Maenad

In Greek mythology, maenads (/ˈmiːnædz/; Ancient Greek: μαϊνάδες [maiˈnades]) were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of the Thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name literally translates as "raving ones". Maenads were known as Bassarids, Bacchae /ˈbækiː/, or Bacchantes /ˈbækənts, bəˈkænts, -ˈkɑːnts/ in Roman mythology after the penchant of the equivalent Roman god, Bacchus, to wear a bassaris or fox skin.

Often the maenads were portrayed as inspired by Dionysus into a state of ecstatic frenzy through a combination of dancing and intoxication.[1] During these rites, the maenads would dress in fawn skins and carry a thyrsus, a long stick wrapped in ivy or vine leaves and tipped with a pine cone. They would weave ivy-wreaths around their heads or wear a bull helmet in honor of their god, and often handle or wear snakes.[2]

These women were mythologized as the "mad women" who were nurses of Dionysus in Nysa. Lycurgus "chased the Nurses of the frenzied Dionysus through the holy hills of Nysa, and the sacred implements dropped to the ground from the hands of one and all, as the murderous Lycurgus struck them down with his ox-goad".[3] They went into the mountains at night and practiced strange rites.[4]

According to Plutarch's Life of Alexander, maenads were called Mimallones and Klodones in Macedon, epithets derived from the feminine art of spinning wool.[5] Nevertheless, these warlike parthenoi ("virgins") from the hills, associated with a Dionysios pseudanor "fake male Dionysus", routed an invading enemy.[6] In southern Greece they were described as Bacchae, Bassarides, Thyiades, Potniades,[7] and other epithets.[8]

The term maenad has come to be associated with a wide variety of women, supernatural, mythological, and historical,[9] associated with the god Dionysus and his worship.

In Euripides' play The Bacchae, maenads of Thebes murder King Pentheus after he bans the worship of Dionysus. Dionysus, Pentheus' cousin, himself lures Pentheus to the woods, where the maenads tear him apart. His corpse is mutilated by his own mother, Agave, who tears off his head, believing it to be that of a lion. A group of maenads also kill Orpheus.[10]

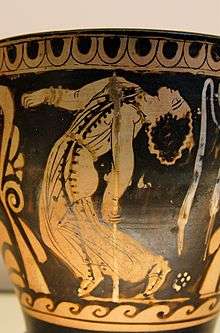

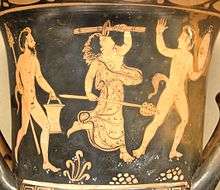

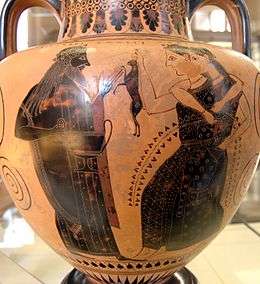

In ceramic art, the frolicking of Maenads and Dionysus is often a theme depicted on kraters, used to mix water and wine. These scenes show the maenads in their frenzy running in the forests, often tearing to pieces any animal they happen to come across.

German philologist Walter Friedrich Otto writes:

The Bacchae of Euripides gives us the most vital picture of the wonderful circumstance in which, as Plato says in the Ion, the god-intoxicated celebrants draw milk and honey from the streams. They strike rocks with the thyrsus, and water gushes forth. They lower the thyrsus to the earth, and a spring of wine bubbles up. If they want milk, they scratch up the ground with their fingers and draw up the milky fluid. Honey trickles down from the thyrsus made of the wood of the ivy, they gird themselves with snakes and give suck to fawns and wolf cubs as if they were infants at the breast. Fire does not burn them. No weapon of iron can wound them, and the snakes harmlessly lick up the sweat from their heated cheeks. Fierce bulls fall to the ground, victims to numberless, tearing female hands, and sturdy trees are torn up by the roots with their combined efforts.[11]

