Mala Pasqua!

Mala Pasqua! (Bad Easter!) is an opera in three acts composed by Stanislao Gastaldon to a libretto by Giovanni Domenico Bartocci-Fontana. The libretto is based on Giovanni Verga's play, Cavalleria rusticana (Rustic Chivalry) which Verga had adapted from his short story of the same name. Mala Pasqua! premiered on 9 April 1890 at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome, six weeks before Pietro Mascagni's opera Cavalleria rusticana which was also based on Verga's play. Bartocci-Fontana's libretto adds some elements that were not in Verga's original and expands on others. The name of the Santuzza character was also changed to Carmela, but the basic plot and setting remain the same. Its title refers to the curse which Carmela places on Turiddu, the lover who had spurned her: "Mala Pasqua a te!" ("May you have an evil Easter!"). Following its Rome premiere Mala Pasqua! had a few more performances in Perugia and Lisbon, but it was completely eclipsed by the phenomenal success of Mascagni's opera. After the 1891 Lisbon run it was not heard again until 2010 when it was given a semi-staged performance in Agrigento, Sicily.

| Mala Pasqua! | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Stanislao Gastaldon | |

Adolfo Hohenstein's illustration for the opera's libretto published in 1890 by Ricordi | |

| Librettist | Giovanni Domenico Bartocci-Fontana |

| Premiere | 9 April 1890 Teatro Costanzi, Rome |

Background

Giovanni Verga's "Cavalleria rusticana" ("Rustic Chivalry") was originally published in Vita dei campi (Life in the Fields), his 1880 collection of short stories depicting Sicilian peasant life. The story itself is less than 2000 words long and is told almost entirely through the dialogue of its characters: Lola, Turiddu (Lola's lover), Alfio (Lola's husband), Santa (Turiddu's spurned lover), and Nunzia (Turiddu's mother). At the urging of the actress Eleonora Duse, Verga adapted the story for the theatre, doubling its length and elaborating on the plot. Santa became Santuzza and a much more central character than she had been in the short story.[1] Four new characters were also added: Brasi, Camilla, Filomena, and Pipuzza, villagers who comment on the actions of the protagonists. Cavalleria rusticana, a play in one act and nine scenes, premiered with Duse as Santuzza on January 14, 1884 at the Teatro Carignano in Turin and became Verga's most successful stage work. Duse toured it in Italy and abroad and it was the basis for several films and at least three operas, the first of which was Mala Pasqua!

The enormous success of Stanislao Gastaldon's 1881 salon song, "Musica proibita", and his subsequent compositions in that genre had made him famous throughout Italy. In 1887 at the age of 26, he turned his attention to composing his first opera, Fatma, an opera-ballet in four acts. However, he set the project aside in 1888 when the music publisher Sonzogno announced a competition for one-act operas, open to all young Italian composers who had not yet had an opera performed on stage. The three winners (selected by a jury of prominent critics and composers) would be staged in Rome at Sonzogno's expense. Gastaldon decided to enter with an opera based on Cavalleria rusticana. His librettist, Giovanni Domenico Bartocci-Fontana, a lawyer by training and a poet by inclination, wrote to Verga asking permission to adapt the play. Verga wrote back to him on June 3, 1888 to say that he was happy to give his permission but added that the subject as it was treated in the play did not seem suitable for an opera libretto.[2] Unbeknownst to Verga, another young composer, Pietro Mascagni, entered the same contest at virtually the last minute with his opera Cavalleria rusticana, also based on the story. Gastaldon withdrew his work early in the competition when he received an offer from Sonzogno's rival, Ricordi, to publish it and arrange for its premiere at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome.[3] He expanded his original one-act version to two acts, and then three. Bartocci-Fontana's libretto added some elements that were not in Verga's original and expanded on others as well as changing the name of the Santuzza character to Carmela. However the basic plot and setting remained the same. It was given the title Mala Pasqua! from the curse which Santuzza placed on Turiddu in the original play: "Mala Pasqua a te!" ("May you have an evil Easter!"). The prominent Romanian soprano Elena Theodorini, who had already sung in the premieres of several new operas in Italy, read the score and agreed to sing the key role of Carmela[4]

