Manteo (Native American leader)

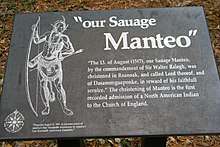

Manteo was a Native American Croatan, the chief of a local tribe that befriended the English explorers who landed at Roanoke Island in 1584. In 1585 the English returned to Roanoke, arriving too late in the year to plant crops and harvest food, and Manteo helped the colonists make it through the harsh winter. He traveled to England on two occasions, in 1584 and 1585. After staying there, he was among those who sailed for the New World in 1587 along with Governor John White and his colonists, who founded the failed settlement later known as "The Lost Colony". On Sunday, August 13, 1587, Manteo was christened on Roanoke Island, making him the first Native American to be baptized into the Church of England.

Manteo | |

|---|---|

Manteo | |

| |

| Croatan, Algonquian peoples leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | Unknown |

| Known for | Roanoke Colony, travels to England, co-operation with English settlement |

Early life

Very little is known of Manteo's early life. He was born into the Croatan tribe, a small Native American group living in the coastal areas of what is now North Carolina. They may have been a branch of the larger Roanoke people or allied with them.[1] The Croatan lived in current Dare County, an area encompassing the Alligator River, Croatan Sound, Roanoke Island, and parts of the Outer Banks, including Hatteras Island. Manteo first entered the historical record through his encounter with English explorers in 1584, when Sir Walter Raleigh dispatched the first of a number of expeditions to Roanoke Island to explore and eventually settle the New World.

Travel to England

Early English encounters with the natives were friendly, and Manteo became one of the first Native Americans to travel to England. Despite the difficulties in communication, the explorers persuaded "two of the savages, being lustie men, whose names were Wanchese and Manteo" to accompany them on the return voyage to London,[2]:63 in order for the English people to report both the conditions of the New World that they had explored and what the usefulness of the territory might be to the English.[3]:159[4]:346–347

Once safely delivered to England in September 1584,[2]:64 Manteo and Wanchese soon caused a sensation at court. Raleigh's priority, however, was not publicity but rather intelligence about his new land of Virginia, and he restricted access to the exotic newcomers. He assigned the scientist Thomas Harriot the job of deciphering and learning the Carolina Algonquian language,[2]:70 using a phonetic alphabet of his own invention in order to effect the translation.

Both Wanchese and Manteo were hosted at Raleigh's London residence, Durham House. Unlike Manteo, Wanchese evinced little interest in learning English and did not befriend his hosts, remaining suspicious of English motives in the New World. He soon considered himself as a captive of the English rather than as their guest.[2]:64 By Christmas of 1584, Harriot learned to converse in Carolina Algonquian with the two Croatans. Accounts suggest that Manteo was far more co-operative than Wanchese.[2]:73

Harriot and Manteo spent many days in one another's company; Harriot interrogated Manteo closely about life in the New World and learned much that was to the advantage of the English settlers.[2]:73 In addition, he recorded the sense of awe with which the Native Americans viewed European technology:

Many things they sawe with us...as mathematical instruments, sea compasses...[and] spring clocks that seemed to goe of themselves – and many other things we had – were so strange unto them, and so farre exceeded their capacities to comprehend the reason and meanes how they should be made and done, that they thought they were rather the works of gods than men.[2]:73

Manteo and Wanchese returned to the New World in April 1585, sailing with Sir Richard Grenville's expedition in the Tiger. They reached the warm waters of the Caribbean in just 21 days.[2]:98 The expedition was led by Sir Ralph Lane, and was accompanied by Harriot who, having mastered Carolina Algonquian, would act as translator between the local tribes and the English settlers.

