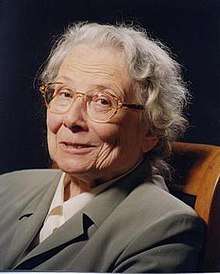

Margot Becke-Goehring

Margot Becke-Goehring (born 10 June 1914 in Allenstein; died 14 November 2009 in Heidelberg[1]) was a Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Heidelberg and she was the first female rector of a university in West Germany - the Heidelberg University.[2][3][4] She was also the director of the Gmelin Institute of Inorganic Chemistry of the Max Planck Society that edited the Gmelins Handbuch der anorganischen Chemie. She studied Chemistry in Halle (Saale) and Munich, and she finished her doctorate and habilitation at the University of Halle. For her research on the chemistry of main-group elements, she was awarded Alfred Stock Memorial Prize.[5][6] One of her most notable contributions to inorganic chemistry was her work on the synthesis and structure of poly(sulfur nitride), which was later discovered to be the first non-metallic superconductor.[7][8] For her success in editing the Gmelins Handbuch der anorganischen Chemie, she received the Gmelin-Beilstein memorial coin.[2]

Margot Becke-Goehring | |

|---|---|

Picture showing Margot Becke-Goehring (fair use only) | |

| Born | Goehring 10 June 1914 Allenstein |

| Died | 14 November 2009 |

| Nationality | Germany |

| Alma mater | University of Halle |

| Known for | First female rector of a university in West Germany and research on phosphorus-nitrogen and sulfur-nitrogen compounds |

| Spouse(s) | Friedrich Becke |

| Awards | Alfred Stock Memorial Prize (1961)

Member of the Academy of Sciences Leopoldina Member of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities Member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Honorary doctorate from the University of Stuttgart, Gmelin-Beilsteil Memorial Coin |

| Scientific career | |

| Doctoral students | Lieselotte Feikes, Rolf Appel |

Life

Becke-Goehring finished her Abitur in Erfurt in 1933.[2] She studied Chemistry in Halle (Saale) and Munich.[2] She completed her doctorate in 1938.[2] In 1944, she finished her habilitation at the institute of Karl Ziegler at the University of Halle.[2] After the Second World War, Becke-Goehring was evacuated by the American military government to the American occupation zone.[2] In 1946, she started as a lecturer for inorganic chemistry at the Heidelberg University.[2] Due to the destruction after the second world war, she had to write her first lecture notes based on her memory and test experiments in the chemistry laboratory.[3] In 1947, she became an extraordinary professor, and was promoted to full professor in 1959.[2] Among her doctoral students were Lieselotte Feikes and Rolf Appel.[2][9]

From 1966 to 1969, she was the first female rector of a university in West Germany .[2][4] She helped initiate a predecessor of BAFöG, a law that regulates state support for the education of students in Germany.[4] The German student movement of 1968 occurred during her time as a rector.[2] As a rector, she forbade Horst Mahler who was involved in the German student movement, from speaking at the university.[4] The movement and the resulting riots largely stopped the university reforms that she had initiated to deal with the financial problems and defects in buildings in the first years of increased student enrollment.[2] A university committee developed a new basic constitution of the university that disagreed with Becke-Goehring's views on free, non-politicizable teaching and research. Following this change, she stepped down as a rector, resigned as a civil servant and left the university in 1969.[2] In the same year, she became the director of the Gmelin Institute for Inorganic Chemistry of the Max Planck Society in Frankfurt where she was responsible for the Gmelin Handbuch.[2] She stayed as its director until her retirement in 1979.[2] She was also chairwoman of the scientific council of the Max Planck Society, a member of the board of management of the Society of German Chemists, and a member of the supervisory board of the Bayer AG.[2] She was married to the industrial chemist Dr. Friedrich Becke.[3]

