Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder

Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder, Marc Gerard and Marcus Garret[1] (c. 1520 – c. 1590) was a Flemish painter, draughtsman, print designer and etcher who was active in his native Flanders and in England. He practised in many genres, including portraits, religious paintings, landscapes and architectural themes.[2] He designed heraldic designs and decorations for tombs. He is known for his creation of a print depicting a map of his native town Bruges and the illustrations for a Dutch-language publication recounting stories from Aesop's Fables. His attention to naturalistic detail and his practice of drawing animals from life for his prints had an important influence on European book illustration.[3] His son Marcus the Younger became a prominent court painter at the English court.[4]

Life

Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder was born in Bruges, Flanders, as the son of Egbert Gheeraerts and his wife Antonine Vander Weerde. Egbert Gheeraerts was a painter who had moved from an unknown location to Bruges. Some scholars believe that Gheeraerts' patronymic indicates that he likely came from the Northern Netherlands. His wife Antonine, on the other hand, was a native of Bruges. Egbert became a master of the Guild of Saint Luke of Bruges on 20 January 1516.[3]

The exact date of birth of Marcus Gheeraerts is not known. On the basis of archival sources about the life of his father, it can be deduced that he was born between 1516 and 1521.[3] Not long after her husband's death, Marcus' mother remarried Simon Pieters, who was also a painter and probably a native of the Northern Netherlands. The couple had six children with whom Marcus was raised. This explains why he was sometimes referred to as Marcus Pieters. After the death of his stepfather Simon Pieters in early 1557, Marcus Gheeraerts became the guardian of his half-brothers and sisters. Marcus's mother died on 8 August 1580.[3]

The master or masters of Marcus Gheeraerts are not known. The most obvious candidate is his stepfather Simon Pieters. Art historians believe that he started his training with Simon Pieters and later worked in the workshop of his guardian Albert Cornelis. It is speculated that he may have had other masters but there is no agreement as to their identity. He likely trained outside Bruges to learn the craft of engraver, which was not generally practised at a high level in Bruges.[3]

There is no information about Gheeraerts in the registers of the Sint-Lucas guild in Bruges for the period from 1522 to 1549. This absence has been interpreted as an indication that he left his hometown to study in Antwerp or abroad. From 1558 onwards a number of documents demonstrate that Gheeraerts was resident in Bruges. On 31 July 1558, he entered the artisan and saddle maker's guild of Bruges as a master painter. In the same year, he was elected second board member of the guild, suggesting that he already enjoyed considerable professional recognition. From April to September 1561 Gheeraerts was the first board member.[3]

On 3 June 1558, Marcus Gheeraerts married Johanna Struve. The couple had three children, of whom two are known by name, a son later referred to as Marcus the Younger and a daughter called Esther. A third child died at a young age and was buried in 1561.[3]

Gheeraerts developed a professional career as a painter, etcher and designer. He was active as a designer of heraldic motifs. On 10 September 1559, he was commissioned to provide designs for the tombs of Mary of Burgundy and Charles the Bold in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges. He drew the patterns for the lavishly decorated metal ornaments, the colorful coats of arms and two copper angels that were attached to the sides of the tombs. In 1561 Marcus Gheeraerts was commissioned to complete a triptych of the Passion of Christ that had been commenced by the prominent painter Bernard van Orley. The painting had remained unfinished after van Orley's death in 1542. Originally intended for the church of the monastery of Brou near Bourg-en-Bresse (Ain department, France), which Margaret of Austria had built, the triptych was transferred to Bruges after her death. Gheeraerts completed it. Margaret of Parma later decided to place the triptych in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges.[3]

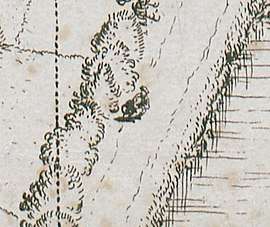

Gheeraerts was further commissioned in 1561 to make a print depicting a map of his hometown. He completed the work in one year. The map is one of the earliest examples of a perspective city map that is correctly displayed.[3] It is during this period that Gheeraerts most likely painted the Triumphant Christ (collection of the Memling museum in Old St. John's Hospital in Bruges).[3]

