Markov number

A Markov number or Markoff number is a positive integer x, y or z that is part of a solution to the Markov Diophantine equation

studied by Andrey Markoff (1879, 1880).

The first few Markov numbers are

appearing as coordinates of the Markov triples

- (1, 1, 1), (1, 1, 2), (1, 2, 5), (1, 5, 13), (2, 5, 29), (1, 13, 34), (1, 34, 89), (2, 29, 169), (5, 13, 194), (1, 89, 233), (5, 29, 433), (1, 233, 610), (2, 169, 985), (13, 34, 1325), etc.

There are infinitely many Markov numbers and Markov triples.

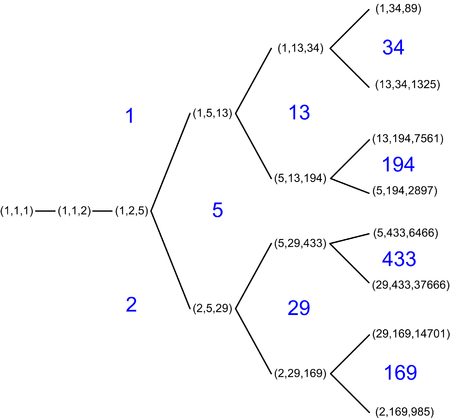

Markov tree

There are two simple ways to obtain a new Markov triple from an old one (x, y, z). First, one may permute the 3 numbers x,y,z, so in particular one can normalize the triples so that x ≤ y ≤ z. Second, if (x, y, z) is a Markov triple then by Vieta jumping so is (x, y, 3xy − z). Applying this operation twice returns the same triple one started with. Joining each normalized Markov triple to the 1, 2, or 3 normalized triples one can obtain from this gives a graph starting from (1,1,1) as in the diagram. This graph is connected; in other words every Markov triple can be connected to (1,1,1) by a sequence of these operations.[1] If we start, as an example, with (1, 5, 13) we get its three neighbors (5, 13, 194), (1, 13, 34) and (1, 2, 5) in the Markov tree if z is set to 1, 5 and 13, respectively. For instance, starting with (1, 1, 2) and trading y and z before each iteration of the transform lists Markov triples with Fibonacci numbers. Starting with that same triplet and trading x and z before each iteration gives the triples with Pell numbers.

All the Markov numbers on the regions adjacent to 2's region are odd-indexed Pell numbers (or numbers n such that 2n2 − 1 is a square, OEIS: A001653), and all the Markov numbers on the regions adjacent to 1's region are odd-indexed Fibonacci numbers (OEIS: A001519). Thus, there are infinitely many Markov triples of the form

where Fx is the xth Fibonacci number. Likewise, there are infinitely many Markov triples of the form

where Px is the xth Pell number.[2]

Other properties

Aside from the two smallest singular triples (1,1,1) and (1,1,2), every Markov triple consists of three distinct integers.[3]

The unicity conjecture states that for a given Markov number c, there is exactly one normalized solution having c as its largest element: proofs of this conjecture have been claimed but none seems to be correct.[4]

Odd Markov numbers are 1 more than multiples of 4, while even Markov numbers are 2 more than multiples of 32.[5]

In his 1982 paper, Don Zagier conjectured that the nth Markov number is asymptotically given by

Moreover, he pointed out that , an approximation of the original Diophantine equation, is equivalent to with f(t) = arcosh(3t/2).[6] The conjecture was proved by Greg McShane and Igor Rivin in 1995 using techniques from hyperbolic geometry.[7]

The nth Lagrange number can be calculated from the nth Markov number with the formula

The Markov numbers are sums of (non-unique) pairs of squares.

Markov's theorem

Markoff (1879, 1880) showed that if

is an indefinite binary quadratic form with real coefficients and discriminant , then there are integers x, y for which f takes a nonzero value of absolute value at most

unless f is a Markov form:[8] a constant times a form

such that

where (p, q, r) is a Markov triple.

There is also a Markov theorem in topology, named after the son of Andrey Markov, Andrei Andreevich Markov.[9]

Matrices

Let Tr denote the trace function over matrices. If X and Y are in SL2(ℂ), then

so that if Tr(X⋅Y⋅X−1 ⋅ Y−1) = −2 then

- Tr(X) Tr(Y) Tr(X⋅Y) = Tr(X)2 + Tr(Y)2 + Tr(X⋅Y)2

In particular if X and Y also have integer entries then Tr(X)/3, Tr(Y)/3, and Tr(X⋅Y)/3 are a Markov triple. If X⋅Y⋅Z = 1 then Tr(X⋅Y) = Tr(Z), so more symmetrically if X, Y, and Z are in SL2(ℤ) with X⋅Y⋅Z = 1 and the commutator of two of them has trace −2, then their traces/3 are a Markov triple.[10]

See also

Notes

- Cassels (1957) p.28

- OEIS: A030452 lists Markov numbers that appear in solutions where one of the other two terms is 5.

- Cassels (1957) p.27

- Guy (2004) p.263

- Zhang, Ying (2007). "Congruence and Uniqueness of Certain Markov Numbers". Acta Arithmetica. 128 (3): 295–301. arXiv:math/0612620. Bibcode:2007AcAri.128..295Z. doi:10.4064/aa128-3-7. MR 2313995.

- Zagier, Don B. (1982). "On the Number of Markoff Numbers Below a Given Bound". Mathematics of Computation. 160 (160): 709–723. doi:10.2307/2007348. JSTOR 2007348. MR 0669663.

- Greg McShane; Igor Rivin (1995). "Simple curves on hyperbolic tori". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série I. 320 (12).

- Cassels (1957) p.39

- Louis H. Kauffman, Knots and Physics, p. 95, ISBN 978-9814383011

- Aigner, Martin (2013), "The Cohn tree", Markov's Theorem and 100 Years of the Uniqueness Conjecture, Springer, pp. 63–77, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00888-2_4, ISBN 978-3-319-00887-5, MR 3098784.

References

- Cassels, J.W.S. (1957). An introduction to Diophantine approximation. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics and Mathematical Physics. 45. Cambridge University Press. Zbl 0077.04801.

- Cusick, Thomas; Flahive, Mari (1989). The Markoff and Lagrange spectra. Math. Surveys and Monographs. 30. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-1531-8. Zbl 0685.10023.

- Guy, Richard K. (2004). Unsolved Problems in Number Theory. Springer-Verlag. pp. 263–265. ISBN 0-387-20860-7. Zbl 1058.11001.

- Malyshev, A.V. (2001) [1994], "Markov spectrum problem", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- Markoff, A. "Sur les formes quadratiques binaires indéfinies". Mathematische Annalen. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. ISSN 0025-5831.

- Markoff, A. (1879). "First memory". Mathematische Annalen. 15 (3–4): 381–406. doi:10.1007/BF02086269.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Markoff, A. (1880). "Second memory". Mathematische Annalen. 17 (3): 379–399. doi:10.1007/BF01446234.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)