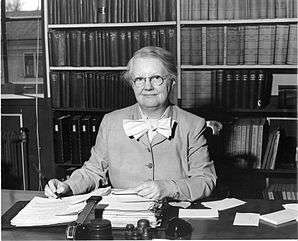

Margaret Cross Norton

Margaret Cross Norton (July 7, 1891 – May 21, 1984)[1]:197 served as the first State Archivist of Illinois from 1922 to 1957 and co-founded the Society of American Archivists in 1936, where she served as the first vice president from 1936–1937 and president from 1943–1945. She also served as editor of the American Archivist from 1946–1949. Norton was posthumously recognized in the December 1999 American Libraries article naming "100 of the most important leaders we had in the 20th century" for her influence on the archival profession.[2]

Margaret Cross Norton | |

|---|---|

Margaret Cross Norton | |

| Born | July 7, 1891 |

| Died | May 21, 1984 (aged 92) |

| Education | University of Chicago New York State Library School |

| Occupation | Librarian, Archivist |

| Parent(s) | Samuel and Jennie Norton |

Norton promoted the establishment of archives as a profession separate from history or library science and developed the American archival tradition to emphasize an administrator/archivist rather than an historian/archivist. She encouraged learning through experimentation, practical usage, and community discussion.[3] While editor of The American Archivist she emphasized technical rather than scholarly issues, believing that archival records were useful in ways other than scholarly research.[1]:197

By stressing the legal authority of government records, Norton believed archives could gain funding and government support through educating potential users about the legal protection records could provide them. Her influence and writings within the field of archives remain, for the large part, unchallenged.[1]:197

Biography

Early life

Margaret Cross Norton was born on July 7, 1891, to Samuel and Jennie Norton in Rockford, Illinois.[4] Samuel worked as the deputy county clerk, and Jennie was Winnebago County's deputy county treasurer. As the daughter of civil servants, Norton was accustomed to discussions between her parents on how best to execute their record-keeping responsibilities. Her mother's bookkeeping skills and her father's references to the Illinois Revised Statutes helped Norton recognize the "practical and legal values of local government records".[5] Norton later claimed that her archival philosophy was heavily influenced by her parents' work and household discussions.

Norton obtained her bachelor's and master's degrees in History from the University of Chicago in 1913 and 1914, respectively.[5] She then continued her education at the New York Library School in Albany, New York. After graduating with a Bachelor of Library Science in 1915, she worked as a cataloger for Vassar College Library in Poughkeepsie, New York. During this time, Norton attended an American Historical Association lecture by Waldo Gifford Leland, who emphasized the need for a national archives. While this lecture inspired Norton to pursue an archival career, she soon left her position at Vassar College to become a manuscripts assistant at the Indiana State Library in 1918.[5] After working there a year, she returned to the University of Chicago to complete a fellowship, then again moved on to become a cataloger at the Missouri State Historical Society from 1920 to 1921.[5]

While working at the Missouri State Historical Society, Norton was offered the position of Illinois State Archivist. At the time she was 30 years old.[1]:185

State archivist and professional impact

Norton accepted the position as Illinois State Archivist, but deferred her start date for more than four months to travel to the few archives that existed throughout the United States at the time. During her trip, she learned about the passive nature of the current American archives, and their practice to accept any records that were offered to their repository.[5] In April 1922 she began her 35-year career as Illinois State Archivist. Within months of her starting at the State Archives, Norton traveled to the Mississippi Valley Historical Association's meeting in Des Moines, Iowa. While there, Norton visited Cassius Stiles, the agency head of the State Archives.[5] Previously an administrative clerk, Stiles presented a new organization of record keeping. He arranged his collections by provenance and prepared administrative histories of each Iowa state department to aid in his work. A combination of this work style and Norton's early experience with public records aided in developing "her regard for the legal and administrative values of the records of government and the importance of their arrangement by source."[5] The availability of Hilary Jenkinson's Manual of Archive Administration "also confirmed Norton's theories on the "utility of governmental records and the importance of provenance."[5]

As one of three divisions of the Illinois State Library, the Illinois State Archives reported directly to the Illinois Secretary of State and had a minimal assistant staff.[5] Due to competition with the other two divisions, Norton often worked alone and faced budgetary restraints. While reorganizing and updating the archives, Norton discovered numerous historical and legal documents, including an 1823 Governor's letterbook explaining the chain of custody of a plot of land involved in a pending lawsuit. The information contained within this document was used to save millions of Illinois State dollars. In addition, Norton found other significant items, including an 1818 census record (when Illinois become a State in the Union), and records from the Illinois General Assembly during the time period in which Senator Abraham Lincoln and Senator Stephen Douglas were members.[5] These discoveries demonstrated the legal and administrative value of archival records.