Marcus Gheeraerts became involved in the Calvinist community in Bruges and became a leader of the local church community. Whereas Calvinism was initially tolerated, the religious persecution of Calvinists commenced in 1567 with the arrival of new governor of the Low Countries, the Duke of Alva. In 1566 he participated in protests against the arrest of Calvinists in Bruges. He reflected in his art on the religious turmoil and iconoclasm of his time. As a Calvinist and artist he seemed to have had mixed feelings about the Iconoclasm of his religious group: he condemned idolatry of images but did not agree with the wholesale destruction of religious images by the Iconoclasts. In 1566 or shortly after, he created a print referred to as the Allegory of Iconoclasm that shows a composite rotting head of a monk. The head appears to rise up from a rocky outcropping. Myriad little figures swarm over the rocks. They enact 22 different scenes that used to be denoted by alphabetical keys which have not survived.[6] Inside the gaping mouth a diabolical mass is celebrated. On the pâté of the head sits a pope-like figure under a canopy on a throne surrounded by bishops and monks. Indulgences and rosaries are pinned up on the staves and various rituals and processions take place and are labelled with letters. In the foreground Protestant iconoclasts are smashing altarpieces, religious sculptures, other church-related items and hurling them into a fire.[7][8] The print is a condemnation of Catholic idolatry in all its forms and shows the Calvinists as cleansing the world of this perceived evil.[6] Gheeraerts is believed to have followed up this print with more politically tainted prints, which resulted in 1568 in a prosecution for producing caricatures of the pope, the king and Catholicism.[3]

Fearing that he would be condemned to death in the criminal proceedings against him, Gheeraerts fled in 1568 to England with his son Marcus and his workshop assistant Philipus de la Valla. His wife and daughter remained in Bruges. The verdict in his case was pronounced at the end of 1568. He was convicted and the punishment was permanent banishment and forfeiture of his entire fortune.

Gheeraerts took up residence in London upon his arrival in England in 1568. He was joined by his daughter in May 1571 likely after her mother had died. After the death of his wife in Bruges, the artist married in England his second wife, Sussanah de Critz. His wife was a sister of Queen Elizabeth I's serjeant-painter, John de Critz, another Flemish painter who had fled to England.The couple had two daughters and one son. The only child surviving into adulthood, Sarah, later married the famous French-born English limner Isaac Oliver. Just as before in Bruges, Gheeraerts made drawings and etchings and continued his painting activities. As there was a keen demand for portrait paintings in England, Gheeraerts started to paint portraits, which he had not done while still in Flanders.[3]

Art historians do not agree as to whether Gheeraerts returned to his native Flanders around 1577 to continue his career in Antwerp. In 1577 a 'Mercus Geeraert Painter' was registered as a master in the Guild of Saint Luke of Antwerp and paid registration fees for the years 1585 and 1586. It is not clear whether this Mercus referred to Marcus the Elder or to Marcus the Younger. Some art historians believe that Marcus the Elder registered in the Antwerp Guild in order to be able to legally work with Antwerp printers for the publications on which he worked. Others believe that he actually worked in Antwerp and point to the various publications printed in Antwerp on which he collaborated.[3]

Marcus Gheeraerts had various pupils during his career. In 1563, 13-year-old Melchior d'Assoneville became an apprentice of Gheeraerts in Bruges. Melchior d’Assoneville later became a sculptor and decorative painter and while living in Mechelen he was the master of Hendrik Faydherbe. His workshop assistant Philipus de la Valla who fled with him to England may also have been a pupil of Gheeraerts although he is sometimes referraed to in contemporary records as a servant. It is not certain whether Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder was the teacher of his son Marcus the Younger. There are different views on this, but it is likely that he was but that his son also received training with other artists, who may have included other Flemish emigrants in England, such as Lucas de Heere and John de Critz.

