Marion Davies

Marion Cecilia Davies (born Marion Cecilia Elizabeth Brooklyn Douras;[1] January 3, 1897 – September 22, 1961) was an American film actress, producer, screenwriter, and philanthropist.

Marion Davies | |

|---|---|

Davies in the 1920s | |

| Born | Marion Cecilia Elizabeth Brooklyn Douras January 3, 1897 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 22, 1961 (aged 64) Hollywood, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hollywood Forever Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Actress, film producer, screenwriter, philanthropist |

| Years active | 1914–1937 |

| Spouse(s) | Horace G. Brown (m.1951) |

| Partner(s) | William Randolph Hearst (1917–1951; his death) |

| Children | Patricia Lake (alleged) |

| Relatives | Rosemary Davies (sister) Reine Davies (sister) Charles Lederer (nephew) Pepi Lederer (niece) |

Davies appeared in several Broadway musicals and one film, Runaway Romany (1917), and then became the mistress of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst. He then took over management of her career. Hearst financed Davies' pictures and promoted her heavily through his newspapers and Hearst Newsreels. He founded Cosmopolitan Pictures to produce her films. Hearst preferred to see her in historical dramas, but her real talent was in comedy. Today Davies is remembered mainly as Hearst's mistress until his death, and as the hostess of many lavish events for the Hollywood elite. In particular, her name is linked with the 1924 scandal aboard Hearst's yacht when one of his guests, film producer Thomas Ince, died.

In the film Citizen Kane (1941), the title character's second wife—an untalented singer whom he tries to promote—was widely assumed to be based on Davies. But many commentators, including Citizen Kane writer/director Orson Welles himself, have defended Davies' record as a gifted actress, to whom Hearst's patronage did more harm than good. She retired from the screen in 1937, choosing to devote herself to Hearst and charitable work.

In Hearst's declining years, Davies provided emotional support until his death in 1951. She married for the first time eleven weeks after his death, a marriage which lasted until Davies died from complications due to malignant osteomyelitis (cancer of the jaw) [2] in 1961 at the age of 64.

Early life

Marion Cecilia Elizabeth Brooklyn Douras was born on January 3, 1897, in Brooklyn, the youngest of five children born to Bernard J. Douras (1857–1935), a lawyer and judge in New York City; and Rose Reilly (1867–1928).[3] Her father performed the civil marriage of Gloria Gould Bishop.[4] She had three older sisters, Ethel, Rose, and Reine.[5] An older brother, Charles, drowned at the age of 15 in 1906. His name was subsequently given to Davies' favorite nephew, screenwriter Charles Lederer, the son of Davies' sister Reine Davies.[6]

The Douras family lived near Prospect Park in Brooklyn. The sisters changed their surname to Davies, which one of them spotted on a real-estate agent's sign in the neighborhood.[7] Even at a time when New York was the melting pot for new immigrants, having a British surname greatly helped one's prospects—the name Davies has Welsh origins.

Educated in a New York convent, Davies left school to pursue a career. She worked as a chorus girl in Broadway revues and modeled for illustrators Harrison Fisher and Howard Chandler Christy. In 1916, Davies was signed on as a featured player in the Ziegfeld Follies.[8]

Career

Early career

After making her screen debut in 1916, modelling gowns by Lady Duff-Gordon in a fashion newsreel, she appeared in her first feature film in the 1917 Runaway Romany.[9] Davies wrote the film, which was directed by her brother-in-law, prominent Broadway producer George W. Lederer. The following year she starred in two films—The Burden of Proof and Cecilia of the Pink Roses. Playing mainly light comic roles, she quickly became a film personality appearing with major male stars, making a small fortune, which enabled her to provide financial assistance for her family and friends.

Hearst and Cosmopolitan Pictures

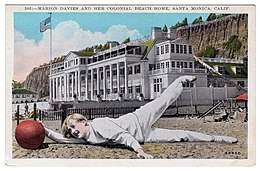

By the mid-1920s, however, Davies' career was often overshadowed by her relationship with William Randolph Hearst and their social life at San Simeon and Ocean House in Santa Monica.[10] The latter was dubbed by Colleen Moore "the biggest house on the beach—the beach between San Diego and Vancouver".

