Magnetic skyrmion

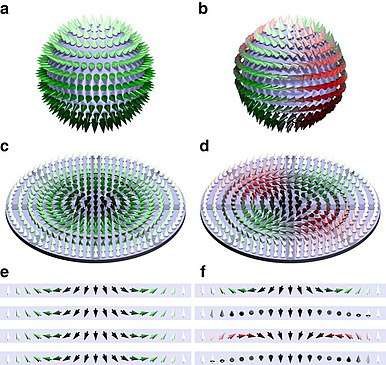

In physics, magnetic skyrmions (occasionally described as 'vortices,'[1] or 'vortex-like'[2] configurations) are quasiparticles[3] which have been predicted theoretically[1][4][5] and observed experimentally[6][7][8] in condensed matter systems. Skyrmions, named after British physicist Tony Hilton Royle Skyrme, can be formed in magnetic materials in their 'bulk' such as in MnSi,[7] or in magnetic thin films.[1][2][9] They can be achiral (Fig. 1 a), or chiral (Fig 1 b) in nature, and may exist both as dynamic excitations[3] or stable or metastable states.[6] Although the broad lines defining magnetic skyrmions have been established de facto, there exist a variety of interpretations with subtle differences.

Most descriptions include the notion of topology - a categorization of shapes and the way in which an object is laid out in space - using a continuous-field approximation as defined in micromagnetics. Descriptions generally specify a non-zero, integer value of the topological index,[10] (not to be confused with the chemistry meaning of 'topological index'). This value is sometimes also referred to as the winding number,[11] the topological charge[10] (although it is unrelated to 'charge' in the electrical sense), the topological quantum number[12] (although it is unrelated to quantum mechanics or quantum mechanical phenomena, notwithstanding the quantization of the index values), or more loosely as the “skyrmion number.”[10] The topological index of the field can be described mathematically as[10]

-

(1)

where is the topological index, is the unit vector in the direction of the local magnetization within the magnetic thin, ultra-thin or bulk film, and the integral is taken over a two dimensional space. (A generalization to a three-dimensional space is possible).. Passing to spherical coordinates for the space ( ) and for the magnetisation ( ), one can understand the meaning of the skyrmion number. In skyrmion configurations the spatial dependence of the magnetisation can be simplified by setting the perpendicular magnetic variable independent of the in-plane angle () and the in-plane magnetic variable independent of the radius ( ). Then the topological skyrmion number reads:

-

(2)

where p describes the magnetisation direction in the origin (p=1 (-1) for ) and W is the winding number. Considering the same uniform magnetisation, i.e. the same p value, the winding number allows to define the skyrmion () with a positive winding number and the antiskyrmion with a negative winding number and thus a topological charge opposite to the one of the skyrmion.

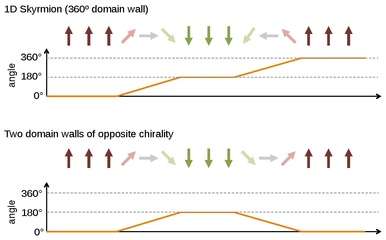

What this equation describes physically is a configuration in which the spins in a magnetic film are all aligned orthonormal to the plane of the film, with the exception of those in one, specific region, where the spins progressively turn over to an orientation that is perpendicular to the plane of the film but anti-parallel to those in the rest of the plane. Assuming 2D isotropy, the free energy of such a configuration is minimized by relaxation towards a state exhibiting circular symmetry, resulting in the configuration illustrated schematically (for a two dimensional skyrmion) in figure 1. In one dimension, the distinction between the progression of magnetization in a 'skyrmionic' pair of domain walls, and the progression of magnetization in a topologically trivial pair of magnetic domain walls, is illustrated in figure 2. Considering this one dimensional case is equivalent to considering a horizontal cut across the diameter of a 2-dimensional hedgehog skyrmion (fig. 1(a)) and looking at the progression of the local spin orientations.