The date of death of Gheeraerts is not known but it must have been before 1599.[3]

Work

General

.jpeg)

Gheeraerts was a painter, draughtsman, print designer, etcher and ornamemtal designer. As many of his paintings were lost as a result of the Iconoclasm of the 16th century, he is now mainly known for his work as a printmaker and print designer. He was a keen innovator and experimented with etching at a time when woodcut and engraving were dominant techniques. For example, his 1562 birds-eye view of the town of Bruges was etched on 10 different plates, and the resulting map measures 100 x 177 cm.[9]

Paintings

Very few paintings have been attributed to Gheeraerts with much certainty. He did not sign any of his paintings. It is documented that he finished the triptych of the Passion of Christ that had been commenced by the prominent painter Bernard van Orley. The triptych was later damaged during the period of Iconoclasm and largely repainted in 1589 by Frans Pourbus the Younger during restoration work. It is not clear from the current state of the work, which parts were painted by which painter. It has been suggested that Bernard van Orley started the centre of the panel and that Marcus Gheeraerts completed the outer areas. A replica of the scene of The lamentation of Christ appeared on the art market (Hampel Fine Art sale of 27 June 2019, lot 551) and was attributed to Gheeraerts. Another version of the Lamentation also attributed to Gheeraerts is in the Saint Amands Church of Geel.[10]

The panel of the Triumphant Christ (Memling museum in Old St. John's Hospital in Bruges) has been attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts. The Lazarus and the rich man (Catharijneconvent Museum in Utrecht) has been attributed to Gheeraerts but this attribution is not uncontested.[3]

Gheeraerts the Elder was known as a portrait painter. The traditional attribution to Gheeraerts of the Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, also referred to as the Peace portrait is still a matter of contention. The monogram "M.G.F". on the portrait can apply to both Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder and his son Marcus the Younger. Some art historians regard it as a collaboration of father and son Gheeraerts. A Portrait of Prince William I of Orange (Blair Castle, Scotland) has also been attributed to Gheeraerts.[3]

Two works depicting celebrations, the Fête at Bermondsey and A village festival (Hatfield House, Herefordshire), England), formerly attributed to Flemish artist Joris Hoefnagel, were attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder in 2015.[11] An inscription on the first painting indicates it was painted on commission by the Flemish merchant Jacob Hoefnagel, a brother of Joris Hoefnagel and a resident of London. The inscription also mentions that Jacob Hoefnagel wanted the picture to depict all the fashions that could be seen in England. Gheeraerts followed this instruction by depicting the figures in costumes from England, France, Venice and other European countries. These costumes were based on a publication depicting various costumes compiled and illustrated by Flemish émigré artist Lucas de Heere. It is believed both paintings depict marriage celebrations. The location of the Fête is the river bank of the Thames while the Festival is placed in an imaginary landscape. In both paintings, a procession is moving from right to left headed by two men carrying large oval cakes, two violinists and a man bearing a vase with rosemary tied with ribbons. The faces of the figures are rendered with precision and are likely portraits of members of the Flemish community in England. The paintings may have been intended to showcase the dignity and piety of the Flemish émigré community in England and to assert their proper place in their adopted country. It is believed that the man looking at the viewer appearing in both paintings is a self-portrait of the artist Gheeraerts.[12]

Karel van Mander wrote in his Schilderboeck from 1604 that Gheeraerts was a good landscape painter, who "often had the habit of including a squatting, urinating woman on a bridge or elsewhere."[13] A similar detail is seen in one of his fable illustrations and his map of Bruges. No landscape paintings by Gheeraerts' hand are currently attributed to him but some of his works such as the Fête, the Festival and the Triumphant Christ contain important landscape elements.[3]