According to her own audio diaries, she met newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst long before she had started working in films.[11] In 1918, Hearst formed Cosmopolitan Pictures and signed Davies to a $5-per-week contract, using his newspapers and Hearst Newsreels to promote her.[12] Hearst's relentless efforts to promote her career had a detrimental effect, but he persisted, making Cosmopolitan's distribution deals first with Paramount, then Goldwyn, and with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Davies herself was more inclined to develop her comic talents alongside her friends at United Artists, but Hearst pointedly discouraged this. Davies, in her published memoirs The Times We Had, concluded that Hearst's over-the-top promotion of her career, in fact, had a negative result. One particular example, he had purchased the Cameo Theatre (located in San Francisco) in 1929. He then lavishly remodeled both the exterior and interior decor in a rosebud-hued Art Moderne motif, and renamed it The Marion Davies Theatre. From Hearst's office windows further up Market Street, he could see pink neon letters constantly spelling out her name above the marquee.[13] Hearst Metrotone Newsreels were included on the program, and these newsreels regularly touted Miss Davies' social activities.

Hearst, who was still married, became romantically involved with Davies, and moved her with her mother and sisters into an elegant Manhattan townhouse at the corner of Riverside Drive and W. 105th Street.[14][15] Cecilia of the Pink Roses in 1918 was her first film backed by Hearst. She was on her way to being the most infamously advertised actress in the world. During the next ten years she appeared in 29 films, an average of almost three films a year.[16] One of her best known roles was as Mary Tudor in When Knighthood Was in Flower (1922), directed by Robert G. Vignola, with whom she collaborated on several films.

The 1922–23 period may have been her most successful, with both When Knighthood Was in Flower and Little Old New York ranking among the top 3 box-office hits of those years. Indeed, she was named the #1 female box-office star by theater owners and crowned as "Queen of the Screen" at their 1924 convention in Hollywood. Other hit silent films included Beverly of Graustark, The Cardboard Lover, Enchantment,The Bride's Play, Lights of Old Broadway, Zander the Great, The Red Mill, Yolanda, Beauty's Worth, and The Restless Sex.

Hearst loved seeing her in expensive costume pictures, but she also appeared in contemporary comedies like Tillie the Toiler, The Fair Co-Ed (both 1927), and especially three directed by King Vidor, Not So Dumb (1930), The Patsy and the backstage-in-Hollywood saga Show People (both 1928). The Patsy contains her imitations, which she usually did for friends, of silent stars Lillian Gish, Mae Murray and Pola Negri. King Vidor saw Davies as a comedic actress instead of the dramatic actress that Hearst wanted her to be. He noticed she was the life of parties and incorporated that into his films.

After seeing photographs of St Donat's Castle in Country Life magazine, the Welsh Vale of Glamorgan property was bought and revitalized by Hearst in 1925 as a gift to Davies.[17] Hearst and Davies spent much of their time entertaining, holding lavish parties with guests at their Beverly Hills estate. Frequent guests included, among others, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and a young John F. Kennedy. Upon visiting St Donat's, George Bernard Shaw was quoted as saying: "This is what God would have built if he had had the money."

Sound films

The coming of sound made Davies nervous because she had a stutter.[16] Her career continued, however, and she made several comedies and musicals during the late 1920s and 1930s, including Marianne (1929), The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (1929), Not So Dumb (1930), The Florodora Girl (1930), The Bachelor Father (1931), Five and Ten (1931) with Leslie Howard, Polly of the Circus (1932) with Clark Gable, Blondie of the Follies (1932), Peg o' My Heart (1933), Going Hollywood (1933) with Bing Crosby, and Operator 13 (1934) with Gary Cooper. She was involved with many aspects of her films and was considered an astute businesswoman. Her career, however, was hampered by Hearst's insistence that she play distinguished, dramatic parts as opposed to the comic roles that were her forte.

Hearst reportedly had tried to push MGM production boss Irving Thalberg to cast Davies in the title role in Marie Antoinette, but Thalberg gave the part to his wife, Norma Shearer. This rejection came on the heels of Davies having been also denied the female lead in The Barretts of Wimpole Street; that role going to Shearer as well. Despite Davies' friendship with the Thalbergs, Hearst reacted by pulling his newspaper support for MGM and moving Davies and Cosmopolitan Pictures distribution to Warner Brothers. Davies' films there were Page Miss Glory (1935), Hearts Divided, Cain and Mabel (both 1936), and Ever Since Eve (1937). Mirroring events at MGM, Warners purchased the rights to the play Tovarich for Davies, but the film version Tovarich was given to Claudette Colbert. Hearst shopped Davies and Cosmopolitan for another year, but no deals were made, and the actress officially retired. In 1943, Davies was offered the role of Mrs. Brown in Claudia, but Hearst dissuaded her from taking a supporting role and tarnishing her starring career. In her 45 feature films, over a 20-year period, Davies had never been anything but the star and always got first billing. The only exceptions were films in which she appeared as herself, and uncredited cameo appearances.

