Macropis nuda

Macropis nuda is a ground nesting, univoltine bee native to northern parts of North America. Thus, this species cocoons as pupae and hibernates over the winter. The species is unique as it is an oligolectic bee, foraging mainly for floral oils from Primulaceae of the genus Lysimachia.[1]

| Macropis nuda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female | |

| |

| Male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Melittidae |

| Genus: | Macropis |

| Species: | M. nuda |

| Binomial name | |

| Macropis nuda (Provancher, 1882) | |

| |

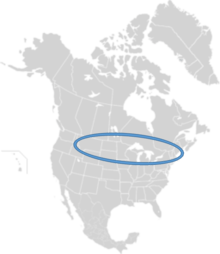

| Range of M. nuda | |

Taxonomy

Macropis nuda is a member of the family Melittidae and the order Hymenoptera. All species of the genus Macropis are oligolectic, as females forage for loosestrife plant oil to line their nests and provision to their eggs. Macropis bees are commonly referred to as oil-bees, as they are the main pollinators of oil-plants such as plants of the genus Lysimachia.[1]

Identification and differentiation

Both males and females of M. nuda are roughly 7-7.5mm in length.

Females

The head, thorax, and abdomen of M. nuda females are a dark black. Females have dense white scopa on their posterior tibiae that are foraging adaptations used for collecting and carrying floral oils and pollen.[1] These scopae are distinct from other bees as they use capillary action to hold floral oils.[2]

Males

Similar to females, the head, thorax and abdomen of M. nuda males are dark black. Males are differentiated by having much less scopa, or hair, on their posterior tibiae. Males are characterized by yellow markings on their heads, the broad plate on the front of the head being completely yellow.[1]

Distribution and habitat

M. nuda is native to North America. As it is an oligolectic bee, it is found where plants of the genus Lysimachia grow. M. nuda can be found in parts of Canada, Montana, Idaho, Colorado, Maine, New Jersey and New York.[3]

Nesting

M. nuda females are solitary and build their nests in the ground each season, but may reuse old nests. Nests are inhabited by a single female and no males.[4]

Nest site

M. nuda females are particular about their nest sites as their nests are in the ground. Females will make their nests in shady areas of drier, sandy-loam textured soil.[5] Nests are typically near the loosestrife flowers from which females collect oil and pollen. Though females are solitary and build their own nests, nests will be found in aggregates due to the criteria of nest site.[2]

Nest description

M. nuda nests are compact and rather shallow, as the deepest cells are only up to 6.5mm below the surface.[4] Entrances of nests are usually concealed by dried leaves, twigs, rocks, or low-growing plants. Burrows are approximately 3.0-3.5mm in diameter and are coated with a waterproof lining created from the floral oils collected by the female. The lining maintains homeostatic humidity conditions for offspring. Cells are also coated with this waterproof lining to keep them dry while offspring are in their cocoons during the winter.[4]

Life cycle

M. nuda is a solitary bee species. Females make their own nests in the ground, and are univoltine, having only one brood during a mating season as offspring hibernate in the nest until they mature the next season. Males and females spend the winter in cocoons as mature pupae, and recommence development in the spring as the temperature increases.[6] Once emerged, young females will either find a new nesting site or commandeer an old nest.[7]

Development

Larvae rapidly develop into pupae within 10 days, feeding on a provision that is a mixture of floral oil and pollen.[4]

Egg

A female M. nuda digs a cell, then lines it with oils from Lysimachia plants. The female then provisions the cell with a mixture of floral oil and pollen from the Lysimachia plant. She then lays a single, white colored egg in the cell before closing it with soil. The larval feeding period lasts approximately 10–14 days, after which they are pupae and begin to spin cocoons.[4]

Cocoon

After the larval feeding period, pupae spin the cocoons in which they will hibernate until the next spring. Cocoons completely occupy the cells, and strongly adhere to the sides of the cell, but not the closure.[4] There is a small hole near the apex of the cocoon, opening to the soil closure of the cell. This allows exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide as the waxy oil coating the cell and the silk of the cocoon does not allow for gas movement. Not only does the cocoon allow safety from the cold of the winter, it may also serve as a barricade to protect against parasites and predators.[4]

Emergence

Macropis species are protandrous, as male bees emerge from their cocoons 1–2 weeks before females emerge.[7] Because M. nuda males emerge before females, they also reach sexual maturity earlier. Females reach sexual maturity shortly after they emerge when they begin constructing their nests.[7]

Behavior

Macropis nuda behavior of males and females in regards to foraging and mating.

