Manzanar Children's Village

The Manzanar Children's Village was an orphanage for children of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II as a result of Executive Order 9066, under which President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast of the United States. Contained within the Manzanar concentration camp in Owens Valley, California, it held a total of 101 orphans from June 1942 to September 1945.

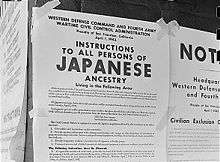

Incarceration of Japanese Americans

Issued a little over month after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, on February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 authorized military commanders to designate military zones from which "any or all persons may be excluded." On March 2, 1942, General John L. DeWitt and the Western Defense Command issued a public proclamation that established Military Areas 1 and 2, encompassing all of California, the western halves of Washington and Oregon, and Southern Arizona. Although the executive order had not specified who was to be excluded, DeWitt's proclamation made it clear that Japanese American residents would be required to vacate the newly created exclusion zone, and Public Law 503, passed by Congress on March 20, 1942 and signed into law by the President the following day, created penalties of up to $5,000 and one year in prison for violating the military restrictions.[1]

Approximately 5,000 Japanese Americans moved through a short-lived "voluntary evacuation" program — many of them into what they were assured would remain a "Free Zone" in eastern California but would later fall within the scope of exclusion — however, most remained in their homes while they waited for further information.[2] The first civilian exclusion order was issued on March 24, 1942, and in April, Alaska was under military orders to evacuate its Japanese residents as well (due to the territory's small Japanese population, it was not designated with any exclusion zones). Over the next five months, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were transported from the West Coast and Southern Arizona to isolated inland camps.

The orphans of Children's Village

Prior to 1942, most orphans of Japanese ancestry lived either with relatives or foster families, or were housed in one of three California orphanages.[3] The Shonien and Maryknoll Home in Los Angeles and the Salvation Army Home in San Francisco cared specifically for children of Japanese ancestry, although the mainstream institutions where white children were typically placed would from time to time accept a Japanese American child.[4] About two-thirds of the orphans who would reside in Children's Village during the war came from these three homes, and several Shonien, Maryknoll and Salvation Army staff members would serve as their caretakers in camp.[5]

Others were not orphans before the war. Following Japan's December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI carried out large-scale arrests of Japanese Americans suspected of fifth column activity, mainly Issei community leaders and business owners (including Shonien director Rokuichi Kusumoto[6]). Over 5,500 men were detained, most subsequently sent to Department of Justice-run internment camps.[7] Children who did not have relatives to take them in after their father's arrests became orphans and later wound up in Children's Village.[8]

Several children brought to the Village lived with non-Japanese foster families before the war. Because their foster parents were not subject to exclusion from the West Coast, these children were either extracted from their homes after officials learned that they were part or full Japanese, or, influenced by propaganda that promised strict penalties for harboring Japanese, their guardians turned them over to authorities themselves.[9]

Half of the children confined in the Manzanar orphanage were under age seven when they arrived; 29 percent were less than four years old.[3] Nineteen of these 101 orphans were of mixed-race heritage,[3] some with as little as one-eighth Japanese ancestry,[9] including several children who were unaware of their racial background until army authorities identified them by scouring confidential orphanage and federal records.[5][9][10]

During the war

Orphanage board and staff members attempted to dissuade authorities from sending orphans to camp without success. .[9][11] Col. Karl R. Bendetsen, "determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must all go to camp,"[5][12] gave the order to begin removing children from orphanages on April 28, 1942.[9] The Assistant Director of the Shonein, Lillian Iida, a 29-year-old Nisei woman, fought against the Army plan to divide the orphans equally amongst the staff and send each staff member, with orphans, to an internment camp as a new family unit. The result of her opposition to the Army's plan was the building of the Children's Village at Manzanar. Lillian and her new husband, Harry Matsumoto, then ran the Children's Village for the early years of the war. The nuns of the Maryknoll Home managed to find foster homes outside the exclusion zone for 26 of the 33 orphans in their charge.[9] The 61 remaining children in Maryknoll, Shonien and the Salvation Army Home were slated for removal. On June 23, 1942, they were bused, under armed guard, with several adult caretakers from Los Angeles to Manzanar.[3] Over the next few months, approximately thirty more children from Washington, Oregon and Alaska, mostly orphans who had been living with non-Japanese foster families, would arrive in Manzanar. Infants born to unmarried mothers in other WRA camps were also sent to Children's Village over the next three years.[9]