It is worth observing that there are two different configurations which satisfy the topological index criterion stated above. The distinction between these can be made clear by considering a horizontal cut across both of the skyrmions illustrated in figure 1, and looking at the progression of the local spin orientations. In the case of fig. 1(a) the progression of magnetization across the diameter is cycloidal. This type of skyrmion is known as a 'hedgehog skyrmion.' In the case of fig. 1(b), the progression of magnetization is helical, giving rise to what is often called a 'vortex skyrmion.'

Explanation of Stability

The skyrmion magnetic configuration is predicted to be stable because the atomic spins which are oriented opposite those of the surrounding thin-film cannot ‘flip around’ to align themselves with the rest of the atoms in the film, without overcoming an energy barrier. This energy barrier is often ambiguously described as arising from ‘topological protection.’ (See Topological Stability vs. Energy Stability).

Depending on the magnetic interactions existing in a given system, the skyrmion topology can be a stable, meta-stable, or unstable solution when one minimizes the system's free energy.

Theoretical solutions exist for both isolated skyrmions and skyrmion lattices. However, since the stability and behavioral attributes of skyrmions can vary significantly based on the type of interactions in a system, the word 'skyrmion' can refer to substantially different magnetic objects. For this reason, some physicists choose to reserve use of the term 'skyrmion' to describe magnetic objects with a specific set of stability properties, and arising from a specific set of magnetic interactions.

Multiple Definitions of Magnetic Skyrmions

In general, definitions of magnetic skyrmions fall into 2 categories. Which category one chooses to refer to depends largely on the emphasis one wishes to place on different qualities. A first category is based strictly on topology. This definition may seem appropriate when considering topology-dependent properties of magnetic objects, such as their dynamical behavior.[3][14] A second category emphasizes the intrinsic energy stability of certain solitonic magnetic objects. In this case, the energy stability is often (but not necessarily) associated with a form of chiral interaction, which might originate from the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya Interaction (DMI),[10][15][16] or spiral magnetism originating from Double-exchange mechanism (DE) [17] or competing Heisenberg exchange interaction[18].

- When expressed mathematically, definitions in the first category state that magnetic spin-textures with a spin-progression satisfying the condition: where is an integer ≥1, can be qualified as magnetic skyrmions.

- Definitions in the second category similarly stipulate that a magnetic skyrmion exhibits a spin-texture with a spin-progression satisfying the condition: where is an integer ≥1, but further suggest that there must exist an energy term that stabilizes the spin-structure into a localized magnetic soliton whose energy is invariant by translation of the soliton's position in space. (The spatial energy invariance condition constitutes a way to rule out structures stabilized by locally-acting factors external to the system, such as confinement arising from the geometry of a specific nanostructure).

The first set of definitions for magnetic skyrmions is a superset of the second, in that it places less stringent requirements on the properties of a magnetic spin texture. This definition finds a raison d'être because topology itself determines some properties of magnetic spin textures, such as their dynamical responses to excitations.

The second category of definitions may be preferred to underscore intrinsic stability qualities of some magnetic configurations. These qualities arise from stabilizing interactions which may be described in several mathematical ways, including for example by using higher-order spatial derivative terms[4] such as 2nd or 4th order terms to describe a field, (the mechanism originally proposed in particle physics by Tony Skyrme for a continuous field model),[19] [20] or 1st order derivative functionals known as Lifshitz invariants[21]—energy contributions linear in first spatial derivatives of the magnetization—as later proposed by Alexei Bogdanov.[1][22][23][24] (An example of such a 1st order functional is the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya Interaction).[25] In all cases the energy term acts to introduce topologically non-trivial solutions to a system of partial differential equations. In other words, the energy term acts to render possible the existence of a topologically non-trivial magnetic configuration that is confined to a finite, localized region, and possesses an intrinsic stability or meta-stability relative to a trivial homogeneously magnetized ground-state — i.e. a magnetic soliton. An example hamiltonian containing one set of energy terms that allows for the existence of skyrmions of the second category is the following:[2]

-

(2)

where the first, second, third and fourth sums correspond to the exchange, Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya, Zeeman (responsible for the "usual" torques and forces observed on a magnetic dipole moment in a magnetic field), and magnetic Anisotropy (typically magnetocrystalline anisotropy) interaction energies respectively. Note that equation (2) does not contain a term for the dipolar, or 'demagnetizing' interaction between atoms. As in eq. (2), the dipolar interaction is sometimes omitted in simulations of ultra-thin '2 dimensional' magnetic films, because it tends to contribute a minor effect in comparison with the others.

