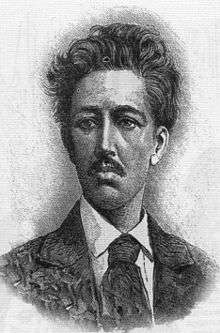

Manuel Acuña

Manuel Acuña Navarro (27 August 1849 – 6 December 1873) was a 19th-century Mexican writer. He focused on poetry but also wrote some novels and plays. He died by suicide at age 24. It is not certain why he killed himself, but it is thought that he did so because of a woman.

Manuel Acuña | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 27, 1849 |

| Died | December 6, 1873 (aged 24) |

| Nationality | Mexican |

Early life

Acuña was born in the city of Saltillo, Coahuila, on August 27, 1849 to Francisco Acuña and Refugia Navarro. He was taught how to write and read at an early age. His parents received the first letter. Subsequently studied at the College Josefino Saltillo city and around 1865 he moved to Mexico, where he entered as a boarder at the College of San Ildefonso, where he studied mathematics, Latin, French, and Philosophy. Subsequently, In January 1868 he began his studies at the School of Medicine.[1][2]

Acuña lived at a time at which Mexican society was dominated by philosophical-positivist intellectuality. Furthermore, he was living as a romantic tendency in poetry was occurring.

In January 1868, Acuña initiated his studies in medicine at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. He was a distinguished student, though he never completed his medical studies. During the first months there, he lived in a room in the ex-convent of Santa Brígida. From here he was transferred to a room at the medical school, the same one that some years before was inhabited by another Mexican poet, Juan Díaz Covarrubias. In this room, many of the young writers of that time met: Juan de Dios Peza, Manuel M. Flores, Agustín F. Cuenca, Gerardo M. Silva, Javier Santamaría, Juan B. Garza, Miguel Portilla, and Vicente Morales among others.

Career

It was in 1868 when Acuña initiated his brief literary career. He first became known with a poem he wrote for the death of one of his close friends Eduardo Alzúa. In the same year, encouraged by the cultural renaissance that followed the triumph of the Republic, he participated, along with Agustín F. Cuenca and Gerardo Silva, among others, in the founding the Nezahualcóyotl Literary Society, in which he presented his first verses.

The works presented in the society were published in the magazine El Anáhuac (Mexico 1869) and in a pamphlet of the newspaper La Iberia named “Literary Essays of the Nezahualcóyotl Society”. This pamphlet is considered as one of the works of Acuña, since it contains, in addition to works of other writers, eleven poems and an article in prose of his own. He was only 24 years old when he had made a name for himself.

On May 9, 1871, a dramatic work that he wrote called El pasado (The Past) was released. This work was well received by the public and critics recognized him as an outstanding poet.

Rosario de la Peña was the woman that was the most intimately related to Acuñas’s last years. She was the great love of his life. In fact, most of Acuña's friends were in love with this woman (although she never had a formal relationship with any of them). Her house was frequently turned into a social gathering place for these poets, where each one exposed his new verses and debated philosophy.

Among his works are: Nocturno; and Entonces y hoy which depicted a violent anarchism.[3]

Death

Acuña killed himself[4] on December 6, 1873 by ingesting potassium cyanide. It is said that tears welled up in his closed eyes, in accordance to advice given in a poem that he wrote: "como deben llorar en la última hora, los inmóviles párpados de un muerto" ("As the immovable eyelids of a dead man must cry in the last hour")[2] His unrequited love for Rosario de la Peña was said to be the motive for his suicide.[2]

The day Acuña died, he was guarded by his friends at the medical school. On December 10, Acuña was buried at the cemetery “Campo Florido”, with the attendance of representatives of literary and scientific societies, as well as a huge crowd of people that admired him. His brother, Juan de Dios Peza (his best friend), Gustavo Baz, Eduardo F. Zárate and Justo Sierra gave their last goodbyes to Acuña. Finally, his body was transferred to “La Rotonda de los hombres ilustres”, where a monument was erected in his honor.

Role within Mexican literature

Acuña was a well-known figure amongst Mexican writers; furthermore, some of them were his friends. Acuña influenced most of them in their writing. It was not necessarily in the way they wrote, but that some of their works were done in such a way that they wanted to remember him for a long time. After Acuña’s death, José Martí wrote a poetic letter to Acuña.[5]

References

- "Biografia de Manuel Acuna". Los-poetas.com. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Humberto Garza (October 10, 1998). "Los Poetas". Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- Garzanti, Aldo (1974) [1972]. Enciclopedia Garzanti della letteratura (in Italian). Milan: Garzanti. p. 4.

- Hills, Elijah Clarence; Morley, S. Griswold (1913). "Notes". Modern Spanish Lyrics. Holt. p. 312. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Manuel Acuña, por José Martí". Rjgeib.com. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

| Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

External links

- Hojas Secas de Manuel Acuna - Poema de amor at www.poema-de-amor.com.ar

- "Nocturno a Rosario" por Manuel Acuña at www.rjgeib.com

- Works by or about Manuel Acuña at Internet Archive

- Works by Manuel Acuña at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)