Performance history

Mala Pasqua! premiered on April 9, 1890 at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome with Elena Theodorini and Giuseppe Russitano as Carmela and Turiddu. The opera ran for a total of four performances. Proceeds of the first three were to go to the patronesses' committee of the Tiro a Segno Nazionale (Italy's national association for target shooting) who also financed the production. Amongst the audience at the premiere were the Princess Odescalchi, Lina Crispi (wife of the Prime Minister Francesco Crispi) and several prominent politicians including Paolo Boselli, Federico Seismit-Doda, and Luigi Miceli.[5] Although the critics were dismissive of the work, they did note that it found favour with the opening night audience with loud cheers and requests for Gastaldon to come before the curtain for an ovation even before the performance was finished. The Catholic journal, La Civiltà Cattolica, did not review the performance but recorded its outrage at the opera's depiction of a religious procession with a priest carrying the Eucharist during a tale of "sordid affairs and adultery" and called it a "sacrilege and vile insult". According to the journal, the devout Catholics walked out at this point, leaving an audience that consisted largely of "freemasons, riflemen, and an assortment of vulgar people."[5]

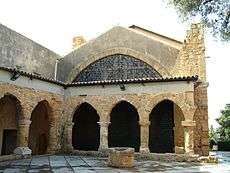

In the meantime, Mascagni's opera Cavalleria rusticana won the Sonzogno competition. It premiered six weeks after Mala Pasqua! at the same theatre. Mascagni's work was a phenomenal success and completely eclipsed Gastaldon's. (By the time of Mascagni's death in 1945, his opera had been performed more than 14,000 times in Italy alone.[6]) There were a few further performances of Mala Pasqua! at the Teatro Morlacchi in Perugia in September 1890 and at the Teatro São Carlos in Lisbon in February 1891, with Theodorini as Carmela on both occasions.[7] After that it sank into oblivion, so much so that some late 20th century reference books claimed that the score was lost. In fact, it was published by Ricordi in 1890 and is held in several libraries in the United States and Europe.[8] On June 22, 2010, Mala Pasqua! received its first performance in 120 years at the Regional Archeology Museum in Agrigento. It was performed in a semi-staged concert format to piano accompaniment as part of a one-day conference entitled "Mala Pasqua! La Cavalleria dimenticata" ("Mala Pasqua! The forgotten Cavalleria"). The production was organized by the Teatro Pirandello in Agrigento and directed by Paolo Panizza. Elena Candia and Piero Lupino Mercuri sang the roles of Carmela and Turiddu with Claudio Onofrio Gallina at the piano and Loredana Russo conducting the Stesicoro Choir.[9]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, April 9, 1890 (Conductor: Vincenzo Lombardi)[10] |

|---|---|---|

| Carmela | soprano | Elena Theodorini |

| Lola | mezzo-soprano | Flora Mariani |

| Turiddu | tenor | Giuseppe Russitano |

| Alfio, Lola's husband | baritone | Aristide Franceschetti[11] |

| Nunzia, Turiddu's mother | soprano | |

| Brasi, a stableman | ||

| Camilla, Brasi's wife |

Synopsis

Setting: A 19th century Sicilian village on Easter Sunday

Turiddu and Lola are lovers. Turiddu's former lover, Carmela, confronts him on Easter morning outside the village church, curses him in a jealous rage, and then tells Lola's husband Alfio about the affair. To preserve his honour, Alfio challenges Turiddu to a knife fight and stabs him to death.