Cult worship

Bacchanalia

Cultist rites associated with worship of the Greek god of wine, Dionysus (or Bacchus in Roman mythology), were characterized by maniacal dancing to the sound of loud music and crashing cymbals, in which the revelers, called Bacchantes, whirled, screamed, became drunk and incited one another to greater and greater ecstasy. The goal was to achieve a state of enthusiasm in which the celebrants’ souls were temporarily freed from their earthly bodies and were able to commune with Bacchus/Dionysus and gain a glimpse of and a preparation for what they would someday experience in eternity. The rite climaxed in a performance of frenzied feats of strength and madness, such as uprooting trees, tearing a bull (the symbol of Dionysus) apart with their bare hands, an act called sparagmos, and eating its flesh raw, an act called omophagia. This latter rite was a sacrament akin to communion in which the participants assumed the strength and character of the god by symbolically eating the raw flesh and drinking the blood of his symbolic incarnation. Having symbolically eaten his body and drunk his blood, the celebrants became possessed by Dionysus.

Priestesses of Dionysus

"Maenads" are found in later references as priestesses of the Dionysian cult. In the third century BC, when an Asia Minor city wanted to create a maenadic cult of Dionysus, the Delphic Oracle bid them to send to Thebes for both instruction and three professional maenads, stating, "Go to the holy plain of Thebes so that you may get maenads who are from the family of Ino, daughter of Cadmus. They will give to you both the rites and good practices and they will establish dance groups (thiasoi) of Bacchus in your city."

Myths

Dionysus came to his birthplace, Thebes, where neither Pentheus, his cousin who was now king, nor Pentheus’ mother Agave, Dionysus’ aunt (Semele's sister) acknowledged his divinity. Dionysus punished Agave by driving her insane, and in that condition, she killed her son and tore him to pieces. From Thebes, Dionysus went to Argos where all the women except the daughters of King Proetus joined in his worship. Dionysus punished them by driving them mad, and they killed the infants who were nursing at their breasts. He did the same to the daughters of Minyas, King of Orchomenos in Boetia, and then turned them into bats.

According to Opian, Dionysus delighted, as a child, in tearing kids into pieces and bringing them back to life again. He is characterized as "the raging one" and "the mad one" and the nature of the maenads, from which they get their name, is, therefore, his nature.[12]

Once during a war in the middle of the third century BC, the entranced Thyiades (maenads) lost their way and arrived in Amphissa, a city near Delphi. There they sank down exhausted in the market place and were overpowered by a deep sleep. The women of Amphissa formed a protective ring around them and when they awoke arranged for them to return home unmolested.

On another occasion, the Thyiades were snowed in on Parnassos and it was necessary to send a rescue party. The clothing of the men who took part in the rescue froze solid. It is unlikely that the Thyiades, even if they wore deerskins over their shoulders, were ever dressed more warmly than the men.[13]

Nurses and nymphs

In the realm of the supernatural is the category of nymphs who nurse and care for the young Dionysus, and continue in his worship as he comes of age. The god Hermes is said to have carried the young Dionysus to the nymphs of Nysa.

In another myth, when his mother, Semele, is killed, the care of young Dionysus falls into the hands of his sisters, Ino, Agave, and Autonoe, who later are depicted as participating in the rites and taking a leadership role among the other maenads.

Resisters to the new religion

The term "maenads" also refers to women in mythology who resisted the worship of Dionysus and were driven mad by him, forced against their will to participate in often horrific rites. The doubting women of Thebes, the prototypical maenads or "mad women", left their homes to live in the wilds of the nearby mountain Cithaeron. When they discovered Pentheus spying on them, dressed as a maenad, they tore him limb from limb.[14]

This also occurs with the three daughters of Minyas, who reject Dionysus and remain true to their household duties, becoming startled by invisible drums, flutes, cymbals, and seeing ivy hanging down from their looms. As punishment for their resistance, they become madwomen, choosing the child of one of their number by lot and tearing it to pieces, as the women on the mountain did to young animals. A similar story with a tragic end is told of the daughters of Proetus.

Voluntary revelers

Not all women were inclined to resist the call of Dionysus, however. Maenads, possessed by the spirit of Dionysus, traveled with him from Thrace to mainland Greece in his quest for the recognition of his divinity. Dionysus was said to have danced down from Parnassos accompanied by Delphic virgins, and it is known that even as young girls the women in Boeotia practiced not only the closed rites but also the bearing of the thyrsus and the dances.

