Mansion House Hospital

Mansion House Hospital, was a Union hospital, during the American Civil War, formed after Union occupation of Alexandria, Virginia and the seizure of the Mansion House Hotel.[1]

| Mansion House Hospital | |

|---|---|

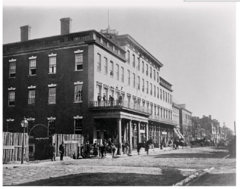

The Mansion House Hotel served as a hospital during the occupation of Alexandria, Virginia by Union forces, during the Civil War | |

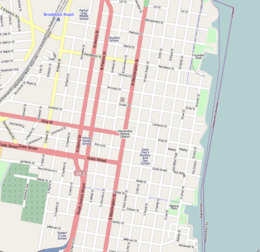

Location within Alexandria, Virginia  Mansion House Hospital (Virginia)  Mansion House Hospital (the United States) | |

| General information | |

| Type | Hotel |

| Address | 121 N. Fairfax Street |

| Town or city | Alexandria, Virginia |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 38°48′19″N 77°2′32″W |

| Opened | 1860 |

| Renovated | 1906 |

| Demolished | 1970s |

History

Mansion House Hotel

The hospital was built in the old Mansion House Hotel, an establishment also known as Green’s Hotel operated by James Green.[2] By 1848, furniture manufacturer James Green had acquired the former Bank of Alexandria building to convert into a hotel. A four-story addition on the building’s east side was built around 1855.[3] and made it the largest hotel in Alexandria.[2] Green received a notice in early November 1861, stating he had three days to vacate the hotel.[2]

Military hospital

On December 1, 1861, Mansion House Hospital was opened as a General Hospital.[2] Parts of the nearby Bank of Alexandria building at 133 North Fairfax Street were also used as part of the hospital, as were parts of the Carlyle House behind the hotel.[4]

The hospital used female nurses, which by the spring of 1862, resulted in harsh treatment and prejudice towards nurses based on their gender. Nurses such as Mary Phinney, however, kept accounts and “helped set the stage for women not just in nursing, but in the medical profession as a whole.”[5]

In March 1862, there was a court case concerning conditions at The Mansion Hospital, concerning the behavior of surgeon J. B. Porter, after allegations of mistreatment of patients were published in the New-York Tribune and Washington National Republican on February 6, 1862. A Court of Assembly met on the issue in February 1862 led by General William H. French, and determined that the complaints were not valid, and that “the Court, from its own observation, cannot speak too highly of the condition of the Mansion Hospital, which is exhibited in the fact, that out of 500 patients, there have been but 32 deaths.”[6]

On September 20, 1862, people began using the hospital as a First Division General Hospital, and it was the largest of the confiscated buildings used as a military hospital in the city,[2] out of 30 total converted hospitals in the city.[5] It could hold up to 700 sick and wounded soldiers.[3] The hospital was the largest Union hospital in the region, with 500 beds.[2]

After the war

Following the surrender of the Confederacy on April 9, 1865, the Mansion House Hospital was returned to the Greens and reopened as a hotel.[5] First again called the Mansion House Hotel, it was then acquired by new proprietors in the early 1880s and renamed Braddock House.[3] By 1886, it was advertised as the only first-class hotel in the city.[3]

By the 1970s, the building was vacant and deteriorating.[2] The Northern Virginia Park Authority acquired the entire property, and despite protests from some preservationists, in early 1973[3] a portion was torn down that decade to restore the nearby John Carlyle House and open area for the Carlyle House Historic Park. A part of the old hospital was, however, partly preserved in what is now an adjacent bank building.[2]

Media

In 2016 PBS broadcast a miniseries, Mercy Street, set in the hospital.[1] The PBS drama is set in 1862.[7] Some of the characters are based on real historical figures associated with the hospital, for example the Green family and nurse Mary Phinney von Olnhausen.[8]

See also

- Mary Phinney

- Benjamin Franklin Stringfellow

- Emma Green

References

-

Sarah Coster (March 2011). "Nurses, Spies and Soldiers: The Civil War at Carlyle House" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2016-01-19.

A skinny 21 year-old at the start of the war, Stringfellow used his cunning and bravery to gather intelligence for the Confederacy. He daringly crossed enemy lines multiple times, sneaking into both Alexandria and Washington.

- "Mansion House Hospital". City of Alexandria, Virginia.

- "Out of the Attic: Green's Mansion House". alextimes.com. Alexandria Times. November 23, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- "Letters to the Editor Opinion". washingtonpost.com. Washington Post. March 3, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- "Nurses, Spies and Soldiers: The Civil War at Mansion House and Carlyle House". PBS.org. PBS. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- "The Mansion Hospital At Alexandria; Vindication of Dr. J.B. Porter". nytimes.com. The New York Times. March 22, 1862. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- "Experience Mercy Street". The City of Alexandria. June 4, 2017.

- Knutsen, Kristian (February 5, 2016). "Exploring Mercy Street: The Uniform". wptblog.org. Wisconsin Public Television. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

External links

- D. Toler, Pamela. "Heroines of Mercy Street".

- Michael E. Stevens (10 August 2007). As If It Were Glory: Robert Beecham's Civil War from the Iron Brigade to the Black Regiments. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-7425-5944-8.

- Mary Searing O'Shaughnessy (14 September 2012). Alonzo's War: Letters from a Young Civil War Soldier. Fairleigh Dickinson. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-1-61147-555-5.

- Sheep Set. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1866. pp. 216–.