Research

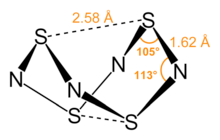

Initially publishing under the name Goehring and later Becke-Goehring, she researched the chemistry of the main-group elements.[6] Her initial work focused on sulphuric oxygen acids and sulphur halides.[10] Later, she was particularly interested in sulphur-nitrogen and phosphorus-nitrogen compounds.[6][10] Her work on tetrasulfur tetranitride (S4N4) started decades of research on this unusual and highly reactive inorganic heterocycle.[11] She was also able to determine the structure and chemistry of poly(sulfur nitride) which later turned out to be the first non-metallic superconductor.[7][8][12] Furthermore, she worked on eight-membered ring systems (e.g. heptasulfur imide S7NH[13] and N4S4F4), on six-membered rings (e.g. N3S3X3 (X=F,Cl) and N3[S(O)Cl]), and on ring systems involving sulfur, nitrogen and oxygen atoms as well as sulfur, nitrogen and carbon atoms.[10] Extensive investigations were also carried out on the reactions of PCl5 to phosphorus nitride chlorides (e.g. P3NCl12),[14][15][16] whereby several intermediate stages could be isolated and characterized.[10] In addition, she investigated phosphorus sulphides and other phosphorus sulphur compounds in the 1970s.[10]

Recognition

For her research in inorganic chemistry, she received the Alfred Stock Memorial Prize in 1961.[5][6] Due to her accomplishments, she was also a member of three academies of sciences: the Academy of Sciences Leopoldina,[18] the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities,[19] and the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities.[20] She also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Stuttgart.[2] For her work on the Gmelins Handbuch der anorganischen Chemie, she was awarded the Gmelin-Beilsteil Memorial Coin in 1980.[2] In 2017, the Heidelberg University started a lecture series in her remembrance.[21]

Publications

Besides her dissertation and habilitation, Becke-Goehring published several textbooks on Chemistry and books on the history of Chemistry:

- Die Kinetik der Dithionsäurespaltung (Dissertation 1938)[10][22]

- Über die Sulfoxylsäure (Habilitation 1944)[10]

- Becke-Goehring, Margot (1970). Komplexchemie Vorlesungen über Anorganische Chemie. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 9783642872150. OCLC 863980004.

- Fluck, Ekkehart; Becke-Goehring, Margot (1990). Einführung in die Theorie der quantitativen Analyse (7 ed.). Heidelberg: Steinkopff. ISBN 9783642503320. OCLC 858993979.

- Becke-Goehring, Margot (1980). Anorganische Chemie zwischen gestern und morgen : ein Fragment. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387099286. OCLC 7277426.

- Becke-Goehring, Margot (1983), Rückblicke auf vergangene Tage (Autobiography), Limited private print, Heidelberg.[23]

- Becke-Goehring, Margot (1990). Freunde in der Zeit des Aufbruchs der Chemie : der Briefwechsel zwischen Theodor Curtius und Carl Duisberg. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783642867774. OCLC 609780539.

- Becke-Goehring, Margot; Mussgnug, Dorothee (2005). Erinnerungen - fast vom Winde verweht : Universität Heidelberg zwischen 1933 und 1968 : zwei Vorträge, gehalten im Rahmen der Margot-und-Friedrich-Becke-Stiftung am 25. September 2004 in Heidelberg. Bochum: Dieter Winkler. ISBN 978-3899110579. OCLC 62901016.

Further reading

Rüegg, Walter; Fluck, Ekkehard (2013). Die Entwicklung der deutschen Universität. Heidelberg: Winter. ISBN 9783825373566. OCLC 874143733.

External links

- Video record of the talk "Anorganische Chemie zwischen gestern und morgen - wie ich sie erlebte" given by Margot Becke-Goetting at the Heidelberg University in 1992.

- Margot Becke-Goehring. Erste Professorin und erste Rektorin der Universität Heidelberg – Interview mit einer Zeitzeugin

- TV report from the SWR at the 19.7.2017: Geschichte & Entdeckungen, Margot Becke-Goehring (1914 – 2009)

References

- "Margot Becke-Goehring - Unlearned Lessons". www.unless-women.eu. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- "Margot Becke-Goehring" (PDF). www.gdch.de (in German). pp. 23–25. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- Schwarzl, Sonja M.; Servaty, Sabine; Kruse, Andrea (2002). "Zum Beispiel: Margot Becke-Goehring". Nachrichten aus der Chemie (in German). 50 (1): 77–78. doi:10.1002/nadc.20020500132. ISSN 1868-0054.