The description of the art collection of Cornelis van Hooghendorp made at the end of the 16th century included five paintings by Gheeraerts. These included a landscape with cows, an allegorical representation with a "scene of the night when the devil sowed bad seed", a representation of Mary on the flight to Egypt and two paintings on parchment. In 1563 Marcus Gheeraerts also painted a triptych for the church of the friars minor recollect in Bruges.[3]

The painting style of Gheeraerts was initially influenced by Bernard van Orley. After 1565 he followed the Italianate style of painting of prominent Antwerp history painter Maerten de Vos. His painting style is further close to that of the little-known Vincent Sellaer.[10]

Prints

Gheeraerts was active as a printmaker and print designer during his time in Flanders and in England. The best-known print works he created before he left for England are the map of Bruges, the Allegory of Iconoclasm (both discussed above) and the emblematic fable book De warachtighe fabulen der dieren (The true fables of the animals).[3][13]

De warachtighe fabulen der dieren

This book was published in 1567 in Bruges by Pieter de Clerck. Marcus Gheeraerts etched the title page and the 107 illustrations for each fable that his friend, Edewaerd de Dene, had written in his local Flemish verse. Gheeraerts initiated and financed the publication, which was printed to the highest standards of its time as a luxurious object with three different fonts. Each fable takes up two facing pages: on the left-hand side the illustration is displayed headed with a proverb or saying and some verse underneath it while on the right-hand the fable and its moral are told. It was the first emblematic fable book and set a trend for similar books.

The principal source of the text in the book were Les fables du très ancien Ésope written by the French humanist Gilles Corrozet and published in Paris in 1542. A second source was the Aesopi Phrygis et aliorum fabulae, a collection of fables in Latin that was published on the Antwerp printing presses of Christophe Plantin in various editions from 1660. A third source for the fables writings of natural history such as Der Naturen Bloeme (The Flower (i.e. choice) of Nature), a Middle Dutch natural history encyclopedia, written in the thirteenth century by the Flemish writer Jacob van Maerlant and the Dutch-language natural history compilation Der Dieren Palleys (The palace of the Animals), published in Antwerp in 1520. A final source for the fables are contemporary emblemata books such as the Emblemata of Andrea Alciato and an emblem of Joannes Sambucus.[14] Illustrations made by Bernard Salomon for an edition of Aesop's fables published in Lyon in 1547 and a German edition with prints by Virgil Solis published in Frankfurt in 1566 were the basis for the motifs of Gheeraerts. He gave his subjects greater naturalism than these artists. About 30 images were Gheeraerts' own invention.[15]

Gheeraerts added another 18 illustrations and a new title page for a French version of the Fabulen that was published in 1578 under the title Esbatement moral des animaux.[16] A Latin version, Mythologia ethica, was published in the following year with a title page likely based on a drawing by Gheeraerts. The copper plates were used in books well into the 18th Century and the fable series was copied by artists all over Europe. Gheeraerts also etched a second series of 65 illustrations for the fable book Apologi Creaturarum, which was published in Antwerp in 1584. However, the etchings were smaller than those of the first series and this book never achieved the same popularity as the original one.[14] Gheeraerts' images were also used in publications until the 18th century in the Dutch Republic, Germany, France and Bohemia.[15]

Notes

- Many name variations: Marcus I Garret, Marcus the elder Geeraerts, Marcus Gerard the Elder, Marcus I Gheeraerts, Marcus Garret the Elder, Marcus Gheeraerts, Marcus the Elder Gerard, Marcus Geeraerts the Elder, Marcus the elder Gheeraerts, Marc Gerard, Marcus I Gheeraerts, Marc Gerards, Marcus I Gerard, Marc Geerarts, Marcus I Geeraerts, Marcus Geerards, Marc Gheeraerts, Marcus the Elder Gerards, Marcus Gheeraerts (I), Marcus Garret (I), Marcus Garrett, Marcus Garrett (I), Marcus Geeraerts, Marcus Geeraerts (I), Marcus Geerarts, Marcus Geerarts (I), Marcus Gheerhaerts, Marcus Gheerhaerts (I), Marcus Gerard, Marcus Gerard (I), Marcus Gerards, Marcus Gerards (I), Marcus (The Elder) Geeraerts, Marcus Gheeraerts Elder, Marcus Elder Gheeraerts, m. gheeraedts the elder, Marcus Geraers

