coats of arms of both families. In some cases the adornment was religious in nature, such as at 'The Hill' farm mansion house (see photograph) or an artistic design simply placed there as an ornamentation. The designs are found cut into the stone or standing proud of the rock face. Originally some of these stones would have been brightly painted and adorned with gilt.[5]

A marriage stone above the door to the Formal Gardens at Robertland House, East Ayrshire. Circa 1930.

A marriage stone above the door to the Formal Gardens at Robertland House, East Ayrshire. Circa 1930.- The marriage stone lintel at 'The Hill' farm, Dunlop, East Ayrshire.

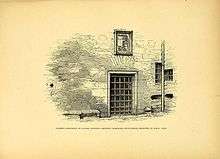

- A view of the marriage stone lintel positioned over the entrance to 'The Hill' farm mansion house together with the motto "Delights and Adorns" and a Bible held in a hand dexter held upright, suggesting both northern Ireland and Protestantism.

A marriage stone set into the old Sawmill near Aiket Castle. The faded markings have been enhanced.

A marriage stone set into the old Sawmill near Aiket Castle. The faded markings have been enhanced. 1811 marriage stone from the original Nettlehirst house near Barrmill, North Ayrshire.

1811 marriage stone from the original Nettlehirst house near Barrmill, North Ayrshire.

Examples

Scotland

- Aiket Castle, Dunlop, East Ayrshire – At Aiket, the stone is set into the wall of a building which was latterly a timber mill is a very worn marriage stone.

- Albion House, Cromarty, Ross and Cromarty – situated in the garden of Albion House and originally from a house which was situated between Albion House and No 49 Church Street (Waterloo House) whose site is now part of the Garden of Albion House. It was demolished in the early 20th century after a fire in the late 19th century but was built by Donald Junor and Katrin (or Katherine) Gally who married in 1710.

- Albion House, Cromarty, Ross and Cromarty – the above-mentioned Donald Junor may be connected to the Andrew or Alexander Junor whose marriage stone was found built into the Courthouse.

- Bogflat, Stewarton, East Ayrshire – now in the Stewarton Museum, the Bogflat stone is dated 1711 with a 'JR' carved into it and the other initials unfortunately cut off.[9]

- Castle of Park, Cornhill, Aberdeenshire – the dining room has an early 18th-century 'marriage stone' set into one wall.

- The Cuff, Gateside, North Ayrshire – M Gibson & I Gibson, 1767.

- Craigdarroch House, Moniave, Dumfries & Galloway – Robert Fergusson, married Lady Janet Cunningham, daughter of the 4th Earl of Glencairn of Maxwelton, in 1537 and their marriage stone, with the shakefork of the Cunninghams, is to be seen at Craigdarroch with the other carved stones on the base of the old tower.

- Fullarton House, Troon – set in a plinth after the house was demolished. Anne Brisbane and William Fullarton 1673.

- The Hill, Dunlop, East Ayrshire – The Hill stone is now placed above an internal window in the original farmhouse, but it, may have been moved or the building substantially altered. It reads '16 ID & BG 92' in old characters ('I' for 'J'). This commemorates the marriage of John Dunlop and Barbara Gilmour of Dunlop cheese fame. A Brown family marriage stone is also present on a lintel entering the old farmhouse.

- The Hill, Dunlop, East Ayrshire – the initials 'AB' and 'JA' positioned over the entrance to The Hill 'mansion house' together with the motto "Delights and Adorns" and a Bible held in a hand held upright, suggesting both Northern Ireland and Protestantism. The 'AB' stands for Andrew Brown, grandson of Barbara and John. He married 'JA', Jean Anderson, daughter of Matthew Anderson of Craighead, which they later inherited. As 'well to do' farmers they may have built the 'mansion house' at 'The Hill', converting the old farm into a dairy and byre, however the window above is 'off centre', suggesting an adaptation.[10]

- Kiktonhall House, West Kilbride. North Ayrshire – built into the back wall of the present building. 'RS MW 1660' with what appears to be 'I S' with an upturned 'V'.

- Knockshinnoch Farm, New Cumnock, East Ayrshire – in the byre, which may be the original farmhouse is a stone with the date 1691 and the initials HD and MC, a heart with what appears to be a dagger in it, a small star and a stags head.

- Lude, Blair Atholl, Pitlochry – the Marriage stone of Alexander Robertson 10th of Lude and Katherine Campbell daughter of Glenorchy.

- Mains of Giffen, Barrmill, North Ayrshire – 'RC MC 1758' on a lintel in the old farm buildings.

- Castle Menzies, Weem, Perthshire – A marriage stone faces the entrance, installed by James Menzies in 1571 to record his 1540 marriage to Barbara Stewart, daughter of John Stewart, 3rd Earl of Atholl and cousin to Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley.[5][11]

- Parkhill House, Dalry – 'JR1732JR', probably the 'Reid' family.