When Cosmopolitan folded, Davies left the film business and retreated to San Simeon. Davies would later state in her autobiography that after many years of work she had had enough and decided to devote herself to being Hearst's "companion and confidante". In truth, she was intensely ambitious, but faced the harsh reality that at the age of forty, she could no longer play the young heroines or madcaps as in earlier films, and that she was unwilling to play supporting roles. Decades after Davies' retirement and death, however, the consensus among some critics is more appreciative of her efforts, particularly in the field of comedy.

Critical reassessment

Due ostensibly to damage done to her reputation by Citizen Kane, Davies has been largely ignored by film critics and historians. But a recent reassessment of her work has come about via broadcast of her films on Turner Classic Movies and the release on DVD of her silent films like When Knighthood Was in Flower, Beauty's Worth, The Bride's Play, Enchantment, The Restless Sex, April Folly, and Buried Treasure. This new availability, along with the publication of The Silent Films of Marion Davies by Edward Lorusso have allowed for a better assessment of Davies' work as an actress. Despite the legend, most of Davies's films made money and she remained a popular star for most of her career. Indeed, Davies was the #1 female box office star of 1922–23 thanks to the enormous popularity of When Knighthood Was in Flower and Little Old New York, which both ranked among the biggest box-office films of 1922 and 1923, respectively.[18]

Personal life

Relationship with William Randolph Hearst

Publishing mogul William Randolph Hearst and Davies lived as a couple for decades but were never married, as Hearst's wife refused to give him a divorce. At one point, he reportedly came close to marrying Davies, but decided his wife's settlement demands were too high. Hearst was extremely jealous and possessive of her, even though he was married throughout their relationship. Lita Grey, the second wife of Charlie Chaplin, wrote four decades later that Davies confided with her about the relationship with Hearst. Grey quoted Davies saying:

God, I'd give everything I have to marry that silly old man. Not for the money and security—he's given me more than I'll ever need. Not because he's such cozy company, either. Most times, when he starts jawing, he bores me stiff. And certainly not because he's so wonderful behind the barn. Why, I could find a million better lays any Wednesday. No, you know what he gives me, sugar? He gives me the feeling I'm worth something to him. A whole lot of what we have, or don't have, I don't like. He's got a wife who'll never give him a divorce. She knows about me, but it's still understood that when she decides to go to the ranch for a week or a weekend, I've got to vamoose. And he snores, and he can be petty, and has sons about as old as me. But he's kind and he's good to me, and I'd never walk out on him.[19]

By the late 1930s, Hearst was suffering financial reversals.[20] After selling many of the contents of St Donat's Castle, Davies sold her jewelry, stocks and bonds and wrote a check for $1 million to Hearst to save him from bankruptcy.[21] Davies had developed a drinking problem over the course of many years, but her alcoholism grew worse in the latter 1930s and the 1940s, as she and Hearst lived an increasingly isolated life. The two spent most of the Second World War at Hearst's Northern California estate of Wyntoon, until returning to San Simeon in 1945.[22]

Hearst died on August 14, 1951.[23] In his will, Hearst provided handsomely for Davies, leaving her 170,000 shares of Hearst Corporation stock, in addition to 30,000 he had established for her in a trust fund in 1950. This gave her a controlling interest in the company for a short time, until she chose to relinquish the stock voluntarily to the corporation on October 30, 1951. She retained her original 30,000 shares and an advisory role with the corporation.[22]

Patricia Lake

Since the early 1920s, there has been speculation that Davies and Hearst had a child together some time between 1920 and 1923. The child was rumored to be Patricia Lake (née Van Cleve), who was publicly identified as Davies' niece.[24] On October 3, 1993, Lake died of complications from lung cancer in Indian Wells, California.[25] Ten hours before her death, Lake requested that her son publicly announce that she was not Davies' niece but Davies' biological daughter, whom she had conceived with Hearst. Lake had never commented on her alleged paternity in public, even after Hearst's and Davies' deaths, but did tell her grown children and friends. Lake's claim was published in her death notice, which was published in newspapers.[24]

