Mari (goddess)

Mari, also called Mari Urraca, Anbotoko Mari ("the lady of Anboto"), and Murumendiko Dama ("lady of Murumendi") is the goddess of the Basques. She is married to the god Sugaar (also known as Sugoi or Maju). Legends connect her to the weather: when she and Maju travel together hail will fall, her departures from her cave will be accompanied by storms or droughts, and which cave she lives in at different times will determine dry or wet weather: wet when she is in Anboto; dry when she is elsewhere (the details vary). Other places where she is said to dwell include the chasm of Murumendi, the cave of Gurutzegorri (Ataun), Aizkorri and Aralar, although it is not always possible to be certain which Basque legends should be considered as the origin.

Etymology

It is believed that Mari is a modification of Emari (gift) or Amari (mother + the suffix of profession) by losing the first vowel. The closeness in names between Mary and Mari may have helped pagans adapt their worship of Mari to undertake Christian veneration of the Virgin Mary.[1] The first known written citation of the "Dame of Amboto" was made by Charles V's chronicler Esteban de Garibay Zamalloa in his Memorial histórico español.[2]

Beliefs associated with Mari

Mari lives underground, normally in a cave in a high mountain, where she and her consort Sugaar meet every Friday (the night of the Akelarre or witch-meeting) to conceive the storms that will bring fertility (and sometimes disgrace) to the land and the people. Mari is served by a court of sorginak (witches), and is said to feed "on the negation and affirmation" (that is, on falsehood).

Occasionally the figure of Mari is linked to the kidnapping or theft of cows. The presence of Christian priests in those myths may indicate that they are Christian fabrications or distortions of original material. Legends do not recount any kind of sacrifices offered to Mari under normal circumstances, in contrast to food given to lesser spirits (lamiak, jentilak, etc.), as recompense for their work in the fields.

In various legends, Mari is said to have sons or daughters, but their number and character fluctuate. The two most well-known were her two sons, Atxular and Mikelatz. Atxular represents largely the Christianized Basque soul, becoming a priest after having learned from the Devil in a church in Salamanca and then having escaped. Mikelatz seems to have a more negative or wild character ; he is sometimes assimilated into the spirit of storms, Hodei, or embodied as a young red bull.

Another legend presents Mari as wife to the Lord of Biscay, Diego López I de Haro. This marriage may symbolize the legitimacy of the dynasty, much in the style of the Irish goddess marrying the kings of that island as a religious act of legitimacy. In any case, the condition that Mari imposes on her husband is that, while he could keep his Christian faith, he was obliged to keep it outside the home. Once, apparently after discovering that his wife had a goat leg instead of a normal human foot, he made the sign of the cross. Immediately after that act, Mari took her daughter, jumped through the window and disappeared, never to return. This account can be heard as delegitimizing the de Haro family, who had been placed as lords by the Castilian conquerors not long before this myth arose.

Other legends are more simple. For example, there is a legend that when one is lost in the wild, one only has to cry Mari's name loudly three times to have her appear over one's head to help the person find his or her way.

The people of Oñati believed that the weather would be wet when she was in Anboto, and dry when she was in Aloña. In Zeanuri, Biscay, they say that she would stay seven years in Anboto, then the next seven in a cave in Oiz called Supelegor. A similar legend in Olaeta, Biscay substitutes Gorbea for Supelegor.

A legend from Otxandio, Biscay tells that Mari was born in Lazkao, Gipuzkoa, and that she was the evil sister of a Roman Catholic priest. In other legends, the priest is her cousin Juanito Chistu, rather than a brother, and is a great hunter. She was said to take a distaff by the middle and walk along spinning, and leaving storms in her wake.

In Elorrieta, Biscay, it was said that she would be in her cave, combing her hair, and not even a shepherd could draw near to her. It was also said that her malign power did not extend to those who were innocent of sin.

Folklorist Resurrección María de Azkue ties Mari Urraca to a legend about a princess of the Kingdom of Navarre, widow of a 12th-century nobleman who lived in the Tower of Muncharaz in the valley known as the Merindad de Durango. She vanished at the time of his death and was said to have headed for the cave of Anboto. According to Azkue, Iturriza tells this story in his Historia de Vizcaya. Labayru in her Historia de Vizcaya doubts it.

Legends attached to the Lady of Murumendi, according to Azkue, include that she had seven brothers and was changed into a witch for her disobedience, and that the weather would be warm (or turbulent) when she walked about. In Beizama, Gipuzkoa, they say that if she stays in her cave and if, on the day of the Holy Cross, appropriate spells are cast, hail can be prevented. They also say that she and her husband once went to church in a cart and that upon leaving church, she rose into the air saying, "Domingo, Domingo el de Murua, siete hijos para el mundo, ninguno para el cielo" ("Domingo, Domingo of Murua, seven children for the world, none for heaven").[3]

Mari was associated with various forces of nature, including thunder and wind. As the personification of the Earth, she may have been worshipped in association with Lurbira.

Mari was regarded as the protectoress of senators and the executive branch. She is depicted as riding through the sky in a chariot pulled by horses or rams. Her idols usually feature a full moon behind her head.

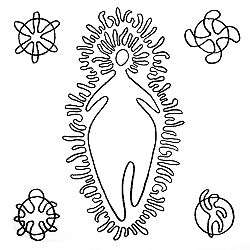

Mari is the main character of Basque mythology, having, unlike other creatures that share the same spiritual environment, a god-like nature. Mari is often witnessed as a woman dressed in red. She is also seen as a woman of fire, woman-tree and as thunderbolt. Additionally, she is identified with red animals (cow, ram, horse), and with the black he-goat.

Christianization

Santa Marina, a saint revered in the Basque Country, is a Christianized version of Mari. Basque women still invoke Santa Marina's protection against curses and for aid in childbirth.

The most accepted syncretism is with the Virgin Mary; she is widely venerated by modern Christian Basques.

Further reading

- Luis de Barandiarán Irízar (editor), A View From The Witch's Cave: Folktales of The Pyrenees (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1991). ISBN 0-87417-176-8

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mari. |

References

- This derives from articles in the Enciclopedia General Ilustrada del Pais Vasco Encyclopedia Auñamendi, which in turn cite Euskalerriaren Yakintza, Tomo I "Costumbres y supersticiones", by folklorist Resurrección María de Azkue (1864-1951). It notes that additional legends were recorded by Jose Miguel Barandiaran and Juan Thalamas Labandibar.

- Esteban de Garibay Zamalloa, Memorial histórico español: colección de documentos, opúsculos y antigüedades, Tomo VII.

- The meaning of "Murua" is obscure, but it might perhaps refer to the small village of Murua near Beizama. It may be impossible to be certain.

External links

- Mari and other Basque legends, Buber Basque Page