- Robertland House, Dunlop, East Ayrshire – placed above a door leading into the formal gardens.

- Rowallan Castle, Kilmaurs, East Ayrshire. At Rowallan Castle is a stone marked with Jon.Mvr. M.Cvgm. Spvsis 1562.[12]

- Ryefield House, Drakemyre, North Ayrshire – A marriage stone with the date '1786' and the initials 'JK' paired with 'WM' has been incorporated into one wall of the walled garden, presumably originating from an early dwelling house belonging to the Knox family.

- Townhead of Lambroughton, Stewarton, East Ayrshire – a marriage stone is now built into a wall on the farm . It reads 'AL MR 1707'. The 'AL' may stand for Alexander Langmuir. The stone came from a contemporary building which was demolished in the late 20th century.

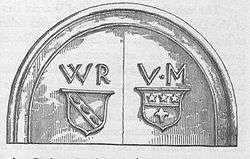

- Woodside House, Parish of Beith – a stone built into the corner of a gable with "G. 1759 R," and "A. 1759 P.". This is for Gavin Ralston of that Ilk, and his spouse Anabella, daughter of James Pollock of Arthurlee. Another has "W.C.P." and "A.C.P." and underneath it are the initials and date, "W. 1845 P.", which is for William Charles Sochran-Patrick and his spouse. Finally, a pediment stone in Roman style has "W.R." and "U.M." for William Ralston of that Ilk, and his spouse, Ursula, daughter of William Muir of Glanderstoun, by Jean, daughter of Mr. Hans Hamilton, Vicar of Dunlop.[13]

Wales

- Penybenglog House, Nevern, South Wales – A wooden lintel used as a marriage 'stone'. Dated 1523, 'WG' & 'RS'.

Ireland

- Killimor castle – the "Marriage Stone" of Teige O'Daly (eldest son of Dermot who died 1614) and Sisily O'Kelly. The stone was returned from Lusmagh (near Cloghan Castle, Co. Offaly) to Killimordaly Churchyard in 1980. The stone was originally inserted above the entrance to Killimor Castle in commemoration of the castle's construction in 1624 where it remained during the various reconstructions of "The Castle" to a more comfortable type of residence during the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Galway City has many fine examples of marriage stones which can be seen all over the city centre both inside buildings and carved on exterior lintels.

Jersey

- Penryn Farm, Bechet es Cats, St. John – marriage stone “1884”.

Modern marriage stones

A two-ton Scottish granite Marriage stone was created for the wedding of Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles, 9 April 2005. Unusually this has carvings on both sides.

Stones associated with marriage

The Treustein

Many synagogues in Germany featured a Treustein, or "marriage stone" at which a goblet was shattered at the culmination of the wedding ceremony.[14]

Hindu weddings

In Hinduism, it is customary in a marriage ceremony for the bride to stand on a stone slab or millstone to symbolise her commitment to the marriage during times of difficulty, in a practice known as Shila Arohan (Ascending the stone).[15]

Holed stones

On the crest of a hill near the village of Doagh in County Antrim, Northern Ireland, sits a Bronze Age standing stone or 'holestone'. It is 1.5 metres high, with a 10 cm diameter hole cut into it. It is not known why the Holestone was created, but has attracted visitors seeking external love and happiness since at least the 18th century. Upon reaching the Holestone couples undertake a traditional ceremony where the woman reaches her hand through the circular hole and her partner takes it, thus pledging themselves to love each other forever. There is a legend regarding a black horse that inhabits the field in which the holestone is situated. According to this legend a young couple were married at the stone, but the groom committed an act of adultery on their wedding night. For this act he was cursed by the stone to spend eternity as a horse, never dying, and never able to leave that field.

See also

- Rock-cut basin – the folklore of holestones.

References

- "Dictionary of the Scots Language". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 381.

- "Galway Civic Trust - Marriage Stones" (PDF). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "Dictionary of the Scots Language". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- McKean, Charles (2001). The Scottish Chateau. The Country house of Renaissance Scotland. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2323-7. p. 12.

- "Dictionary of the Scots Language". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "Dictionary of the Scots Language". Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- "Galway Civic Trust - Marriage Stones" (PDF). Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- MacDonald, Ian (2006). Oral communication to Griffith, Roger S. Ll.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 98 & 99.

- Way, George and Squire, Romily. (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. (Foreword by The Rt Hon. The Earl of Elgin KT, Convenor, The Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). pp. 272–273.

- Dobie, James. (1876) Cuninghame Topographized by Timothy Pont. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. Facing P. 366.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 381.

- Michael Kaufman, Ritual and Custom - Chuppah, My Jewish learning

- Paul Gwynne (7 September 2011). World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. pp. RA5–PT49. ISBN 978-1-4443-6005-9.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marriage stones. |