Plant-pollinator communication

Females will feed themselves with nectar of a variety of flowers, but will only use oil and pollen from Lysimachia plants for provisioning. Females are found around Lysimachia plants in times of full sun and collect oil and pollen simultaneously.[2] Because Lysimachia plants produce fatty oils in the place of nectar, oil-bees like Macropis nuda are the main pollinators of these plants. Little was known about the chemical communication for how Macropis bees find Lysimachia plants until a 2007 study of Lysimachia chemical indicators.[8] Flower-specific chemicals were identified by gas chromatography, then Macropis species were used to test if these flower-specific chemicals were the source of attraction. The identified compounds in Lysimachia plants were found to be strong attractors of Macropis bees, and are seldom found in other plants.[8] The interaction between floral oil secreting plants and oil-collecting bees is one of the most specialized of all pollinating systems. A 2015 study identified diacetin, a volatile acteylated glycerol, as a key volatile used by oil-collecting bees like M. nuda to locate food sources. Diacetin is the first demonstrated private form of communication between plant and pollinator.[9]

Male behavior

Unlike females, male Macropis nuda do not rely on Lysimachia plants for their oils. The daily activity of patrolling males begins near nest aggregates, then progresses to nearby flowers where both males and females feed themselves on a variety of nectars.[10] Males only collect nectar, but will travel to Lysimachia plants for mating opportunities where females collect floral oils. Males attempt to mate by directly pouncing on females, regardless of whether the female is carrying pollen or oil.[2] Males are not allowed into a females nest, and rest on flowers while females will sleep in their nests.[4]

Mating behavior

Macropis nuda does not have any clear mating rituals. There has been no observed scent marking,[2] and males and females do not produce any kind of sound to attract one another like other solitary bees such as Meganomia.[11] Mating appears to be quick and random, where males patrol Lysimachia plants and pounce on females. Females reject males that pounce for mating by swiftly kicking with their hind legs.[2] If receptive, a pair will hold together and fall from a flower, dislodging in the air or landing on the ground. The act is quick and takes around 1–2 seconds to complete. Copulation has only been observed near the Lysimachia plants, never near nest sites.

Parasites

M. nuda is parasitized by Epeoloides pilosulus, commonly referred to as a Macropis Cuckoo Bee.[12] The common name of this cleptoparasite refers to how this species of bee invades a host nest and lays its eggs in a host cell. Macropis Cuckoo Bee larvae cocoon and hibernate similarly to M. nuda. The parasitic bee larvae will receive provisions from the M. nuda mother as if they were her own offspring. The parasitic bee is most active during the hottest hours of the day. On warm days, M. nuda females will guard the entrances to their nests, preventing the cuckoo bees mode of parasitism.[12]

References

- Mitchell, T.B. (1960). "Bees of the Eastern United States". North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin (141).

- Cane, James H. (October 1983). "Foraging, grooming and mate-seeking behaviors of Macropis nuda (Hymenoptera, Melittidae) and use of Lysimachia ciliata (Primulaceae) oils in larval provisions and cell linings". American Midland Naturalist. 110 (2): 257–264. doi:10.2307/2425267. JSTOR 2425267.

- Michez, Denis; Patiny, Sébastien (2005-01-01). "World revision of the oil-collecting bee genus Macropis Panzer 1809 (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Melittidae) with a description of a new species from Laos". Annales de la Société Entomologique de France. New Series. 41 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1080/00379271.2005.10697439. ISSN 0037-9271.

- Rozen, Jerome; Jacobson, Ned Robert (September 22, 1980). "Biology and immature stages of Macropis nuda, including comparisons to related bees (Apoidea, Melittidae)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 2702: 1–11.

- Cane, James H. (1991). "Soils of Ground-Nesting Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea): Texture, Moisture, Cell Depth and Climate". Journal of the Kansas Entomology Society (64(4), 1991, pp. 406–413).

- Stephen, W.P. (1969). "The Biology and External Morphology of Bees with a Synopsis of the Genera of Northwestern America". Agricultural Experiment Station.

- Schäffler, Irmgard; Dötterl, Stefan (2011-05-25). "A day in the life of an oil bee: phenology, nesting, and foraging behavior" (PDF). Apidologie. 42 (3): 409–424. doi:10.1007/s13592-011-0010-3. ISSN 0044-8435.

- Schäffler; Dötterl (February 2007). "Flower scent of floral oil-producing Lysimachia punctata as attractant for the oil-bee Macropis fulvipes". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 33 (2): 441–445. doi:10.1007/s10886-006-9237-2. PMID 17151908.

- Schäffler, Irmgard; Steiner, Kim E.; Haid, Mark; Berkel, Sander S. van; Gerlach, Günter; Johnson, Steven D.; Wessjohann, Ludger; Dötterl, Stefan (2015-08-06). "Diacetin, a reliable cue and private communication channel in a specialized pollination system". Scientific Reports. 5: 12779. doi:10.1038/srep12779. PMC 4526864. PMID 26245141.

- Pekkarinen, A.; Berg, Ø.; Calabuig, I.; Janzon, L.-Å.; Luig, J. (2003). "Distribution and co-existence of the Macropis species and their cleptoparasite Epeoloides coecutiens (Fabr.) in NW Europe Hymenoptera: Apoidea, Melittidae and Apidae)" (PDF). Entomologica Fennica. 14 (1): 53–59.

- Rozen, J. G. Jr. (1977). "Biology and Immature stages of the bee genus Meganomia (Hymenoptera, Melittidae)". American Museum Novitates (2630, pp. 1–14, 27 fig).

- Straka, J.; Bogusch (2007). "Description of immature stages of cleptoparasitic bees Epeoloides coecutiens and Leiopodus trochantericus (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Osirini, Protepeolini) with remarks to their unusual biology". Entomologica Fennica. 18: 242–254.