- "Margot Becke-Goehring - Universität Heidelberg". www.uni-heidelberg.de (in German). Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- "GDCh-Preise | Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker e.V." www.gdch.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-12-17.

- "Wer ist's? — Margot Becke-Goehring". Nachrichten aus Chemie und Technik (in German). 9 (19): 295. 1961. doi:10.1002/nadc.19610091903. ISSN 1868-0054.

- Goehring, Margot (1956). "Sulphur nitride and its derivatives". Quarterly Reviews, Chemical Society. 10 (4): 437. doi:10.1039/qr9561000437. ISSN 0009-2681.

- Kronick, Paul L.; Kaye, Howard; Chapman, Ernest F.; Mainthia, Shashikant B.; Labes, Mortimer M. (1962-04-15). "Electronic Properties of Polysulfur Nitride". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 36 (8): 2235–2237. Bibcode:1962JChPh..36.2235K. doi:10.1063/1.1732868. ISSN 0021-9606.

- Filippou, Alexander C.; Niecke, Edgar (2012-09-10). "Rolf Appel (1921–2012)". Angewandte Chemie. 124 (37): 9350. doi:10.1002/ange.201205250. ISSN 1521-3757.

- Werner, Helmut (2016). Geschichte der anorganischen Chemie: Die Entwicklung einer Wissenschaft in Deutschland von Döbereiner bis heute (in German). Weinheim, Germany. p. 330. ISBN 9783527693009. OCLC 964358572.

- Margot Goehring "Über den Schwefelstickstoff N4S4 Chemische Berichte 1947, Volume 80, pages 110–122. doi:10.1002/cber.19470800204

- Goehring, Margot; Voigt, Dietrich (1953). "Über die Schwefelnitride (SN)2 und (SN)x". Die Naturwissenschaften (in German). 40 (18): 482. doi:10.1007/BF00628990. ISSN 0028-1042.

- Margot Goehring, Hans Herb, Werner Koch "über Das Heptaschwefelimid, S7NH" Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie 1951, Volume 264, pages 137–143. doi:10.1002/zaac.19512640207

- Becke‐Goehring, Margot; Lehr, Wendel (1961). "Über Phosphorstickstoff-Verbindungen, XII. Ein neues Phosphornitrid-chlorid, P3NCl12". Chemische Berichte (in German). 94 (6): 1591–1594. doi:10.1002/cber.19610940624. ISSN 1099-0682.

- Becke‐Goehring, Margot; Mann, Theo; Euler, Hans Dietrich (1961). "Über Phosphorstickstoff-Verbindungen, X: Die Synthese von zwei neuen Phosphornitrid-chloriden". Chemische Berichte (in German). 94 (1): 193–198. doi:10.1002/cber.19610940129. ISSN 1099-0682.

- Latscha, Hans-Peter; Haubold, Wolfgang; Becke‐Goehring, Margot (1965). "Über Phospharstickstoffverbindungen. XX. Zur Kenntnis der Phosphornitrid-chloride, P4N3Cl11 und P5N3Cl16". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie (in German). 339 (1–2): 82–86. doi:10.1002/zaac.19653390112. ISSN 1521-3749.

- Goehring, M.: Über den Schwefelstickstoff N4S4 in Chem. Ber. 80 (1947) 110–122, doi:10.1002/cber.19470800204.

- "Mitgliederverzeichnis". www.leopoldina.org (in German). Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- "HAdW Mitglied". www.haw.uni-heidelberg.de (in German). Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- Jahrbuch der Göttinger Akademie der Wissenschaften 2008 (in German). Gottinger Akademie Der Wissenschaften. Walter De Gruyter Inc. 2009. p. 51. ISBN 9783110221602. OCLC 457150050.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Margot-Becke-Vorlesung" (in German). Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- Becke, Margot (1938). Die Kinetik der Dithionsäurespaltung (Thesis) (in German). Leipzig: Akad. Verlagsges.

- "Margot Becke-Goehing" (PDF) (in German).