The possible foundation myth is the very ancient festival called Agrionia. According to Greek authors like Plutarchos women followers of Dyonisos went in search of him and when they could not find him prepared a feast. A feature of this festival was recorded by Plutarch. A priest would chase a group of virgins down with a sword. These women were supposed to be descendants of the women who sacrificed their son in the name of Dionysios. The priest caught one of the woman and executed her. This type of human sacrifice was later omitted from the festival. Eventually the women would be freed from the madness and return to Thebes and their usual lives, but for the time of the festival they would have had an intense ecstatic experience. The Agrionia was celebrated in several Greek cities, but especially in Boeotia. Each Boeotian city had its own distinct foundation myth for it, but the pattern was much the same: the arrival of Dionysus, resistance to him, flight of the women to a mountain, the killing of Dionysus’ persecutor, and eventual reconciliation with the god.

Art

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_73_x_54_cm_DSC05359...jpg)

Maenads have been depicted in art as erratic and frenzied women enveloped in a drunken rapture, the most obvious example being that of Euripides’ play The Bacchae. His play, however, is not a study of the cult of Dionysus or the effects of this religious hysteria of these women. The maenads have often been interpreted in art in this way. To understand the play of Euripides one must only know about the religious ecstasy called Dionysiac, the most common moment maenads are displayed in art. In Euripides' play and other art forms and works, the Dionysiac only needs to be understood as the frenzied dances of the god which are direct manifestations of euphoric possession and that these worshipers, sometimes by eating the flesh of a man or animal who has temporarily incarnated the god, come to partake of his divinity.

In addition to Euripides' The Bacchae, depictions of maenads are often found on both red and black figure Greek pottery, statues, and jewelry. Also, fragments of reliefs of female worshipers of Dionysus have been discovered at Corinth.[15] Mark W. Edwards in his paper "Representation of Maenads on Archaic Red-Figure Vases" traces the evolution of maenad depictions on red figure vases. Edwards distinguishes between "nymphs" which appear earlier on Greek pottery and "maenads" which are identified by their characteristic fawnskin or nebris and often carry snakes in their hands. However, Edwards does not consider the actions of the figures on the pottery to be a distinguishing characteristic for differentiation between maenads and nymphs. Rather, the differences or similarities in their actions are more striking when comparing black figure and red figure pottery, as opposed to maenads and nymphs.[16]

Maenad carrying a hind, fragment of an Attic red figure cup ca. 480BC Louvre Museum.

Maenad carrying a hind, fragment of an Attic red figure cup ca. 480BC Louvre Museum. Ancient Greek terracotta statuette of a dancing maenad, 3rd century BC, from Taranto. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Ancient Greek terracotta statuette of a dancing maenad, 3rd century BC, from Taranto. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Statue of a sleeping Maenad, lying on a panther skin spread on a rocky surface; the type is known as the reclining Hermaphrodite; Pentelic marble; found at the south of the Athenian Acropolis; Hadrianic time (117-138 AD), follows a classical trend in the attic art; National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Statue of a sleeping Maenad, lying on a panther skin spread on a rocky surface; the type is known as the reclining Hermaphrodite; Pentelic marble; found at the south of the Athenian Acropolis; Hadrianic time (117-138 AD), follows a classical trend in the attic art; National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Ring with the engraved representation of a maenad. Ancient Greek artwork, 3rd–2nd century BC. Louvre, Paris.

Ring with the engraved representation of a maenad. Ancient Greek artwork, 3rd–2nd century BC. Louvre, Paris. A Roman fresco from Pompeii showing a Maenad in silk dress, 1st century AD

A Roman fresco from Pompeii showing a Maenad in silk dress, 1st century AD Roman fresco of a maenad from the Casa del Criptoportico in Pompeii.