Lake told her friends and family that Davies became pregnant by Hearst in the early 1920s. As the child was conceived during Hearst's extra-marital affair with Davies and out of wedlock, Hearst sent Davies to Europe to have the child in secret to avoid a public scandal. Hearst later joined Davies in Europe. Lake claimed she was born in a Catholic hospital outside of Paris between 1920 and 1923 (she was unsure of the precise date). Lake was then given to Davies' sister Rose, whose own child had died in infancy, and passed off as Rose and her husband George Van Cleve's daughter. Lake stated that Hearst paid for her schooling and both Davies and Hearst spent considerable time with her. Davies reportedly told Lake of her true parentage when she was 11 years old. Lake said Hearst confirmed that he was her father on her wedding day at age 17 where both Davies and Hearst gave her away.[24][26]

Neither Davies nor Hearst ever publicly addressed the rumors during their lives. Upon news of the story, a spokesman for Hearst Castle only commented that, "It's a very old rumor and a rumor is all it ever was."[27]

Ince scandal

In November 1924, Davies was among those aboard Hearst's luxury yacht Oneida for a weekend party that resulted in the death of film producer Thomas Ince. Rumors have endured since then that Davies had an alleged relationship with fellow-guest Charlie Chaplin, and that Hearst mistook Ince for Chaplin and shot him out of jealousy. There has never been any evidence to support the rumors.

Ince's autopsy showed that he suffered an attack of acute indigestion while aboard the yacht and was escorted off in San Diego by another of the guests, Dr. Daniel Carson Goodman, a Hollywood writer and producer. Ince was put on a train bound for Los Angeles, but was removed from the train at Del Mar when his condition worsened. He was given medical attention by Dr. T. A. Parker and a nurse, Jesse Howard. Ince told them that he had drunk liquor aboard Hearst's yacht. He was taken to his Hollywood home where he died the following day of a heart condition.[28]

Marriage

Eleven weeks and one day after Hearst's death, Davies married Horace Brown on October 31, 1951, in Las Vegas.[29] It was not a happy marriage. Davies filed for divorce twice, but neither was finalized, despite Brown admitting he treated her badly: "I'm a beast," he said. "I took him back. I don't know why," she explained. "I guess because he's standing right beside me, crying. Thank God we all have a sense of humor."[30][31]

Later years

In her later years, Davies was involved with charity work. In 1952, she donated $1.9 million to establish a children's clinic at UCLA which was named for her.[32] The clinic's name was changed to The Mattel Children's Hospital in 1998. Davies also fought childhood diseases through the Marion Davies Foundation.[16]

She suffered a minor stroke in 1956, and later underwent surgery on her jawbone for osteomyelitis. Twelve days after the operation, Davies fell in her hospital room and broke her leg.[33] Davies made her last public appearance on January 10, 1960, on an NBC television special called Hedda Hopper's Hollywood. Joseph P. Kennedy rented Davies' mansion and worked from behind the scenes to secure his son John F. Kennedy's nomination during the 1960 Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles. Not long afterwards, Davies was diagnosed with stomach cancer.

Death

Davies died of stomach cancer on September 22, 1961, in her home in Hollywood, California.[34]

Her funeral at Immaculate Heart of Mary Church in Hollywood was attended by 200 people and many Hollywood celebrities, including Mary Pickford, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Mrs. Clark Gable (Kay Spreckels), and Johnny Weissmuller. She is buried in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery.[35] Davies left an estate estimated at $20 million.[36]

Cultural references

- The rumors of the Thomas Ince scandal were dramatized in the play The Cat's Meow, which was later made into Peter Bogdanovich's 2001 film The Cat's Meow starring Kirsten Dunst as Davies.

- Patty Hearst co-authored a novel with Cordelia Frances Biddle titled Murder at San Simeon (Scribner, 1996), based upon the death of Ince.

- A documentary film Captured on Film: The True Story of Marion Davies (2001) premiered on Turner Classic Movies.[37]

- In 2004, the story of William Randolph Hearst and Davies was made into a musical titled WR and Daisy with book and lyrics by Robert and Phyllis White; music by Glenn Paxton. It was performed in 2004 by Theater West. It was also performed in 2009 and 2010 at the Annenberg Community Beach House in Santa Monica, California, the estate built by Hearst for Davies in the 1920s.