Records indicate that Manteo and Wanchese traveled again to England later in the same decade. Following the voyage, Manteo, Wanchese, and the English returned to Roanoke.[3]:179 It is speculated that Sir Walter Raleigh chose to have Manteo accompany him on his journey to England in order to better acquaint him with certain elements of English culture; specifically, so that he would be able to improve his skills in the English language and so that he might gain a deeper understanding of the Anglican Christian faith.[4]:373[5]:79

Lost Colony

In 1587 Manteo returned to Roanoke along with Governor John White's ill-fated expedition to plant a permanent English colony in the New World. Manteo was involved in several nighttime attacks which took place in 1587.[4]:354–355[5]:188 The Native Americans had informed the English that some of their men were killed. To seek revenge, the English attempted to plot an attack on the Roanoke, who they believed had killed the English men. But, the English killed several Croatan people by mistake.[5]:188 As a mediator between the English and the Native Americans, and due to his loyalty to the English people, Manteo was caught in the middle. He had mixed feelings about the attacks and understood the points of views of both sides.[5]:188

Relations with the Roanoke colonists

_(14761424616).jpg)

Manteo was essential to English–Native American communications during those early voyages to and explorations of the New World organized by Raleigh. The relationship that Manteo shared with the English serves as an early example of positive racial and cultural relations in North America and also as a unique example of race relations within the context of Western Civilization. Manteo was a trusted friend, teacher, and guide to the English settlers while remaining loyal to his native people during early American history, when English and Native American relations were highly unstable. Manteo is one of the foremost examples of positive race relations in early American history.

Manteo was useful to the English people in several ways. He served as a guide and translator to the English. Manteo and the English people were able to learn about each other's language and culture. Manteo at times was also a mediating figure between the English people and the Native Americans. Because of his status among the English people and because he was in peaceful communication with them, some of the Croatan considered Manteo to be disloyal to them and a traitor at times of conflict.[5]:204

Although Manteo is an example of positive relations between the English and the indigenous peoples, there were other Native Americans who were friendly toward the English as well. Wanchese[4]:346–348 and other Native Americans such as Towaye[3]:179[4]:352, 357 shared relationships with Manteo and the English people.

Religion

Manteo is recognized as being the first Native American who became an Anglican Christian.[4]:355 Manteo was possibly converted to Anglican Christianity by Raleigh. Some historians believe that Raleigh promoted this as a political maneuver to further Manteo's role in working with the English. Upon conversion, Manteo retained his given name.[5]:190 Manteo may have assisted in helping the English convert other Native Americans to Christianity as well.[4]:351 In 2008, the 125th Annual Convention of the Episcopal Diocese of East Carolina approved the commemoration of the Baptism of Manteo, along with that of Virginia Dare, to be kept on August 17 of each year.

Death and legacy

Following the abandonment of the settlement, Manteo was lost to history. The details related to Manteo's death are unknown. He may have left with colonists during the abandonment of the Roanoke site.[4]:357[5]:188 The town of Manteo, North Carolina is named after him.[6]

Notes

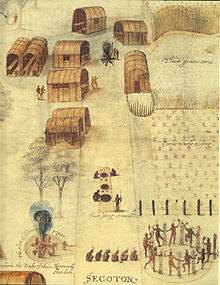

- "Indian Towns and Buildings of Eastern North Carolina", Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, National Park Service, 2008, accessed 24 Apr 2010

- Milton, Giles, Big Chief Elizabeth - How England's Adventurers Gambled and Won the New World, Hodder & Stoughton, London (2000)

- Mancall, Peter C. Hakluyt's Promise: An Elizabethan's Obsession for an English America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Vaughan, Alden T. "Sir Walter Raleigh's Indian Interpreters, 1584-1618," The William and Mary Quarterly 59.2 (2002)

- Kupperman, Karen Ordahl. Indians and English: Facing Off in Early America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000.

- "Manteo & Roanoke Island On the Croatan & Roanoke Sounds". Outer Banks of North Carolina. 8 April 2008.

External links

- Manteo at thelostcolony.org Retrieved April 2011

- Account of the Roanoke settlements Retrieved April 2011