Mariana de Jesús de Paredes

Mariana of Jesus de Paredes (Spanish: Mariana or María Ana de Jesús de Paredes; October 31, 1618 – May 26, 1645), is a Roman Catholic saint and was the first person to be canonized from what is now Ecuador. She was a recluse who is said to have sacrificed herself for the salvation of her city. She was beatified by Pope Pius IX in 1853 and canonized by Pope Pius XII in 1950. She is the patron saint of Ecuador and venerated at the Church of the Society of Jesus in Quito. Her feast day is celebrated on May 26 by the nation and on May 28 by the Franciscan Order.

Mariana of Jesus de Paredes, T.O.S.F. | |

|---|---|

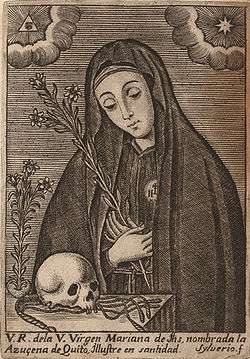

18th-century engraving of Mariana de Jesús by Francisco Sylverio de Sotomayor | |

| Lily of Quito | |

| Born | October 31, 1618 Quito, Royal Audiencia of Quito, Viceroyalty of Peru, Spanish Empire |

| Died | May 26, 1645 (aged 26) Quito, Royal Audiencia of Quito, Viceroyalty of Peru, Spanish Empire |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church (Ecuador & Third Order of St. Francis) |

| Beatified | November 10, 1853, Vatican City by Pope Pius IX |

| Canonized | July 9, 1950, Vatican City by Pope Pius XII |

| Major shrine | Church of the Society of Jesus, Quito, Ecuador |

| Feast | May 26 (May 28 for the Franciscan Order) |

| Attributes | Lily, black cassock embroidered with the Christogram of IHS |

| Patronage | Ecuador; Americas; bodily ills; loss of parents; people rejected by religious orders; sick people; sickness |

Life

She was born Maríana de Paredes Flores y Granobles y Jaramillo in the city of Quito, then part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, on October 31, 1618. Born of aristocratic parents on both sides of her family, her father was Jerónimo de Paredes Flores y Granobles, a nobleman of Toledo, and her mother was Mariana Jaramillo, a descendant of one of the leading conquistadors.[1] Mariana was the youngest of eight children, and it is claimed her birth was accompanied by most unusual phenomena in the heavens, clearly connected with the child and juridically attested at the time of the process of her beatification.[2] Orphaned at the age of four, she was taken in and raised by her older sister, Jerónima de Paredes, and the latter's husband, Cosme de Caso. Drawn to a spiritual life, her sister and brother-in-law allowed her to live in seclusion in their house, leading an ascetical lifestyle, similar to Rose of Lima to whom she is often compared. She refused entry into a monastery, despite urging from her brother-in-law and guardian Cosme de Caso. She subjected herself to bodily mortification, with the aid of her Indian servant. She did not live in total seclusion, but rather centered her spiritual life on the nearby Jesuit church, where she participated in the Sodality of Our Lady, established by the Society in their various churches around the world to help the laity in their desire to deepen their spiritual lives.[3]

It is reported that the fast which Paredes kept was so strict that she took scarcely an ounce of dry bread every eight or ten days. The food which miraculously sustained her life, as in the case of Catherine of Siena and Rose of Lima, was, according to the sworn testimony of many witnesses, the Eucharist alone, which she received every morning at Mass.[2]

Paredes' spiritual life was closely connected to the Jesuits, but, at the suggestion of her spiritual director, she became a member of the Third Order of St. Francis.[4] This was likely advised to her as enrolling in that Order gave her an official status reflective of her penitential way of life in Spanish society, for which the Jesuits had no equivalent. The religious name she assumed at that time, Mariana of Jesus, was no doubt indicative as to where her spiritual heart lay. According to her Jesuit hagiographer, she did not go to the Franciscan church to receive the scapular and rope cincture proclaiming membership in that life, but sent someone else.[5]

Following Paredes' death in 1645, her funeral and burial were held in the Jesuit church. The funeral sermon that the priest Alonso de Rojas preached emphasized her bodily mortification and renunciation of the flesh, and put her forward as a model for females in Quito to emulate. "Learn girls of Quito, from your fellow countrywoman, [to prefer] holiness over beauty, virtues over ostentation."[6] The sermon became a key document in the long process to establish her saintliness, beatification (1853), and final canonization (1950).