The Role of Topology

Topological Stability vs. Energetic Stability

A non-trivial topology does not in itself imply energetic stability. There is in fact no necessary relation between topology and energetic stability. Hence, one must be careful not to confuse ‘topological stability,’ which is a mathematical concept, with energy stability in real physical systems. Topological stability refers to the idea that in order for a system described by a continuous field to transition from one topological state to another, a rupture must occur in the continuous field, i.e. a discontinuity must be produced. For example, if one wishes to transform a flexible balloon doughnut (torus) into an ordinary spherical balloon, it is necessary to introduce a rupture on some part of the balloon doughnut's surface. Mathematically, the balloon doughnut would be described as 'topologically stable.' However, in physics, the free energy required to introduce a rupture enabling the transition of a system from one ‘topological’ state to another is always finite. For example, it is possible to turn a rubber ballon into flat piece of rubber by poking it with a needle (and popping it!). Thus, while a physical system can be approximately described using the mathematical concept of topology, attributes such as energetic stability are dependent on the system's parameters—the strength of the rubber in the example above—not the topology per se. In order to draw a meaningful parallel between the concept of topological stability and the energy stability of a system, the analogy must necessarily be accompanied by the introduction of a non-zero phenomenological ‘field rigidity’ to account for the finite energy needed to rupture the field’s topology. Modeling and then integrating this field rigidity can be likened to calculating a breakdown energy-density of the field. These considerations suggest that what is often referred to as ‘topological protection,’ or a 'topological barrier,' should more accurately be referred to as a 'topology-related energy barrier,' though this terminology is somewhat cumbersome. A quantitative evaluation of such a topological barrier can be obtained by extracting the critical magnetic configuration when the topological number changes during the dynamical process of a skyrmion creation event. Applying the topological charge defined in a lattice,[26] the barrier height is theoretically shown to be proportional to the exchange stiffness.[27]

Further Observations

It is important to be cognizant of the fact that magnetic =1 structures are in fact not stabilized by virtue of their ‘topology,’ but rather by the field rigidity parameters that characterize a given system. However, this does not suggest that topology plays an insignificant role with respect to energetic stability. On the contrary, topology may create the possibility for certain stable magnetic states to exist, which otherwise could not. However, topology in itself does not guarantee the stability of a state. In order for a state to have stability associated with its topology, it must be further accompanied by a non-zero field rigidity. Thus, topology can be considered a necessary but insufficient condition for the existence of certain classes of stable objects. While this distinction may at first seem pedantic, its physical motivation becomes apparent when considering two magnetic spin configurations of identical topology =1, but subject to the influences of only one differing magnetic interaction. For example, we may consider one spin configuration with, and one configuration without the presence of magnetocrystalline anisotropy, oriented perpendicular to the plane of an ultra-thin magnetic film. In this case, the =1 configuration that is influenced by the magnetocrystalline anisotropy will be more energetically stable than the =1 configuration without it, in spite of identical topologies. This is because the magnetocrystalline anisotropy contributes to the field rigidity, and it is the field rigidity, not the topology, that confers the notable energy barrier protecting the topological state.

Finally, it is interesting to observe that in some cases, it is not the topology which helps =1 configurations to be stable, but rather the converse, as it is the stability of the field (which depends on the relevant interactions) which favors the =1 topology. This is to say that the most stable energy configuration of the field constituents, (in this case magnetic atoms), may in fact be to arrange into a topology which can be described as an =1 topology. Such is the case for magnetic skyrmions stabilized by the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction, which causes adjacent magnetic spins to 'prefer' having a fixed angle between each other (energetically speaking). Note that from a point of view of practical applications this does not alter the usefulness of developing systems with Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction, as such applications depend strictly on the topology [of the skyrmions, or lack thereof], which encodes the information, and not the underlying mechanisms which stabilize the necessary topology.