Children's Village consisted of three barracks — one for staff apartments and communal areas, and two that contained the children's dormitories — located across from barracks 28 and 29, near the hospital, at the northwest end of the Manzanar complex.[3] With running water and independent kitchen and bathroom facilities, the orphanage was largely self-contained and operated separately from the rest of the camp. Harry and Lillian Matsumoto, social workers who accompanied the Shonien orphans and served as superintendents of Children's Village, led the children in a daily schedule of breakfast, a Christian service, school, homework, recreation, and dinner. Younger children went to bed at 7:30 p.m., and a curfew of 9:00 p.m. was enforced for the rest of the Village.[3]

The children had very little interaction with other Japanese Americans in Manzanar. Because the orphanage facilities were more self-sufficient than the family barracks, there was little need to leave the Village. They ate inside the orphanage with their caretakers, separate from other camp inmates, who ate their meals in communal mess halls assigned by block. Additionally, they were ostracized by other children, who had been told by their parents not to play with the orphans.[8][13] This isolation, and the fact that many orphans came to Manzanar together and had known each other and their staff guardians for years, made the closure of Children's Village at the end of the war especially difficult.

After the war

In late 1944, Roosevelt issued Public Proclamation 21, allowing Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast starting in January 1945, and most of the WRA-run concentration camps closed over the course of that year.[14] When word came that Manzanar would begin to shut down, camp officials and orphanage staff began the process of determining where to send the children. Most were returned to the group homes they had been taken from or sent to live with relatives or guardians. Some, whose records had been lost during their removal or did not have an appointed guardian, remained in Children's Village while authorities attempted to find relatives or at least determine the child's legal residence.[3] These unclaimed children were placed with adoptive parents or sent to foster homes and other institutions when the Children's Village closed in September 1945.

The history of the Manzanar Children's Village was largely unknown, even within the Japanese American community, until the late 1980s, when Francis Honda, an orphan confined in Children's Village during the war, gave testimony of his experiences at Manzanar for the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearings.[9][15] Manzanar Children's Village is no longer standing, but there is a National Park Service-operated informational slide about the orphanage at its former site, and the Children's Village Oral History Project, archived at the Center for Oral and Public History at California State University, Fullerton, contains interviews with former residents and staff members.[3]

References

- Brian Niiya. "Public Law 503" Densho Encyclopedia (accessed 22 May 2014).

- Brian Niiya. "Voluntary evacuation," Densho Encyclopedia (accessed 4 Apr 2014).

- Catherine Irwin. "Manzanar Children's Village," Densho Encyclopedia (accessed Feb 19, 2014)

- Helen Whitney, "Care of Homeless Children of Japanese Ancestry during Evacuation" (M.A. thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1948), 13.

- Emmy E. Werner. Through the Eyes of Innocents: Children Witness World War II (Basic Books, 2001), 86.

- Ford Kuramoto. A History of the Shonien, 1914-1972: An Account of a Program of Institutional Care of Japanese Children in Los Angeles (San Francisco: R & E Research Associates, 1976), 42.

- Densho. "About the Incarceration: Arrests of Community Leaders" (accessed Feb 19, 2014)

- Glen Kitayama. "Manzanar" Densho Encyclopedia (accessed Feb 19, 2014)

- Renee Tawa. "Childhood Lost: The Orphans of Manzanar," Los Angeles Times March 11, 1997.

- James L. L. Dickerson. Inside America's Concentration Camps: Two Centuries of Internment and Torture. (Chicago Review Press, 2010), 95.

- Judy Vaughn. The Bells of San Francisco: The Salvation Army with Its Sleeves Rolled Up. (RDR Books, 2005), 81.

- Michi Nishiura Weglyn. Years of Infamy (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976), 76-77.

- Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston. Farewell to Manzanar (Random House, 2012), 114.

- Brian Niiya. "Return to West Coast," Densho Encyclopedia (accessed 4 Apr 2014).

- Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied.

Further information

Children's Village Oral History Project. California State University, Fullerton. Center for Oral and Public History.

Catherine Irwin, Twice Orphaned: Voices from the Children's Village of Manzanar (Fullerton, CA: Center for Oral and Public History, 2008).

Lisa Nobe, "The Children's Village at Manzanar: The World War II Eviction and Detention of Japanese American Orphans." Journal of the West 38.2 (April 1999): 65-71.

Helen Whitney, "Care of Homeless Children of Japanese Ancestry during Evacuation" (M.A. thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 1948).