- Marcus Gheeraerts (I) at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- Margot Thybaut, Marcus Gheeraerts de oude een monografie, Master thesis, University of Ghent, Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte, vakgroep Kunst-, Muziek- en Theaterwetenschappen, voor het verkrijgen van de graad van Master, Promotor: prof. dr. Maximiliaan P.J. Martens (in Dutch)

- Strong, Roy, "Elizabethan Painting: An Approach through Inscriptions. III. Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger." The Burlington Magazine 105 (1963): 149–157

- Although not particularly sympathetic to the Calvinist iconoclasts, it is mainly critical of the Catholic Church. The etching may have been the main reason why Gheeraerts had to flee to England in 1568. (British Museum, Dept. of Print and Drawings, 1933.1.1..3, see also Edward Hodnett: Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder, Utrecht 1971, pp. 26-7)

- Alastair Duke: Chapter Calvinists and 'papist idolatry': the mentality of the image-breakers in 1566 in Dissident Identities in the Early Modern Low Countries, Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2009, pp 196-197

- Marcus Gheeraerts I (Attributed), Composite rotting head of a monk representing an allegory of iconoclasm in the British Museum

- David Freedberg, Art and iconoclasm, 1525-1580 The case of the Northern Netherlands, J.P. Filedt Kok et al. (eds.), Kunst voor de Beeldenstorm [Cat. Exhib., Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum], Publisher: Rijksmuseum; Staatsuitgeverij, January 1986, pp.69-84

- De koperplaten van de kaart van Marcus Gerards, 8 December 2017 (in Dutch)

- Marcus Gheeraerts I, The lamentation of Christ at Hampel Fine Art auctions

- Edward Town, "A fête at Bermondsey" an English landscape by Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder, The Burlington magazine 157.2015,1346, 309-317

- Remy Debes, Dignity: A History, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 179–180

- Marcus Geerarts biography in Schilder-boeck (1604) by Karel van Mander

- D. Geirnaert en P.J. Smith, The sources of the Emblematic Fable Book 'De warachtighe fabulen der dieren (1567), in: J. Manning, K. Porteman and M. van Vaeck, The emblem tradition and the Low Countries, Turnhout, 1999, p. 23-38

- Edward Hodnett, Francis Barlow: First Master of English Book Illustration, 1978, University of California Press, pp. 67-71

- Irène Fabry-Tehranchi, The ‘Esbatement moral des animaux’ : a 16th century French adaption of Aesopian fables and their illustration

Reference books

- Reginald Lane Poole (Mrs.): Marcus Gheeraerts, Father and Son, Painters, The Walpole Society, 3 (1914), 1–8.

- Arthur Ewart Popham: The etchings of Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder, Print Collector's Quarterly, 15 (1928), 187–200.

- Albert Schouteet, De zestiende-eeuwsche schilder en graveur Marcus Gerards, Bruges, Druk. A. & L. Fockenier 1941.

- Edward Hodnett: Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder of Bruges, London, and Antwerp, Utrecht (Haentjens Dekker & Gumbert) 1971.

- William B. Ashworth: Marcus Gheeraerts and the Aesopic connection in seventeenth-century scientific illustration, Art Journal', 44 (1984), 132–138.

- Eva Tahon: Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder, in: M. P. J. Martens (red.), Bruges and the Renaissance: Memling to Pourbus, Bruges (Stichting Kunstboek / Ludion) 1998, 231–238.

- Mikael Lytzau Forup: 125 fabler med illustrationer af Marcus Gheeraerts den Ældre [Danish: 125 fables with illustrations by Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder], Odense (University Press of Southern Denmark) 2007. (The book features Gheeraerts' entire Aesop series of 125 fable illustrations and 3 title pages.)