Notes and references

- Rose (August 2009)

- Full text of Verga's letter to Bartocci-Fontana: "M'è grato il suo decidere di prendere ad argomento di un suo libretto per musica la mia Cavalleria rusticana. Devo dirle francamente che il soggetto, così com'è trattato, non sembrami adatto per un dramma musicale. Ma perché ciò non le cambi motivo ad un rifiuto, ben volentieri metto la mia commediola a sua disposizione, lietissimo se Lei ci trova quel che desidera." Quoted in Raya (1990) p. 252

- Scaccetti (2002) p. 491

- Le Ménestrel (April 20, 1890) p. 126

- La Civiltà Cattolica (1890) pp. 345-346

- Schweisheimer (April 1946)

- D'Amico (1975) p. 825

- Hiller (2009) p. 128

- Lorgio (June 23, 2010); Di Bartolo (June 23, 2010)

- Premiere cast from Casaglia (2005), which is in turn based on Frajese (1977)

- Note that in the libretto published prior to the premiere, Antonio Cotogni was listed as Alfio. See Salvagno (2009) p.32. However a review of the premiere published in Le Ménestrel (April 20, 1890) p. 126 confirms that Franceschetti sang the role.

Sources

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Gastaldon". Almanacco Amadeus. Accessed 16 May 2011. (in Italian)

- D'Amico, Silvio (1975). "Teodorini, Elena". Enciclopedia dello spettacolo, Volume 9, p. 825. Unedi-Unione (in Italian)

- Destranges, Etienne (January 23, 1892). "A propos de la Chavalerie rustique". Ouest-Artiste, pp. 56 (in French)

- Di Bartolo, Natalia (June 23, 2010). "Agrigento: Rivive in prima mondiale l'Opera Mala Pasqua di Gastaldon". Teatro.org. Accessed 16 May 2011. (in Italian)

- Fleres, Ugo (April 19, 1890). "Mala Pasqua". Lettere e Arti, Anno II, Numero 14, pp. 218–219 (in Italian)

- Frajese, Vittorio (1977). Dal Costanzi all'Opera: Cronologia completa degli spettacoli, 1880-1960, Vol IV. Edizioni Capitolium (in Italian)

- Hiller, Jonathan (2009). "Verismo Through the Genres, or 'Cavallerie rusticane'—The Delicate Question of Innovation in the Operatic Adaptations of Giovanni Verga's Story and Drama by Pietro Mascagni (1890) and Domenico Monleone (1907)". Carte Italiane, 2(5). Accessed 16 May 2011.

- La Civiltà Cattolica (1890). "Cronaca contemporanea: Cose romane, 1-16 Aprile 1890". (in Italian)

- Le Ménestrel (April 20, 1890). "Nouvelles Diverses: Étranger". Heugel, pp. 125–127 (in French)

- Lorgio, Michele (June 23, 2010). "Mala Pasqua—la Cavalleria dimenticata al Museo Archeologico di Agrigento". Sicilia 24 ore. Accessed 16 May 2011. (in Italian)

- Raya, Gino (1990) Vita di Giovanni Verga. Herder, 1990

- Rose, Scott (August 2009). "Getting It Off Her Chest". Opera News, Vol. 74, No. 2

- Salvagno, Aldo (2009). "Questioni di Cavalleria" in La Fenice prima dell'Opera, 7. Fondazione Teatro La Fenice di Venezia. Accessed 16 May 2011. (in Italian)

- Scaccetti, Maria Paola (2002). "'La Musica Proibita' di Stanislao Gastaldon" in La romanza italiana da salotto, Francesco Sanvitale (ed.). EDT srl. ISBN 88-7063-615-1 (in Italian)

- Schweisheimer, W. (April 1946). "Pietro Mascagni—A Tragic Figure?", The Etude (reprinted on Mascagni.org)

External links

- Photographs of the 2010 revival of Mala Pasqua! in Agrigento

- Full text of Giovanni Verga's 1880 short story "Cavalleria rusticana" (in Italian)

- Full text of "Cavalleria rusticana" translated into English in Under the Shadow of Etna: Sicilian Stories from the Italian of Giovanni Verga (1896)

- Full text of Giovanni Verga's 1884 play Cavalleria rusticana (in Italian)