These examples illustrate why use of the terms 'topological protection' or 'topological stability' interchangeably with the concept of energy stability is misleading, and is liable to lead to fundamental confusion.

Limitations of Applying the Concept of Topology

One must exercise caution when making inferences based on topology-related energy barriers, as it can be misleading to apply the notion of topology—a description which only rigorously applies to continuous fields— to infer the energetic stability of structures existing in discontinuous systems. Giving way to this temptation is sometimes problematic in physics, where fields which are approximated as continuous become discontinuous below certain size-scales. Such is the case for example when the concept of topology is associated with the micromagnetic model—which approximates the magnetic texture of a system as a continuous field—and then applied indiscriminately without consideration of the model's physical limitations (i.e. that it ceases to be valid at atomic dimensions). In practice, treating the spin textures of magnetic materials as vectors of a continuous field model becomes inaccurate at size-scales on the order of < 2 nm, due to the discretization of the atomic lattice. Thus, it is not meaningful to speak of magnetic skyrmions above these size-scales.

Practical Applications

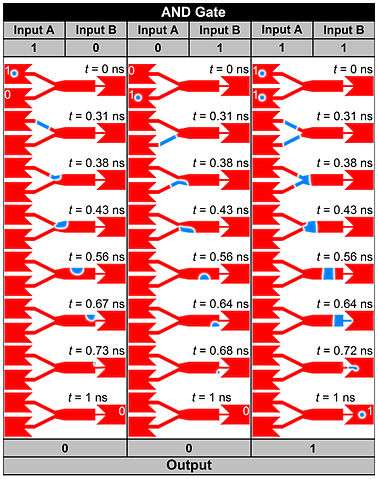

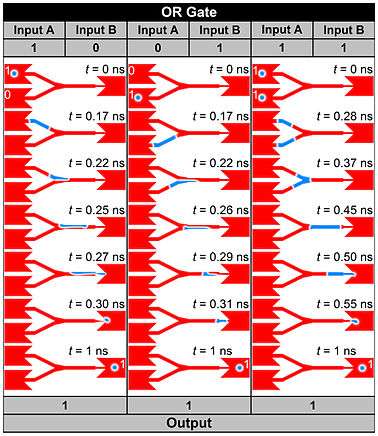

Magnetic skyrmions are anticipated to allow for the existence of discrete magnetic states which are significantly more energetically stable (per unit volume) than their single-domain counterparts. For this reason, it is envisioned that magnetic skyrmions may be used as bits to store information in future memory and logic devices, where the state of the bit is encoded by the existence or non-existence of the magnetic skyrmion. The dynamical magnetic skyrmion exhibits strong breathing which opens the avenue for skyrmion-based microwave applications.[29] Simulations also indicate that the position of magnetic skyrmions within a film/nanotrack may be manipulated using spin currents [9] or spin waves.[30] Thus, magnetic skyrmions also provide promising candidates for future racetrack-type in-memory logic computing technologies.[9][28][31][32]

References

- A.N. Bogdanov; U.K. Rossler (2001). "Chiral Symmetry Breaking in Magnetic Thin Films and Multilayers". Physical Review Letters. 87 (3): 037203. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..87c7203B. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.87.037203. PMID 11461587.

- J. Iwasaki; M. Mochizuki; N. Nagaosa (2013). "Current-induced skyrmion dynamics in constricted geometries". Nature Nanotechnology. 8 (10): 742–747. arXiv:1310.1655. Bibcode:2013NatNa...8..742I. doi:10.1038/nnano.2013.176. PMID 24013132.

- S.L. Sondhi; A Karlhede; S.A. Kivelson (1993). "Skyrmions and the crossover from the integer to fractional quantum Hall effect at small Zeeman energies". Physical Review B. 47 (24): 16419–16426. Bibcode:1993PhRvB..4716419S. doi:10.1103/physrevb.47.16419. PMID 10006073.

