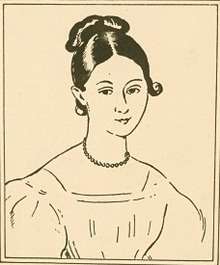

Marie Bigot

Marie Bigot (3 March 1786– 16 September 1820) was a French piano teacher whose full name was Marie Kiéné Bigot de Morogues. As a composer she is best known for her sonatas and études.[1]

Marie Kiéné was born on 3 March 1786 at Colmar[2] in Alsace. After marrying M. Bigot, she moved to Vienna in 1804, where she lived for five years. She was highly accomplished at the keyboard and played for Haydn, who exclaimed, "Oh, my dear child, I did not write this music – it is you who have composed it!" He wrote on the sheet from which she played, "On 20 February 1805, Joseph Haydn was happy." She became a friend of Salieri. Her husband being the librarian of Count Razumovsky, she became friendly with Beethoven, who admired her playing. She was the first to play for him, from the autograph, his newly written Appassionata Sonata,[3] impressing him so much that he told her, "That is not exactly the character I wanted to give this piece; but go right on. If it is not wholly mine it is something better."[4] He gave her the autograph of the Appassionata.[5] In 1808, after a misunderstanding over Beethoven's invitation to take Marie and her three-year-old daughter, Caroline, for a drive and her refusal, the famous composer sent an apologetic letter to her and her husband, writing, "It is one of my foremost principles never to occupy any other relations than those of friendship with the wife of another man. I should never want to fill my heart with distrust towards those who may chance some day to share my fate with me, and thus destroy the loveliest and purest life for myself."[6] The Bigots returned to Paris in 1809. Marie composed, gave lessons, and did much to introduce Beethoven's music to Parisian audiences.[7] In 1812, her husband was taken prisoner as part of Napoleon's campaign in Russia, and Marie took to teaching piano to support her two children.[8] In 1816 she gave lessons to Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn in Paris. She died on 16 September 1820 in Paris, aged 34.[9]

Her Compositions

Marie Bigot studied harmony and composition with Auber and Cherubini in Paris. She composed a Sonata, op. 1 (dedicated to Queen Luise of Prussia), and Andante varié op. 2 (with eight variations and a caprice, dedicated to her sister Caroline Kiéné) while living in Vienna. Then after returning to Paris, she published a Rondeau, and a set of Etudes. Fétis mentions a set of waltzes, and although they are in her hand and ascribed with her name, he doubts that she composed them.[10][11] An article written upon her death at age 34 mentions that she had composed more music, but had refused to publish it "out of modesty."[12]

References

- "Vivace Press". Archived from the original on 2013-03-03. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- http://etienne.biellmann.free.fr/colmar/en/bigota.htm

- Mitchell, Mark Lindsey, Virtuosi: a defense and a (sometimes erotic) celebration of great pianists, Indiana University Press, 2001, p. 159.

- Forbes, Elliot, Thayer's Life of Beethoven, Part 1, Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 412-413.

- Geiringer, Karl, Haydn: a creative life in music, University of California Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0-520-04317-6, p. 184.

- Kalischer, Alfred Christlieb, Beethoven's Letters V1: A Critical Edition, with Explanatory Notes, Kessinger Publishing, LLC (2008)p. 137.

- Elson, Arthur, Woman's Work in Music, (Boston: 1903) BiblioBazaar, 2007, ISBN 1-4346-7444-4, ISBN 978-1-4346-7444-9, p. 118.

- Florence Launay, Les compositrices ed France au XIXe siecle, (Paris: Fayard, 2006), p. 215

- Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed., 1954, Vol. 1, p. 705

- Florence Launay, Les compositrices ed France au XIXe siecle, (Paris: Fayard, 2006), p. 215

- https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/en/artikel/Marie_Bigot.pdf

- Journal des théâtres, de la littérature et des arts, n. 202, Nov. 9, 1820, p. 4.