Manor House Street railway station

Manor House Street station (also known as Kingston Street station) was the original terminus station of the Hull and Selby Railway, opened in 1840 adjacent to the Humber Dock in Kingston upon Hull, England. In 1848 the station was superseded by Hull Paragon station after which it was primarily used for goods traffic.

- Not to be confused with the Manor House street goods station used by the MS&LR, commonly known as English Street station

| Manor House Street | |

|---|---|

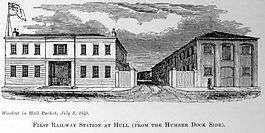

View from Humber Dock side | |

| Location | |

| Place | Kingston upon Hull |

| Coordinates | 53.739°N 0.339°W |

| Grid reference | TA096282 |

| Operations | |

| History | |

| 1840 | Opened |

| 1848 | closed for passengers |

| June 1853 | opened for passengers |

| 1854 | closed for passengers |

| 1960 | closed for freight |

| Disused railway stations in the United Kingdom | |

| Closed railway stations in Britain A B C D–F G H–J K–L M–O P–R S T–V W–Z | |

As a goods station the facility was known as Railway Street Goods station. Most of the buildings were demolished in 1959 as part of a modernisation programme converting the English Street Goods station into a main regional depot.

Sidings remained on the site until the 1980s when housing development occupied the western part of the site. The site of the station buildings site was developed as a multi-storey housing development Freedom Quays in the 2000s.

History

Manor House Street station (1840–1854)

The station was constructed as the original Hull terminus of the Hull and Selby Railway. The station was located on a site of around 5 acres (2.0 ha) adjacent to the Humber Dock and Kingston Street. The main building was a two-storey structure of white brick and stone, known as Railway Office, was constructed facing onto Humber Dock. The office was 100 by 70 feet (30 by 21 m) deep by wide with waiting rooms, and ticket and parcel offices on the ground floor; a passage led from the station front to the train shed behind; the first floor contained the company offices including the director's room.[1][2] The design is thought to be by James Walker and John Timperley, with Simminson & Hutchinson as the building contractors, ironwork by James Young.[3]

The main train shed was 170 by 72 feet (52 by 22 m) long by wide, connected at the east end to the offices, with trains arriving at the west end. There were four lines of track, and raised platforms at either side; the trainshed roof was supported on cast iron columns. An exit in the north wall led to a station road, which separated the passenger station from the goods shed to the north.[4][2]

The railways workshops of around 5,000 square yards (4,200 m2) were located west of the station, also facing Kingston Street, and included facilities for engine, wagon and carriage work, with power supplied by a 10 hp stationary engine.[4][map 1]

The goods shed and warehouse was a two-storey building 270 by 45 feet (82 by 14 m) long by wide, with a single line of track within, and two on either side, all running the entire length. Within the building the floor was 2 feet (0.61 m) above the level the track for ease of loading. The second floor had access to the lower throughout the shed, allowing movement from train to warehouse under cover.[4][2] In addition to the goods warehouse the company had a wharf nearby at Limekiln Creek.[5][map 2]

On the opening day (1 July 1840) after a return trip from Hull to Selby a banquet with speeches was held in the upper warehouse.[6] Public services started on 2 July, and goods service on 19 August.[7]

Initially passenger trains pulled into the station by a rope and capstan – this led to an accident where the uncontrolled momentum imparted led to the train crashing through the booking office wall. Later the train would have the engine detached, run round and used to shunt the train backwards into the trainshed. The railway followed the practice used on early British railways of stopping the train outside the station for ticket inspections.[8]

In 1847 an act of Parliament allowed the construction of a new station, this opened in May 1848 as Hull Paragon station, and the station at Kingston Street closed to passengers.[9] From June 1853 a suburban service of passenger trains running on the Victoria Dock Branch Line began terminating at the Station, running to and from Victoria Dock. The service was ended in 1854.[10]

Railway Street goods station (1854–1961)