- U.K. Rossler; A.N. Bogdanov; C. Pfleiderer (2006). "Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals". Nature Letters. 442 (7104): 797–801. arXiv:cond-mat/0603103. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..797R. doi:10.1038/nature05056.

- B. Dupe; M. Hoffmann; C. Paillard; S. Heinze (2014). "Tailoring magnetic skyrmions in ultra-thin transition metal films". Nature Communications. 5: 4030. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4030D. doi:10.1038/ncomms5030. PMID 24893652.

- N. Romming; et al. (2013). "Writing and deleting single magnetic skyrmions". Science. 341 (6146): 636–639. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..636R. doi:10.1126/science.1240573. PMID 23929977.

- S. Muhlbauer; B. Binz; F. Jonietz; C. Pfleiderer; A. Rosch; A Neubauer; R. Georgii; P. Boni (2009). "Skyrmion Lattice in a Chiral Magnet". Science. 323 (5916): 915–919. arXiv:0902.1968. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..915M. doi:10.1126/science.1166767. PMID 19213914.

- Hsu, Pin-Jui; Kubetzka, André; Finco, Aurore; Romming, Niklas; Bergmann, Kirsten von; Wiesendanger, Roland (2016). "Electric-field-driven switching of individual magnetic skyrmions". Nature Nanotechnology. 12 (2): 123–126. arXiv:1601.02935. Bibcode:2017NatNa..12..123H. doi:10.1038/nnano.2016.234. PMID 27819694.

- A. Fert; V. Cros; J. Sampaio (2013). "Skyrmions on the track". Nature Nanotechnology. 8 (3): 152–156. Bibcode:2013NatNa...8..152F. doi:10.1038/nnano.2013.29. PMID 23459548.

- S. Heinze; K. v. Bergmann; M. Menzel; J. Brede; A. Kubetzka; R. Wiesendanger; G. Bihlmayer; S. Blügel (2011). "Spontaneous atomic-scale magnetic skyrmion lattice in two dimensions". Nature Physics. 7 (9): 713–718. Bibcode:2011NatPh...7..713H. doi:10.1038/nphys2045.

- K. v. Bergmann; A. Kubetzka; O. Pietzsch; R. Wiesendanger (2014). "Interface-induced chiral domain walls, spin spirals and skyrmions revealed by spin-polarized scanning tunneling microscopy". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 26 (39): 394002. Bibcode:2014JPCM...26M4002V. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/26/39/394002.

- M. Finazzi; M. Savoini; A.R. Khorsand; A. Tsukamoto; A. Itoh; L. Duo; A. Kirilyuk; Th. Rasing & M. Ezawa (2013). "Laser-Induced Magnetic Nanostructures with Tunable Topological Properties". Physical Review Letters. 110 (17): 177205. arXiv:1304.1754. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110q7205F. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.110.177205. PMID 23679767.

- Markus Hoffmann; Bernd Zimmermann; Gideon P. Müller; Daniel Schürhoff; Nikolai S. Kiselev; Christof Melcher & Stefan Blügel (2013). "Antiskyrmions stabilized at interfaces by anisotropic Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions". Nature Communications. 8 (308). arXiv:1702.07573. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00313-0.

- Brey, L.; Fertig, H. A.; Côté, R.; MacDonald, A. H. (1997). "Skyrmions in the quantum hall effect". Lecture Notes in Physics. 478: 275–283. doi:10.1007/bfb0104643. ISBN 978-3-540-62476-9.

- N. S. Kiselev; A. N. Bogdanov; R. Schafer; U.K. Rossler (2011). "Chiral skyrmions in thin magnetic films: new objects for magnetic storage technologies?". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 44 (39): 392001. arXiv:1102.2726. Bibcode:2011JPhD...44M2001K. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/44/39/392001.