- Kickstarter campaigns have secured DVD releases of When Knighthood Was in Flower, Beauty's Worth, The Bride's Play, Enchantment, The Restless Sex, April Folly, and Buried Treasure all with new music scores.

Portrayals of Davies

Davies was commonly assumed to be the inspiration for the Susan Alexander character portrayed in Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941), which was based loosely on Hearst's life.[38] This led to various portrayals of Davies as a talentless opportunist. In his foreword to Davies' autobiography, The Times We Had (published posthumously in 1975), Welles wrote that his fictional creation bears no resemblance to Davies:

That Susan was Kane's wife and Marion was Hearst's mistress is a difference more important than might be guessed in today's changed climate of opinion. The wife was a puppet and a prisoner; the mistress was never less than a princess. Hearst built more than one castle, and Marion was the hostess in all of them: they were pleasure domes indeed, and the Beautiful People of the day fought for invitations. Xanadu was a lonely fortress, and Susan was quite right to escape from it. The mistress was never one of Hearst's possessions: he was always her suitor, and she was the precious treasure of his heart for more than 30 years, until his last breath of life. Theirs is truly a love story. Love is not the subject of Citizen Kane.[39]

Welles told filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich that Samuel Insull's building of the Chicago Opera House, and business tycoon Harold Fowler McCormick's lavish promotion of the opera career of his second wife, were direct influences on the screenplay for Citizen Kane. "As for Marion," Welles said, "she was an extraordinary woman—nothing like the character Dorothy Comingore played in the movie."[40]

Davies was portrayed by Virginia Madsen in the telefilm The Hearst and Davies Affair (1985) with Robert Mitchum as Hearst. Madsen later became a Davies fan and said that she felt she had inadvertently portrayed her as a stereotype, rather than as a real person.

Davies was portrayed by Heather McNair in Chaplin (1992); by Gretchen Mol in Cradle Will Rock (1999); and by Kirsten Dunst in The Cat's Meow (2001).

Melanie Griffith was nominated for an Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress – Miniseries or a Movie for portraying Davies in RKO 281 in 2000.

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1917 | Runaway Romany | Romany | Silent / Writer / lost film |

| 1918 | Cecilia of the Pink Roses | Cecilia | Silent / Lost film |

| 1918 | The Burden of Proof | Elaine Brooks | Silent / Lost film |

| 1919 | The Belle of New York | Violet Gray | Silent / only 2 reels survive |

| 1919 | Getting Mary Married | Mary Bussard | Silent / DVD / Producer |

| 1919 | The Dark Star | Rue Carew | Silent / Lost film |

| 1919 | The Cinema Murder | Elizabeth Dalston | Silent / Lost film |

| 1920 | April Folly | April Poole | Silent / DVD missing first reel |

| 1920 | The Restless Sex | Stephanie Cleland | Silent / DVD |

| 1921 | Buried Treasure | Pauline Vandermuellen / Lucia | Silent / DVD missing final reel |

| 1921 | Enchantment | Ethel Hoyt | Silent / DVD |

| 1922 | Bride's Play | Enid of Cashel / Aileen Barrett | Silent / DVD |

| 1922 | Beauty's Worth | Prudence Cole | Silent / DVD |

| 1922 | The Young Diana | Diana May | Silent / Lost film |

| 1922 | When Knighthood Was in Flower | Mary Tudor | Silent / DVD / Blu-ray |

| 1922 | A Trip to Paramountown | Herself | Silent / Short subject |

| 1923 | The Pilgrim | Member of the Congregation | Silent / Uncredited |

| 1923 | Adam and Eva | Eva King | Silent / only 1 reel survives |

| 1923 | Little Old New York | Patricia O'Day | Silent / DVD |

| 1924 | Yolanda | Princess Mary / Yolanda | Silent / print survives in Royal Belgian Film Archive, Brussels |

| 1924 | Janice Meredith | Janice Meredith | Silent / DVD |

| 1925 | Zander the Great | Mamie Smith | Silent / DVD |

| 1925 | Lights of Old Broadway | Fely / Anne | Silent / print survives in Library of Congress |

| 1925 | Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ | Crowd Extra in Chariot Race | Silent / Uncredited |

| 1926 | Beverly of Graustark | Beverly Calhoun / Prince Oscar | Silent / print survives in Library of Congress |