Roman fresco of a maenad from the Casa del Criptoportico in Pompeii. Dance of the Maenads by Andries Cornelis Lens

Dance of the Maenads by Andries Cornelis Lens A Bacchante, by John Reinhard Weguelin

A Bacchante, by John Reinhard Weguelin A Bacchante, by William Etty

A Bacchante, by William Etty Bacchante by Frederick William MacMonnies, 1894. Brooklyn Museum

Bacchante by Frederick William MacMonnies, 1894. Brooklyn Museum Female Bacchante by Royal Worcester, 1898. Brooklyn Museum

Female Bacchante by Royal Worcester, 1898. Brooklyn Museum Maenad and the Panther by Ernst Julius Hähnel 1886, Albertinum, Dres

Maenad and the Panther by Ernst Julius Hähnel 1886, Albertinum, Dres

Later culture

Books and comics

A maenad appears in Percy Bysshe Shelley's poem "Ode to the West Wind".

In Ivan Turgenev's novella First Love, Bacchantes are used symbolically in a dream of Princess Zinaida.[17]

Maenads, along with Bacchus and Silenus, appear in C. S. Lewis' Prince Caspian. They are portrayed as wild, fierce girls who dance and perform somersaults.

Maenadism is referenced by the 2013 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Canadian Alice Munro, in her collection of short stories titled Runaway (2004). No explanation is offered for the significance of this reference, but the independence and power of this cultist group of women, would seem to be a metaphor for the autonomy needed by women in the modern age, to better stake out a claim against an oppressive patriarchy; a claim many women seem to be all too willing to forgo.

Poul Anderson's "Goat Song" depicts a far-future utopia where all human activity has been "optimized" by the artificial intelligence SUM. To placate their fear of dying, citizens of this utopia are promised resurrection using DNA and memory records collected by bracelets that everyone wears. Rebelling against nonhuman control, one citizen called Harper (identified with Orpheus) awakens atavism in a group of women who spend holidays in the wild living as maenads.

The short story "Las Ménades" by Julio Cortázar, originally published in Final del juego in 1956, describes a concert in which the narrator does not react emotionally to the music, but a number of women are overwhelmed with emotion and surge onto the stage, overtaking the conductor and musicians.

In Piers Anthony's Xanth series, the maenads are depicted as women frenzied with bloodlust. The maenads were temporarily quelled by Magician Grey as his talent is nullification of magic. In combination with a large python protecting the Oracle's Cave, the maenads presence is to protect Mount Parnassus (see "Man from Mundania").

In Fables & Reflections, the seventh volume of Neil Gaiman's comic series The Sandman, the maenads feature in the story Orpheus, in which they gruesomely murder the titular character after he refuses to cavort with them (echoing the events of the actual Greek myth of Orpheus).

In the horror novel Dominion by Bentley Little, maenads are eventually revealed as the main antagonists for the first half of the story, during which they tear their victims to shreds and conspire to reawaken Dionysus.

The Buffy the Vampire Slayer novel Go Ask Malice: A Slayer's Diary depicts maenads as corrupted human beings in service of the ancient and powerful Greek vampire Kakistos.[18]

The maenads appear in Rick Riordan's The Demigod Diaries where they are the principal enemies in the story "Leo Valdez and the Quest for Buford". While looking for the automaton table, Buford, Leo, Jason, and Piper run into the maenads, who are searching for Dionysus. They chase Leo and Piper into Bunker 9 and are subsequently captured in a golden net.

In Sailor Moon, the two priestesses guarding the shrine of Elysium deep within the Earth (the most sacred place of the Golden Kingdom) are called maenads.[19] However, they have nothing in common with the mythological maenads: they are not frenzied or dangerous, their number is stable, don't travel (in fact they seem to be forbidden from leaving), and are not in anyway connected with Dionysus/Bacchus (no reference to this god is ever made in the entire franchise). They are instead connected with a character named after the Greek personification of the sun (Helios).

The short story "Last Call" of Jim Butcher's The Dresden Files features a maenad as a primary antagonist.

_-_Bacchante_(1894).jpg)

Opera and television

The Bassarids (composed 1964–65, premiered 1966), to a libretto by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman, is the most famous opera composed by Hans Werner Henze.

Charlaine Harris' The Southern Vampire Mysteries novels and its television adaptation, HBO's True Blood (2nd season, aired in summer 2009), feature maenads in the characters of Callisto and Maryann, respectively. In the show, Maryann wishes to sacrifice Sam Merlotte in hopes of summoning her god, Dionysus.[20] Maryann is portrayed by Michelle Forbes.