After the opening of Paragon station the old station was used as a goods station. Expansion was soon required and land including the old Gaol (west of Manor House Street) and houses on Bell Vue Terrace were acquired and demolished and the station expanded.[11][12][13] In 1858 the existing buildings were demolished and the site redeveloped in one piece as a goods station.[12][14][13]

The new goods station was designed by NER architect Thomas Prosser; the main building was 300 feet (91 m) long, initially with four platforms. The station was expanded in the mid 1860s increasing the number of platforms to right. A second shed was added to the west adjoining Railway Street. Built for the NER, the warehouse also provide service to other railways with running powers to Hull; the Lancashire and Yorkshire and London and North Western Railway;[15] the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway used a wharfe and warehouse at Limekiln creek for lighter services across the Humber, replaced c. 1866 with a new warehouse and water channel at Railway Creek, built as replacement for the loss of the former during the construction of the new West Dock.[16]

In 1959 a modernisation plan envisaged converting the English Street Goods station into one of the seven main depots in BR's North-eastern region, to be known as Hull Central goods depot.[17] The Railway Street station was demolished in 1961.[14]

The Railway Street site remained in use as part of the Central Good's operations (opened October 1960[18]) handling wagonload traffic and used for storage.[19]

Some sidings remained on the site until 1984, when housing was built on the entrance tracks. Much of the station site was redeveloped as Freedom Quays, a housing and multi-storey car park development between 2003–8; the northern part is used as a Ship chandler;[20] Hull Marina's boat yard is also located on the site.

References

- MacTurk 1970, p. 71.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 340.

- Fawcett 2001, p. 32.

- MacTurk 1970, p. 72.

- Tomlinson 1915, pp. 340–1.

- MacTurk 1970, p. 50.

- Tomlinson 1915, p. 341.

- MacTurk 1970, pp. 78–9.

- Hoole 1986, p. 45.

- Hoole 1986, pp. 45–6.

- MacTurk 1970, p. 130.

- Ordnance Survey. Town plans, 1:1056, 1855–6; 1:2500, 1891–3

- Fawcett 2001, p. 33.

- Allison, K.J., ed. (1969). "Railways". The City of Kingston upon Hull. A History of the County of York, East Riding. 1. Victoria County History.

- Fawcett 2003, p. 83.

- See Hull and Selby Railway, Railway Creek, Limekiln creek, and Albert Dock.

- Railway Engineering Abstracts, 14–6: 53,

The English Street goods depot at Hull has been modernised and enlarged to provide one of the seven main concentration depots of the North Eastern Region, B.R., and is to be known in future as Hull Central Goods Depot

Missing or empty|title=(help) - Annual Reports and Accounts, British Transport Commission, 1, 31 December 1960,

The reconstructed goods depot at Hull Central opened in October, and all sundries traffic for the area is now concentrated here

Missing or empty|title=(help) - Fawcett 2005, p. 213.

- Brigham, T., ed. (May 2008), "Hull Marina Gateway Site – Fruit Market Strategic Development Area – Assessment of Archaeological Potential" (PDF), Humber Archaeology Report, Humber Field Archaeology (262), Railway Station (site of), p.25, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012, retrieved 24 March 2020

Sources

- Fawcett, Bill (2001), A History of North Eastern Railway Architecture, 1, North Eastern Railway Association

- Fawcett, Bill (2003), A History of North Eastern Railway Architecture, 2, North eastern Railway Association

- Fawcett, Bill (2005), A History of North Eastern Railway Architecture, 3, North eastern Railway Association

- Hoole, Ken (1986), A regional history of the railways of Great Britain. Vol 4, The North East (3rd ed.), David and Charles

- MacTurk, G.G. (1970) [1879], A History of the Hull Railways, (reprint)

- Tomlinson, William Weaver (1915), The North Eastern Railway; its rise and development, Andrew Reid and Company, Newcastle; Longmans, Green and Company, London

Maps

- 53.7388°N 0.3408°W Hull and Selby railway, Hull workshops

- 53.7368°N 0.3424°W Hull and Selby railway, Limekiln Creek warehouse