| 1927 | The Red Mill | Tina | Silent / DVD /Director: Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle (as William Goodrich) |

| 1927 | Tillie the Toiler | Tillie Jones | Silent / print survives in Eastman House Museum |

| 1927 | The Fair Co-Ed | Marion | Silent / print survives in Library of Congress |

| 1927 | Quality Street | Phoebe Throssel | Silent / Producer/ DVD |

| 1928 | The Patsy | Patricia Harrington | Silent / DVD / Producer |

| 1928 | The Cardboard Lover | Sally | Silent / Producer / print survives in Library of Congress |

| 1928 | Show People | Peggy Pepper / Patricia Pepoire / Herself | Silent / DVD / Producer |

| 1928 | The Five O'Clock Girl | Patricia Brown | Incomplete |

| 1928 | Rosalie | Princess Rosalie Romanikov | Incomplete |

| 1929 | Marianne | Marianne | Silent / Producer (uncredited); silent version co-starring Oscar Shaw |

| 1929 | Marianne | Marianne | DVD / Producer (uncredited); sound version co-starring Lawrence Gray |

| 1929 | The Hollywood Revue of 1929 | Herself | DVD |

| 1930 | Not So Dumb | Dulcinea 'Dulcy' Parker | DVD / Producer |

| 1930 | The Florodora Girl | Daisy Dell | DVD / Producer |

| 1930 | Screen Snapshots Series 9, No. 23 | Herself | Short subject |

| 1931 | Jackie Cooper's Birthday Party | Herself | Short subject |

| 1931 | The Bachelor Father | Antoinette 'Tony' Flagg | DVD / Producer |

| 1931 | Its a Wise Child | Joyce Stanton | print survives in UCLA archive / Producer |

| 1931 | Five and Ten | Jennifer Rarick | DVD / Producer |

| 1931 | The Christmas Party | Herself | Short subject |

| 1932 | Polly of the Circus | Polly Fisher | DVD / Producer |

| 1932 | Blondie of the Follies | Blondie McClune | DVD / Producer |

| 1933 | Peg o' My Heart | Margaret 'Peg' O'Connell | DVD |

| 1933 | Going Hollywood | Sylvia Bruce | DVD |

| 1934 | Operator 13 | Gail Loveless | DVD |

| 1935 | Page Miss Glory | Loretta Dalrymple / Miss Dawn Glory | DVD / Producer |

| 1935 | A Dream Comes True | Herself | Short subject |

| 1935 | Pirate Party on Catalina Isle | Herself | Short subject |

| 1936 | Hearts Divided | Elizabeth "Betsy" Patterson | DVD / Producer |

| 1936 | Cain and Mabel | Mabel O'Dare | DVD |

| 1937 | Ever Since Eve | Miss Marjorie 'Marge' Winton / Sadie Day | DVD |

References

- The name is sometimes spelled "Marion Cecilia Dourvas" in biographies. In her autobiography, it is spelled "Douras," as it appears in the 1900 U.S. Census when they lived in Brooklyn, New York.

- Guiles, Fred (1972). Marion Davies, A Biography. McGraw Hill. p. 372. ISBN 978-0070251144.

- "Died". Time. May 6, 1935. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

Bernard J. Douras, 82, retired New York City magistrate, father of Film Actress Marion Davies and three other daughters; in Beverly Hills, California. His death caused the cancellation of a huge costume party planned at Davies' home in honor of William Randolph Hearst's 72nd birthday.

- "Married". Time. February 17, 1930. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

Gloria Gould Bishop, daughter of Capitalist George Jay Gould; and Walter McFarlane Barker of Chicago; in Manhattan. He was her second husband. They were married in the Domestic Relations Court by Judge Bernard J. Douras, father of cinemactress Marion Davies.

- 1910 United States Federal Census

- Davies, Marion (1975). The Times We Had. Bobbs-Merrill. ISBN 0-672-52112-1.

- Davies, M. (1975). The times we had: Life with William Randolph Hearst. New York: NY: Random House Publishing.

- "Famous Actress-Philanthropist Marion Davies Dies of Cancer". Tri City Herald. September 18, 1961. p. 2. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- "Marion Davies". Golden Silents. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- "Marion Davies – Homes". www.decofilms.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- The Times We Had, by Marion Davies, edited by Pamela Pfau and Kenneth S Marx

- Longworth, Karina (September 24, 2015). "The Mistress, the Magnate, and the Genius". Slate.