In 1934, the Illinois State Arsenal Building was destroyed in a fire. The need for a new archival building that could protect the invaluable records housed within became a priority for Norton. She lobbied the state legislature for additional funding for a new, secure, and safe Archives building. Norton successfully secured $500,000 in appropriated funds from the General Assembly and $300,000 from the Federal Public Works Administration.[5] Designed according to Margaret Norton Cross' specifications,[19] the new building was "designed to protect the state's records of enduring value from the hazards of fire, humidity, heat, vermin, theft and exposure."[5] At this time the Illinois State Archive building was only the third public archives building in the United States[3] and during World War II, if an attack were imminent, the National Archives and Records Administration was prepared to move their most valuable materials to Norton's new building.[5]

Archives as a respected profession

Norton became a well-known proponent for the promotion of the utilitarian value of archives.

"One might conclude from the report that the ideal archivist is a scholar sitting in a remote ivory tower safeguarding records of interest only to the historian. In reality the archivist is at the very heart of his government and the archival establishment is a vital cog in its governmental machinery. Archives are legal records the loss of which might cause serious loss to citizens or the government."[6] -Margaret Cross Norton writing to dissent the verbiage put forth by the committee of archival training

Margaret Cross Norton was also a founding member of the Society of American Archivists, acting in a variety of roles throughout her decades-long tenure. Those roles included the society's first vice president from 1936 to 1938, the society's fourth president from 1943 to 1945), and a Council member and editor of the American Archivist from 1937 to 1942 and 1946 respectively.[7] Her activities in the American Historical Association (AHA), the American Library Association (ALA) and the National Association of State Libraries (NASL) are also well documented. Through these associations, she published writings and made public addresses broadcasting her focus on the utilitarian value of archives and a desire to distinguish the archive professionals as separate from historians and librarians.[3] One such address at the 1929 annual AHA meeting was met with skepticism. Six months later, however, a very similar speech with accompanying article was accepted and well regarded by the NASL. This and many other papers became landmarks for the push towards professional recognition of archivists as skilled professionals.

Pioneer for gender equality

In addition to helping the archival field develop as a profession free from historians and librarians, Norton was also a pioneer woman of her time. From 1936 to 1972, only about 15% of chair positions were held by women and female membership in the SAA and other professional associations was very limited.[8] Despite this, Norton made an impact on her colleagues. Her election as the first female president of the SAA was significant for the archival field and women in professional roles.[8] She believed in and upheld the solidarity of her own thought and practices and in turn, was one of the first females to hold many of her professional titles.[3] She also wrote numerous articles on the administrative aspect of the field. In one article, admitted "she deliberately overemphasized the administrative roles of archivist rather than their role as historians because too many so-called archivists shirked service to their institutions while writing or studying history for their own self-edification."[5]

Retirement and afterward

Norton retired in 1957. After retirement, she made every effort to limit her influence and weight in the workings of the Illinois State Archives. She also mentioned that she much preferred to walk by the lake and watch the bunnies.[1]:196 When she died at the age of 92 she left all of her personal holdings to the SAA. Upon the SAA's examination of her house, they discovered a framed picture of the Illinois State Archives Building on her bedside nightstand.[5]

Legacy

- Margaret Cross Norton Award: Established in 1985, the Midwest Archives Conference presents this award every two years for the best article published in the previous cycle of Archival Issues.[9]

- Margaret Cross Norton Fund: The Society of American Archivists uses the donated estate of Ms. Norton as an unrestricted fund "to further the educational activities of the foundation."[10]

- Margaret Cross Norton Building: Built from 1936-1938 and renamed in 1995, the Margaret Cross Norton Building houses 250 years of Illinois state history.[11]

Published works

- Norton, M. C. (1938) "Catalog Rules: Series for Archives Material." Springfield.

- Norton, M. C. (1975) "Norton on Archives: the writings of Margaret Cross Norton on archival and records management." Southern Illinois University Press.

- Norton, M. C. (1996) "Illinois Census Returns, 1820." Clearfield.

- Norton, M. C. "The Margaret Cross Norton Working Papers", 1924-1973, microfilm edition (Springfield: Illinois State Archives, 1993).

References

- Lawrimore, E. (2009). "Margaret Cross Norton: Defining and redefining archives and the archival profession". Libraries & the Cultural Record. 44 (2).

- Kniffel, L., Sullivan, P., McCormick, E. (1999, December). "100 of the most important leaders we had in the 20th century". American Libraries, 30(11), 38.

- Jimerson, Randal (2001). "Margaret Cross Norton Reconsidered". Archival Issues. 46 (1): 51.

- Lancaster, Donnelly (January 1998). "Fresh Focus: Before Archives: Margaret Cross Norton's Childhood, Education, and Early Career". Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists. 16 (1): 93–110.

- "Margaret Cross Norton: A Biographical Sketch". Office of the Illinois Secretary of State. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- Society of American Archivists 2nd Annual Meeting Springfield, Illinois Program 1938. Springfield, IL : Illinois State Archives. 1924.

- Campbell, Ann Morgan (1984). "The Society of American Archivists". The American Archivist. 47 (4): 469–474. JSTOR 40292718.

- Brown, Stephanie M. "A woman in the archives: the legacy of Margaret Cross Norton". Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- "Margaret Cross Norton Award". MAC: Midwest Archives Conference. midwestarchives.org. Retrieved 2017-04-22.

- "SAA Foundation". Society of American Archivists. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- White, Jesse. "Illinois State Archives" (PDF). Illinois State Archives. Retrieved 22 April 2018.