Malagasy giant chameleon

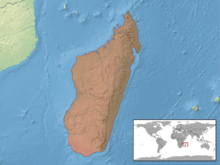

The Malagasy giant chameleon or Oustalets's chameleon (Furcifer oustaleti ) is a large species of chameleon which is endemic to Madagascar,[2] but also has been introduced near Nairobi in Kenya (though its current status there is unclear).[3]

| Malagasy giant chameleon | |

|---|---|

_male_Montagne_d%E2%80%99Ambre.jpg) | |

| Male, Montagne d’Ambre National Park | |

_female.jpg) | |

| Female, Anjajavy Forest | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Iguania |

| Family: | Chamaeleonidae |

| Genus: | Furcifer |

| Species: | F. oustaleti |

| Binomial name | |

| Furcifer oustaleti (Mocquard, 1894) | |

| |

Habitat

F. oustaleti occurs in a wide range of habitats, even among degraded vegetation within villages, but is relatively rare in primary forest.

Description

With a maximum total length (including tail) of 68.5 cm (27 in), F. oustaleti is considered the largest species of chameleon,[2] but that claim is occasionally contested by the Parsons chameleon Calumma parsonii as the Parsons tends to be more heavily built but slightly shorter in length.

in the Anjajavy Forest

in the Anjajavy Forest_male_Anja_Community_Reserve.jpg) male, Anja Community Reserve

male, Anja Community Reserve_female_head_Andasibe.jpg) female, Andasibe, Moramanga

female, Andasibe, Moramanga_young_female_Isalo.jpg) young female, Isalo National Park

young female, Isalo National Park

Diet

The diet of F. oustaleti includes invertebrates such as large insects as well as some vertebrates such as small birds and reptiles. This is also one of several chameleon species that are known to consume fruit. F. oustaleti is known to regularly consume the fruit of Grangeria porosa, Chassalia princei, and Malleastrum gracile, and will do so even during the wet season, suggesting that fruit is not consumed just to obtain water.

Typically, prey is acquired with a long, muscular tongue, while fruit is seized directly with the jaws, but occasional exceptions to this rule have been recorded. In one unusual case however, this species was recorded grasping fruit bearing twigs with the zygodactyl feet and bringing them closer for consumption. Amongst reptiles, this level of food manipulation with the forelimbs is otherwise only documented in some species of monitors lizards[4] and Chamaeleo namaquensis. The latter is also known to feed on plants. [5]

_male_feeding_Anja_Community_Reserve_1e.jpg) male feeding 1 of 4

male feeding 1 of 4_male_feeding_Anja_Community_Reserve_2e.jpg) male feeding 2 of 4

male feeding 2 of 4_male_feeding_Anja_Community_Reserve_3e.jpg) male feeding 3 of 4

male feeding 3 of 4_male_feeding_Anja_Community_Reserve_4e.jpg) male feeding 4 of 4

male feeding 4 of 4

Etymology

The generic name, Furcifer, is derived from the Latin root furci meaning "forked" and refers to the shape of the animal's feet.[6]

The specific name, oustaleti, is a Latinized form of the last name of French biologist Jean-Frédéric Émile Oustalet, in whose honor the species is named.[7]

References

- Jenkins RKB, Andreone F, Andriamazava A, Anjeriniaina M, Brady L, Glaw F, Griffiths RA, Rabibisoa N, Rakotomalala D, Randrianantoandro JC, Randrianiriana J, Randrianizahana H, Ratsoavina F, Robsomanitrandrasana E (2011). "Furcifer oustaleti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T172866A6932058. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T172866A6932058.en.

- Glaw, Frank; Vences, Miguel (2007). A Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Madagascar (3rd ed.). Cologne, Germany: Vences & Glaw Verlags. ISBN 978-3929449037.

- Spawls S, Drewes R, Ashe J (2002). A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa. Cologne, Germany: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-656470-1.

- Takahashi, Hiroo (December 2008). "Fruit Feeding Behavior of a Chameleon Furcifer oustaleti: Comparison with Insect Foraging Tactics". Journal of Herpetology. 42 (4): 760–763. doi:10.1670/07-102R2.1. JSTOR 40060573.

- Burrage, Bryan (October 1973). "Comparative ecology and behavior of Chamaeleo pumilus pumilus (Gmelin) and C.namaquensis A. Smith (Sauria: Chamaeleonidae)". Annals of the South African Museum. 61: 75–79.

- Le Berre, François; Richard D. Bartlett (2009). The Chameleon Handbook. Barron's Educational Series. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7641-4142-3.

- Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Furcifer oustaleti, p. 198).