- "Esquire Theatre in San Francisco, CA – Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- Alleman, Richard. "Marion Davies Mansion". New York: The Movie Lover's Guide. pp. 359–60.

- "No. 331: Publisher's Mistress". nytimes.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- "Marion Davies". Deco Films. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- Bevan, Nathan (August 3, 2008). "Lydia Hearst is queen of the castle". Wales on Sunday. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- Lorusso, Edward (2017) The Silent Films of Marion Davies, CreateSpace, p. 96.

- Lita Grey Chaplin. My Life With Chaplin, Grove Press (1966) pp. 214–15

- "Hearst Career Full of Drama". The Milwaukee Journal. August 14, 1951. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- "Marion Davies Dies of Cancer". The Miami News. September 23, 1961. p. 7A. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Victoria Kastner (2000). Hearst Castle: The Biography of a Country House. Harry N. Abrams. p. 183.

- "Allowance Asked By Hearst Widow". Spokane Daily Chronicle. August 22, 1951. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Fiore, Faye (October 31, 1993). "Obituary Revives Rumor of Hearst Daughter : Hollywood: Gossips in the 1920s speculated that William Randolph Hearst and mistress Marion Davies had a child. Patricia Lake, long introduced as Davies' niece, asks on death bed that record be set straight". latimes.com. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 1, 2009. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- "Patricia VanCleve Lake". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. October 16, 1993. p. 8B. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Vogel, Michelle (2005). Children of Hollywood: Accounts Of Growing Up As the Sons and Daughters Of Stars. McFarland. pp. 208–09. ISBN 0-7864-2046-4.

- Fiore, Faye (October 31, 1993). "Obituary Revives Rumor of Hearst Daughter : Hollywood: Gossips in the 1920s speculated that William Randolph Hearst and mistress Marion Davies had a child. Patricia Lake, long introduced as Davies' niece, asks on death bed that record be set straight". latimes.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Source: Citizen Hearst by W. A. Swanberg. pp. 445–46. Press hostile to Hearst fueled the rumors. Op cit p. 446 The District Attorney of San Diego, Chester C. Kempley made an inquiry into the events and issued a statement to the effect that he was satisfied that Ince's death was due to "heart failure due to an attack of acute indigestion". Op cit p. 446 The quote is footnoted. The source for Mr. Kempley's statement is given as the New York Times December 4, 1924.

- "Sea Captain wed to Marion Davies. Ex-Actress Protegee of Hearst Married in Surprise Service by Las Vegas Justice. Hearst Kinship Disputed Hearst Agreement Discussed". New York Times. Associated Press. November 1, 1951. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- "Marion Davies Files. Sues Husband for a Divorce. Married Last October". New York Times. July 17, 1952. Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- "New Horizons". Time. July 28, 1952. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- "UCLA: Facts & History". Archived from the original on December 19, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- "Marion Davies, film star of 1920s confidante of Hearst, dies at 64". The Leader-Post. September 23, 1961. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- "Marion Davies Sinking. Actress, 61, Said to Be Near Death, Gets Last Rites". New York Times. United Press International. September 21, 1961.

- "Ex-Actress' Funeral Held". The Spokesman-Review. September 27, 1961. p. 13. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Fleming, E. J. (2005). The Fixers: Eddie Mannix, Howard Strickling And The Mgm Publicity Machine. McFarland. p. 146. ISBN 0-786-42027-8.

- Captured on Film: The True Story of Marion Davies Archived June 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at the Turner Classic Movies Database

- Transcript, The Battle over Citizen Kane Archived December 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine on PBS' American Experience; retrieved January 22, 2012

- Davies, Marion, The Times We Had: Life with William Randolph Hearst; foreword by Orson Welles, May 28, 1975. Indianapolis and New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1975 ISBN 0-672-52112-1

- Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles. New York: HarperCollins Publishers 1992 ISBN 0-06-016616-9 p. 49. Welles states, "The real story of Hearst is quite different from Kane's ... There's all that stuff about McCormick and the opera. I drew a lot from that from my Chicago days. And Samuel Insull."

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marion Davies. |

- Marion Davies on IMDb

- Marion Davies at the Internet Broadway Database

- Marion Davies at the TCM Movie Database

- Photographs of Marion Davies and bibliography

- Large collection of Marion Davies images

- Marion Davies papers, 1915–1928., held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts