Marie de Romieu

Marie de Romieu was a 16th-century French poet from Viviers, France. Although her exact date of birth is unknown, she was most likely born between 1526 and 1545, and died around 1589. Like her origins, most of her life remains a mystery. She is mostly known for her poetic discourse on the superiority of women, as well as an attributed French translation of a work by Italian author Alessandro Piccolomini, which provided behavioral and societal instructions for young ladies and their mothers.

Background

Besides her place of birth, not much else is known about de Romieu; her occupation, education and background vary according to the source. Some sources place her as a noblewoman who frequented the French court, even naming her as a favorite lover of King Henry III.[1]

Family

The biographical information concerning Marie de Romieu is scarce at best. She had a brother, Jacques de Romieu, also a poet, who was her publisher and mentor. French author and archivist Auguste Le Sourd claims the family was composed of bakers in Viviers, although this account is widely disputed due to Marie's level of education.[2] Another theory places both Marie and Jacques in the entourage of their supposed beneficiary, Jean de Chastellier, the finance minister for kings Charles IX and Henry III. In her poems, she mentions a son and the press of certain domestic duties,[2] thus implying that she was married, and had at least one son . Her poems also reveal that she wanted to be a full-time writer and scholar; the preface of her poetic collection states that she wrote it in great haste, because she had no free time due to her household duties.[3]

Education

The only clue into Marie de Romieu's education is found through her body of work, which was heavily influenced by Pierre de Ronsard and classical writers such as Hesiod, Ovid and Virgil. It is speculated that she either learned from her brother Jacques, or at least shared some of his lessons. In 1584, some of her works appear as introductory poems in her brother's poetic anthology, which included Latin translations.[4] Since her poetry included translations of Renaissance Neo-Latin Poets, it can be inferred that she was proficient in Latin, which suggests a higher level of education than most women, and one only attained by those in the elite. She may also have been fluent in Italian due to her translations of Italian authors such as Petrarch. However, her fluency in Italian is not certain, for French translations of the works were available at the time.[2]

Translations

A good part of de Romieu's work consists of translations of works by Classical, Neo-Latin and Italian poets, which was not uncommon during the time period. The translation of classical and humanist texts was widespread during the Renaissance in France, which in turn lead to more women gaining access to more advanced education. Marie de Romieu was part of this trend, as well as other 16th century French women poets, such as Marie de Gournay, Anne de Graville and Madeleine des Roches.[3]

Identity Controversy

Because of the lack of accurate biographical data, there has been some controversy over the veracity of Marie de Romieu's authorship of her Discourse over the superiority of women over men, which appeared in her Les Premières Oeuvres Poétiques (1581), as well of the translation Instruction for Young Women (1572). The Discourse, published by her brother Jacques de Romieu, has been attributed to Jacques himself by some critics.[3] However, according to French poet Guillaume Colletet, Marie's style in her Premières Oeuvres is more refined than that of her brother's, which was “rough and hard” in his own work.[2] In the translation of Instruction for Young Women, the only reference to an author refers to the initials M.D.R., which could belong to her, but also to other French authors of the time besides Marie, such as Madeleine des Roches.[5]

Instructions pour les jeunes dames (1572)

One of the works most widely attributed to Marie de Romieu, Instruction for Young Women, was the French translation of Alessandro Piccolomini’s Dialogo dove si ragiona della bella creanza delle done, dello Stordito accademico Intronato.[6] This particular work, signed solely by the initials M.D.R., appeared in later editions as The Messenger of Love and Instructions to Incite Young Ladies to Love. The premise of the work was to instruct young ladies to lead a virtuous and pure path.[2]

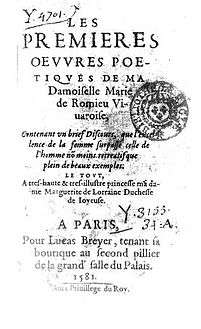

Les Premières Oeuvres Poétiques (1581)

The first work signed by “Marie de Romieu” surfaced in Paris in 1581, titled Les Premières Oeuvres Poétiques de ma Damoiselle Marie de Romieu Vivaroise.[7] A sort of anthology of verse, it contained occasional brief pieces flattering some authority figures in Viviers.[8] Premières Oeuvres features de Romieu's discourse on the superiority of women as its opening piece. The entirety of the work was made up of a mixture of styles common to the Renaissance which included elegies, eclogues, odes, sonnets and hymns.[9]

Brief discours: Que l’excellence de la femme surpasse celle de l’homme

Perhaps the most widely known work associated with Marie de Romieu, her Brief discourse on the superiority of woman over man, was a response to an anti-feminist text penned by her brother, Jacques.[8] Some critics attribute Jacques as the actual author of the Discourse, but this theory has been mostly rejected due to stylistic differences. Featured as the first piece in Premières Oeuvres, de Romieu's discourse on the superiority of women builds itself by praising the courage, wit and virtue of women. It argues that women were visibly more beautiful than their male counterparts because they were a refined product from man, who had been made with clay.[2] In her discourse, de Romieu asserts that women were superior to men in their sacrifices and charity work. She condemns men who fault women for their failings and for leading them astray, claiming they are responsible for their own actions. She also accuses men of trying to deliberately deceive women with ‘fine words’[2] and goes into great detail elaborating the different types of deception perpetrated by men: those who cite God's will and authority, those who pose as protectors of female virtue, or those who pretend to 'serve' women.[10] Furthermore, she illustrates women as the source of learning, both in ancient times and her own. In her conclusion, she reasons that life without women would be lacking in social graces and virtues; she also points out that it is not by accident that the classical virtues are depicted as women.

Besides her focus on the superiority of women, Marie de Romieu discusses the male sex as well. She recognizes "men of courage", "men of knowledge", and the general grandeur of men, but wonders what exactly her society values in such men, such as their courage, their spirit, their magnificence, their honor or their excellence.[11] She also questions if her society values those men due to their virtues or simply due to the fact they were men.[11]

Marie de Romieu's discourse is closely based on part of a 1554 work by Charles Estienne, titled Paradoxes, which are notions contrary to the common opinion. Estienne's work, in turn, was itself based on Paradoxes, a work by Italian humanist author Ortensio Lando. Lando's piece was mainly a list of “exemplary ladies”, while Estienne builds onto that by omitting some Italian names and adding some French ladies to it.[2] De Romieu, however, took it further. She follows Estienne's prose, adding women she thought were deserving of praise. She paid special attention to the role of educated women, especially her contemporary female poets, praising in her Discourse other French female writers, such as Catherine de Clermont, Marguerite de Navarre, and Madeleine and Catherine des Roches.[3] Notably, she removed the names of women who were entirely devoted to serving their husbands, as well as women who attempted to hide their accomplishments from public view.[2]

The greatest difference between de Romieu's Brief Discourse and Estienne's Paradoxes can be found within the author's voice. Marie de Romieu's is distinctly a woman's voice, showcasing true indignity at the idea that it is women who lead men astray. She proceeds to thoroughly develop on the notion that men are at fault, attempting to seduce women with their wily ways. De Romieu then accuses them of blaming guileless women for the seduction they impose upon their innocence.[2] She attributes the injustice to man's ignorance, comparing him to a “cock who cannot distinguish between a pearl and a stone”. Furthermore, while Estienne's audience was primarily masculine, de Romieu speaks to multiple audiences. She addresses women, including herself, as “us, women” and “we, my ladies”, as well as a universal and neutral “one”.[12] She utilizes those when presenting dialogue in which a masculine voice presents arguments that are subsequently countered by her own female voice.

The Querelle des Femmes

Marie de Romieu weighs in in the Querelle des Femmes, or the woman question a generation before early feminists associated with the theme, famously from Lyons, such as Louise Labé and Pernette du Guillet. While she comes to the defense of women, she almost never establishes her own voice on issues such as love, marriage, or life in general, unlike the female poets that came after.[3] She seemed to opt for imitating what she considered the best poetry, regardless of whether it was made by a man or a woman. Differing from Labé, Marie de Romieu's love poems focus firstly on her patron's love for others and, secondly, as a translation exercise.[3] De Romieu does not open up about her own emotions or preferences, other than the importance of education. In a particular sonnet, addressed to her son, she reminds him that the only lasting virtue is knowledge[3]

Bibliography

- Brée, Germaine. Women Writers in France: Variations on a Theme. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1973.

- Charité, Claude La. ""Ce Male Vers Enfant De Ta Verve Femelle": Les Destinataires Féminins De La Lyrique Amoureuse De Marie De Romieu." Nouvelle Revue Du XVIe Siècle 18, no. 2 (2000): 79-92.

- Charité, Claude La. 2011. "How Should Sixteenth-Century Feminine Poetry Be Taught? The Exemplary Case of Marie de Romieu." Teaching French Women Writers of the Renaissance and Reformation, 230-241. New York, NY: Modern Language Association of America, 2011

- Charité, Claude La. "Le Problème De L'attribution De L'instruction Pour Les Jeunes Dames (1572) Et L'énigmatique Cryptonyme M.D.R." Bibliothèque D'Humanisme Et Renaissance 62, no. 1 (2000): 119-28. Accessed April 3, 2016. JSTOR.

- Feugère, Léon. "Marie De Romieu." In Les Femmes Poëtes Au XVIe Siècle, 27-34. Paris: Didier Et Companie, 1860.

- Larsen, Anne R. "Paradox and the Praise of Women: From Ortensio Lando and Charles Estienne to Marie De Romieu." Sixteenth Century Journal 28, no. 3 (1997): 759-74. McFarlane, I. D. Renaissance France, 1470-1589. A Literary History of France. New York: Ernest Benn Limited, 1974.

- Maclean, Ian. Romieu, Marie de (?1545–1590). n.p.: Oxford University Press, 2005. Oxford Reference

- Romieu, Marie de, and Prosper Blanchemain. Oeuvres poétiques de Marie de Romieu. n.p.: Paris : Librairie des Bibliophiles, 1878., 1878

- Rothstein, Marian. "Marie De Romieu." In Writings by Pre-revolutionary French Women: From Marie De France to Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, edited by Anne R. Larsen and Colette H. Winn, 137-49. 1st ed. Vol. 2. New York: Garland Publ., 2000. Sartori, Eva Martin. The Feminist Encyclopedia of French Literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Shapiro, Norman R. "Marie De Romieu." In French Women Poets of Nine Centuries: The Distaff and the Pen, 242-55. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

- Warner, Lyndan. "The Querelle Des Femmes." In The Ideas of Man and Woman in Renaissance France, 93-119. 1st ed. Women and Gender in the Early Modern World. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011.

- Winandy, Andre E. "Marie de Romieu. Les Premieres oeuvres poetiques: Etude et edition critique." Dissertation Abstracts: Section A. Humanities and Social Science 29, (1969): 3163A-3164a.

- Winn, Colette H. Teaching French Women Writers of the Renaissance and Reformation. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2011.

References

- Larsen, Anne (2000). Writings by Pre-Revolutionary French Women. New York: Garland Publishers. pp. 137–149.

- Larsen, Anne (2000). Writings By Pre-Revolutionary Women: From Marie de France to Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. New York: Garland Publishers. pp. 137–149.

- Sartori, Eva (1999). The Feminist Encyclopedia of French Literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Winandy, Andre (1969). Les Prémières Oeuvres Poétiques: étude et edition critique.

- La Charité, Claude (2000). "Le Problème de l'Attribution de l'Instruction Pour Les Jeunes Dames (1572) et l'Énigmatique Cryptomyne M.D.R.". Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance.

- Winandy, Andre (1972). Les Prémières Oeuvres Poétiques: Étude et Edition Critique.

- Winandy, Andre (1972). Prémières Oeuvres Poétiques: Étude et Edition Critique.

- R. Shapiro, Norman (2008). French Women Poets of Nine Centuries: The Distaff and the Pen. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 242–255.

- Feugère, Leon (1860). Les Femmes Poètes au XVIème Siècle. Paris: Didier et Companie. pp. 27–34.

- Warner, Lyndan (2011). The Ideas of Man and Woman in Renaissance France. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 93–104.

- Warner, Lyndan (2011). The Ideas of Man and Woman in Renaissance France. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 93–119.

- Larsen, Anne (2000). Writings By Pre-Revolutionary Women: From Marie de France to Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. NEw York: Garland Publishers. pp. 137–149.