Margaretta Faugères

Margaretta Faugères (October 11, 1771 – January 9, 1801) was the daughter of Ann Eliza Bleecker. She was an American playwright, poet and political activist. She became distinguished after the American Revolutionary War, in New York City's fashionable society, as a gifted and accomplished woman, although her married life was rendered unhappy by a profligate husband. After his death in 1798, she assisted in a female academy in New Brunswick; but her sufferings were said to have "broken her heart". She died at the early age of twenty-nine.[1]

Margaretta Faugères | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Margaretta V. Bleecker October 11, 1771 New York City |

| Died | January 9, 1801 Brooklyn |

| Occupation | author and political activist |

Early life and education

Margaretta V. Bleecker was born in New York City to John and Ann Eliza Bleecker, members of the American Dutch aristocracy. Shortly after her birth, the family moved to their country estate in Tomhannock, a small village north of Albany, where they lived in the "most perfect tranquility"[2] until the outbreak of the American Revolution.[3] Her mother was a prolific writer and had encouraged her to write as well. During the war Margaretta lost her grandmother, her aunt and her sister. Her mother was devastated by the loss and never fully recovered. Margaretta described their life after the war as "tolerable tranquility". Her mother developed a tendency towards depression and destroyed most of her own writings. Margaretta's tragedy continued with the loss of her mother when she was twelve years old.[4]

Sometime after her mother's death, she and her father moved to New York City where she continued her education and began to write.

Career

Faugères was committed to establishing her mother's reputation as a writer as well as her own. She started publishing her mother's poetry, what was left of it, in The New York Magazine in 1790.[5] Similarly she began publishing her own essays and poems in the same periodical. Her reputation as a poet grew and for a few years she was considered the "premier poet" of the magazine. She had strong political views and concentrated her writings around the anti-slavery movement, her support of the French Revolution and her disapproval of capital punishment.

In June 1791, The New York Magazine published Faugères essay Fine Feelings Exemplified in the Conduct of a Negro Slave in which she challenged Thomas Jefferson's claim that slaves lacked "finer feelings",[4] she wrote,

I cannot help thinking that their sensations, mental and external, are as acute as those of the people whose skin may be of a different colour; such an assertion may be bold, but facts are stubborn things, and had I not them to support me, it is probable I should not attempt to oppose the opinions of such an eminent reasoner.

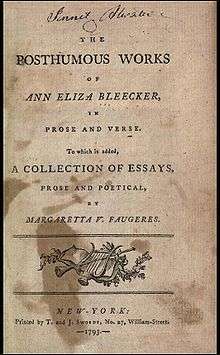

Her support of the French Revolution was probably shaped by her friendship with a French physician, Peter Faugeres, who shared her political views. They were married, in opposition to her father's wishes, on Bastille Day, July 14, 1792. Her marriage proved to be miserable; it became widely known that her husband abused her and within just a few years managed to squander her large fortune.[6] In 1793, she published The Posthumous Works of Ann Eliza Bleecker in Prose and Verse, to which is added a Collection of Essays, Prose and Poetical, a collection of her mother's work and her own. In 1795, she wrote Belisarius: A Tragedy. It was her major literary achievement, a blank-verse tragedy in four acts which echoed her views on human rights.

Faugeres opposed the death penalty for murder which made her view more radical than most. She felt it was inconsistent for a country which boasted of its freedom and happiness.[4] She wrote The Ghost of John Young in 1797. It was a six-page pamphlet arguing against the use of capital punishment. It was a poetic narrative in which she gave John Young's perspective from the grave.

Yes, I a murderer was by rage propell'd; and I have heard the last harsh decree,

but if the maniac is a murderer held, say cool deliberate actors, what are ye?

Not much is known of the remainder of her life. Her husband died of yellow fever in 1798. She taught school at an academy in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and later in Brooklyn. Her last published work, "Ode", was composed to support a July 4, 1798, speech given by Governor George Clinton, of whom she was a longtime supporter. The text was written to remind those of the price of revolution and the need for change. Faugeres saw beyond her privileged class and wrote about the democratic ideals of equality and justice. She sought radical change for American society and politics.

Personal life

Margaretta Van Wyck Bleecker and Peter Faugeres had two daughters, Eveanna Electa Faugeres (1795–1841) and Margaret Mason Faugeres (1797–1820). Eveanna married John Anthony Bleecker (her cousin) and had 8 children. Margaret married Edward P. Brady and was married 5 years before her death. She died on January 9, 1801, in Brooklyn and is buried next to her father in the Bowery Methodist Church cemetery.

References

- Ellet 1848, p. 246.

- Faugeres, Margaretta V. (1793). The Posthumous Works Of Ann Eliza Bleecker. New York: T.and J. Swords. pp. 1–19.

- Harris, Sharon M. (2003). Women's early American historical narratives. Penguin Classics. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-14-243710-7.

- Harris, Sharon M. (2005). Executing race: early American women's narratives of race, society, and the law. Ohio State University Press. pp. 113–130. ISBN 0-8142-5131-5.

- Brown, Charles Brockden; Philip Barnard; Stephen Shariro (2009). Wieland, Or, the Transformation: An American Tale, With Related Texts. Hackett Publishing. pp. 278–279. ISBN 0-87220-974-1.

- Griswold, Rufus Wilmot (1872). Female poets of America. J. Miller. pp. 35–37.

Attribution