- N. Nagaosa; Y. Tokura (2013). "Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions". Nature Nanotechnology. 8 (12): 899–911. Bibcode:2013NatNa...8..899N. doi:10.1038/nnano.2013.243. PMID 24302027.

- Azhar, Maria; Mostovoy, Maxim (2017). "Incommensurate Spiral Order from Double-Exchange Interactions". Physical Review Letters. 118 (2): 027203. arXiv:1611.03689. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.118b7203A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.027203. PMID 28128593.

- Leonov, A. O.; Mostovoy, M. (2015-09-23). "Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet". Nature Communications. 6: 8275. arXiv:1501.02757. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8275L. doi:10.1038/ncomms9275. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4667438. PMID 26394924.

- T.H. Skyrme (1961). "A non-linear field theory". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 260 (1300): 127–138. Bibcode:1961RSPSA.260..127S. doi:10.1098/rspa.1961.0018.

- Ulrich K. Rossler; Andrei A. Leonov; Alexei N. Bogdanov (2010). "Skyrmionic textures in chiral magnets". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 200 (2): 022029. arXiv:0907.3651. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/200/2/022029.

- L. D. Landau & E. M. Lifshitz (1997). "Statistical Physics. Course of Theoretical Physics". 5. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - A.N. Bogdanov; D.A. Yablonskii (1989). "Thermodynamically stable 'vortices' in magnetically ordered crystals. The mixed state of magnets". Sov. Phys. JETP. 68: 101–103.

- A. Bogdanov; A. Hubert (1994). "Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals". J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 138 (3): 255–269. Bibcode:1994JMMM..138..255B. doi:10.1016/0304-8853(94)90046-9.

- A. Bogdanov (1995). "New localized solutions of the nonlinear field-equations". JETP Lett. 62: 247–251.

- I.E. Dzyaloshinskii (1964). "Theory of Helicoidal Structures in Antiferromagnets. I. Nonmetals". Sov. Phys. JETP. 19: 960.

- Berg, B.; Lüscher, M. (1981-08-24). "Definition and statistical distributions of a topological number in the lattice O(3) σ-model". Nuclear Physics B. 190 (2): 412–424. Bibcode:1981NuPhB.190..412B. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(81)90568-X.

- Yin, Gen (2016-01-01). "Topological charge analysis of ultrafast single skyrmion creation". Physical Review B. 93 (17): 174403. arXiv:1411.7762. Bibcode:2016PhRvB..93q4403Y. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.93.174403.

- X.C. Zhang; M. Ezawa; Y. Zhou (2014). "Magnetic skyrmion logic gates: conversion, duplication and merging of skyrmions". Scientific Reports. 5: 9400. arXiv:1410.3086. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E9400Z. doi:10.1038/srep09400. PMC 4371840. PMID 25802991.

- Y. Zhou; E. Iacocca; A.A. Awad; R.K. Dumas; F.C. Zhang; H.B. Braun; J. Akerman (2015). "Dynamically stabilized magnetic skyrmions". Nature Communications. 6: 8193. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8193Z. doi:10.1038/ncomms9193. PMC 4579603. PMID 26351104.

- X.C. Zhang; M. Ezawa; D. Xiao; G.P. Zhao; Y.W. Liu; Y. Zhou (2015). "All-magnetic control of skyrmions in nanowires by a spin wave". Nanotechnology. 26 (22): 225701. arXiv:1504.00409. Bibcode:2015Nanot..26v5701Z. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/26/22/225701. PMID 25965121.

- Y. Zhou; M. Ezawa (2014). "A reversible conversion between a skyrmion and a domain-wall pair in a junction geometry". Nature Communications. 5: 4652. arXiv:1404.3350. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.4652Z. doi:10.1038/ncomms5652. PMID 25115977.

- X.C. Zhang; Y. Zhou; M. Ezawa; G. P. Zhao; W.S. Zhao (2015). "Magnetic skyrmion transistor: skyrmion motion in a voltagegated nanotrack". Scientific Reports. 5: 11369. Bibcode:2015NatSR...511369Z. doi:10.1038/srep11369. PMC 4471904. PMID 26087287.