The Friars Minor claimed Paredes as a saint of the Franciscan Order. She did wear the Franciscan scapular and cord, but her 17th-century Jesuit hagiographer, Jacinto Morán de Butrón, claims that the Jesuits nurtured her spiritual life. Soon after her death, the Franciscan Province of Peru, based in Lima, included a biography of Mariana in the history of the province, citing the Jesuit funeral sermon as a source.[7]

Paredes possessed an ecstatic gift of prayer and is said to have been able to predict the future, see distant events as if they were passing before her, read the secrets of hearts, cure diseases by a mere sign of the Cross or by sprinkling the sufferer with holy water, and at least once restored a dead person to life.[4] During the 1645 earthquakes and subsequent epidemics in Quito, she publicly offered herself as a victim for the city and died shortly thereafter. It is also reported that, on the day she died, her sanctity was revealed in a wonderful manner: Immediately after her death, a pure white lily sprang up from her blood, blossomed and bloomed, a prodigy which has given her the title of "The Lily of Quito".[2] The Republic of Ecuador has declared her a national heroine.

Canonization

Soon after Paredes' death, at the urging of the Jesuit Fathers, the Bishop of Quito, Alfonso de la Peña y Montenegro, initiated the first preliminary steps towards the canonization of Paredes as well as her niece, Sebastiana de Caso, and instituted the process of inquiring into and collecting evidence for the sanctity of her life, her virtues and her miracles. King Charles II of Spain took up the cause of their canonization, in an effort to promote the connection of native-born colonists in the Americas with the Spanish nation, as well as proving the faith of the colonial population.

The Sacred Congregation of Rites, having discussed and approved of this process, decided in favor of the formal introduction of the cause, and Pope Benedict XIV signed the commission for introducing the cause on December 17, 1757. After the Suppression of the Society of Jesus throughout the Spanish Empire in 1767, the cause for Paredes' canonization was taken over by the Spanish Crown, which appointed a Chilean priest as Postulator of the cause to the Holy See. Her veneration was encouraged in the various Spanish colonies of South America.

The Apostolic process concerning the virtues of Mariana de Paredes was drawn up and examined in due form by the two Preparatory Congregations and by the General Congregation of Rites, and orders were given by Pope Pius VI for the publication of the decree attesting the heroic character of her virtues. The process concerning the two miracles wrought through the intercession of this servant of God was subsequently prepared and was examined and accepted by the three congregations, and formally approved on January 11, 1817, by Pope Pius IX.[4]

The General Congregation having decided in favor of proceeding to the beatification, Pope Pius IX commanded the Brief of beatification to be prepared. Peter Jan Beckx, Superior General of the Society of Jesus, petitioned the cardinal Costantino Patrizi Naro to order the publication of the Brief, and his request was granted. The Brief was read and the solemn beatification took place in the Basilica of St Peter in Rome on November 10, 1853. Many miracles have been claimed to have been the reward of those who have invoked her intercession, especially in America. An additional miracle having been confirmed by the General Congregation, her canonization was approved by Pope Pius XII and celebrated in 1950.

Veneration

Since Parades was beatified, many parishes and educational facilities have been placed under her patronage throughout Latin America. A congregation of teaching Religious Sisters named for her was founded in 1873 by Mercedes de Jesús Molina.

Further reading

- Espinosa Pólit, Aurelio, S.J. Santa Mariana de Jesús, hija de la Compañía de Jesús: estudio histórico-ascético de su espiritualidad. Quito: La Prensa Católica 1956.

- Keyes, Frances Parkinson. The Rose and the Lily. New York: Hawthorn 1961.

- Moncayo de Monge, Germania. Mariana de Jesús, Señora de Indias. Quito: La Prensa Católica 1950.

- Morán de Butrón, Jacinto, S.J. Vida de Santa Mariana de Jesús. Edited by Aurelio Espinosa Pólit, S.J. Quito: Imprenta Municipal 1955. First published in 1732.

- Morgan, Ronald J. "Hagiography in Service of the Patria Chica: The Life of St. Mariana de Jesús, 'Lily of Quito', chapter 5 of Spanish American Saints and the Rhetoric of Identity, 1600-1810. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 2002, pp. 99-117.

- Phelan, John Leddy. The Kingdom of Quito in the Seventeenth Century: Bureaucratic Politics in the Spanish Empire. Madison: University of Wisconsin 1967.

References

- López Molina, Hector. "Santa Mariana de Jesús". Enciclopedia de Quito.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Bl. Mary Anne de Paredes". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- Ronald J. Morgan, Spanish American Saints and the Rhetoric of Identity, 1600-1810. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 2002, pp.102-03.

- "Franciscan-sfo.org". www.franciscan-sfo.org. Archived from the original on 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- Morgan, Spanish American Saints p. 108 quoting Morán de Butrón.

- Rojas Sermón, quoted in Morgan, Spanish American Saints, p. 104.

- Morgan, Spanish American Saints, p. 106 citing Fr. Diego de Córdoba Salinas, Crónica de la religiosísima provincia de las doces Apóstoles del Perú de la orden de N.P.S. Francisco, Lima 1651.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mariana de Jesús de Paredes. |

- "St. Mary Ann of Jesus of Paredes". American Catholic. Archived from the original on 2016-05-18. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- "MARY ANN de Paredes". Catholic Forum. Archived from the original on 2008-03-24. Retrieved 2007-05-28.