Maenads appear in "A Girl By Any Other Name", an episode of Atlantis. They also appear in season 4 of The Magicians, where they party alongside Bacchus and nurse him through his magical ailments.

Real life

Maenads are the adopted symbol of Tetovo in North Macedonia, depicted prominently of the city's coat of arms. The inclusion of maenad imagery dates to 1932 when a small statuette of a maenad, dating to the 6th century BC, was found in the city. The "Tetovo Maenad" was featured on the reverse of a Macedonian 5000 denar banknote issued in 1996.[21]

The Japanese cosmetics company Nippon Menard Cosmetic Co. is named after them.

References

- Wiles, David (2000). Greek Theater Performance: An Introduction. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Abel, Ernest L. (2006). Intoxication in Mythology: A Worldwide Dictionary of Gods, Rites, Intoxicants, and Place. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland & Co., Inc.

- Homer, Iliad, VI.130ff, in E.V. Rieu's translation.

- Lever, Katherine (1956). The Art of Greek Comedy.

- According to Grace Harriet Macurdy, "Klodones, Mimallones and Dionysus Pseudanor," The Classical Review 27.6 (September 1913), pp. 191-192, and Troy and Paeonia. With Glimpses of Ancient Balkan History and Religion, 1925, p. 166.

- According to the second-century CE Macedonian military writer Polyaenus, IV.1; Polyaenus gives a fanciful etymology..

- Potnia means "lady" or "mistress".

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (1922). "The Maenads". Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, 3rd ed. p.388-400.

- Jane Ellen Harrison remarked of the 19th-century (male) classicists, "so persistent is the dislike to commonplace fact, that we are repeatedly told that the maenads are purely mythological creations and that the maenad orgies never appear historically in Greece." Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, 3rd ed. (1922). p.388

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Library and Epitome, 1.3.2. "Orpheus also invented the mysteries of Dionysus, and having been torn in pieces by the maenads he is buried in Pieria."

- Otto, Walter F. (1965). Dionysus: Myth and Cult. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p.96

- Otto, Walter F. (1965). Dionysus: Myth and Cult. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p.135

- Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life; translated from the German by Ralph Manheim; Bollingen Series LXV 2; Princeton University Press 1976. pg. 220.

- Euripides, The Bacchae

- Richardson, Rufus B. "A Group of Dionsiac Sculptures from Corinth". American Journal of Archaeology 8, no.3 (July–September 1904): 288-296.

- Edwards, Mark W. "Representation of Maenads on Archaic Red-Figure Vases". The Journal of Hellenistic Studies 80 (1960): 78-87.

- Turgenev, Ivan Sergeyevich. "Excerpt from First Love". Wiztrit.

- Walton, J. Michael, Found in translation: Greek drama in English, Cambridge University Press, 2006. Confer p. 128.

- Takeuchi, Naoko (March 6, 1996). "Act 40". Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon Volume 14. Kodansha. ISBN 978-4-06-178826-8.

- TVguide.com

- National Bank of the Republic of Macedonia. Macedonian currency. Banknotes in circulation: 5000 Denars Archived 2009-04-27 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 30 March 2009.

Further reading

- Abel, Ernest L. (2006). Intoxication in Mythology: A Worldwide Dictionary of Gods, Rites, Intoxicants, and Place. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland & Co., Inc., Publishers.

- Edwards, Mark W. "Representation of Maenads on Archaic Red-Figure Vases." The Journal of Hellenistic Studies 80 (1960): 78-87.

- Manheim, Ralph (translator) (1976). Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life. Bollingen Series LXV 2; Princeton University Press.

- Mikalson, Jon D. (2005). Ancient Greek Religion. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Morford, Mark P.O., and Lenardon, Robert J. (2003). Classical Mythology, 7th ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Otto, Walter F. (1965). Dionysus: Myth and Cult. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Richardson, Rufus B. "A Group of Dionsiac Sculptures from Corinth." American Journal of Archaeology 8, no.3 (July- September 1904): 288-296.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Background and Images for the Bacchae