Macaulay's method

Macaulay’s method (the double integration method) is a technique used in structural analysis to determine the deflection of Euler-Bernoulli beams. Use of Macaulay’s technique is very convenient for cases of discontinuous and/or discrete loading. Typically partial uniformly distributed loads (u.d.l.) and uniformly varying loads (u.v.l.) over the span and a number of concentrated loads are conveniently handled using this technique.

The first English language description of the method was by Macaulay.[1] The actual approach appears to have been developed by Clebsch in 1862.[2] Macaulay's method has been generalized for Euler-Bernoulli beams with axial compression,[3] to Timoshenko beams,[4] to elastic foundations,[5] and to problems in which the bending and shear stiffness changes discontinuously in a beam.[6]

Method

The starting point is the relation from Euler-Bernoulli beam theory

Where is the deflection and is the bending moment. This equation[7] is simpler than the fourth-order beam equation and can be integrated twice to find if the value of as a function of is known. For general loadings, can be expressed in the form

where the quantities represent the bending moments due to point loads and the quantity is a Macaulay bracket defined as

Ordinarily, when integrating we get

However, when integrating expressions containing Macaulay brackets, we have

with the difference between the two expressions being contained in the constant . Using these integration rules makes the calculation of the deflection of Euler-Bernoulli beams simple in situations where there are multiple point loads and point moments. The Macaulay method predates more sophisticated concepts such as Dirac delta functions and step functions but achieves the same outcomes for beam problems.

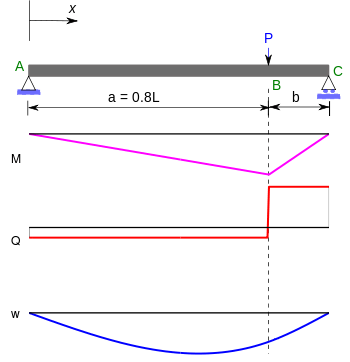

Example: Simply supported beam with point load

An illustration of the Macaulay method considers a simply supported beam with a single eccentric concentrated load as shown in the adjacent figure. The first step is to find . The reactions at the supports A and C are determined from the balance of forces and moments as

Therefore, and the bending moment at a point D between A and B () is given by

Using the moment-curvature relation and the Euler-Bernoulli expression for the bending moment, we have

Integrating the above equation we get, for ,

At

For a point D in the region BC (), the bending moment is

In Macaulay's approach we use the Macaulay bracket form of the above expression to represent the fact that a point load has been applied at location B, i.e.,

Therefore, the Euler-Bernoulli beam equation for this region has the form

Integrating the above equation, we get for

At

Comparing equations (iii) & (vii) and (iv) & (viii) we notice that due to continuity at point B, and . The above observation implies that for the two regions considered, though the equation for bending moment and hence for the curvature are different, the constants of integration got during successive integration of the equation for curvature for the two regions are the same.

The above argument holds true for any number/type of discontinuities in the equations for curvature, provided that in each case the equation retains the term for the subsequent region in the form etc. It should be remembered that for any x, giving the quantities within the brackets, as in the above case, -ve should be neglected, and the calculations should be made considering only the quantities which give +ve sign for the terms within the brackets.

Reverting to the problem, we have

It is obvious that the first term only is to be considered for and both the terms for and the solution is

Note that the constants are placed immediately after the first term to indicate that they go with the first term when and with both the terms when . The Macaulay brackets help as a reminder that the quantity on the right is zero when considering points with .

Boundary Conditions

As at , . Also, as at ,

or,

Hence,

Maximum deflection

For to be maximum, . Assuming that this happens for we have

or

Clearly cannot be a solution. Therefore, the maximum deflection is given by

or,

Deflection at load application point

At , i.e., at point B, the deflection is

or

Deflection at midpoint

It is instructive to examine the ratio of . At

Therefore,

where and for . Even when the load is as near as 0.05L from the support, the error in estimating the deflection is only 2.6%. Hence in most of the cases the estimation of maximum deflection may be made fairly accurately with reasonable margin of error by working out deflection at the centre.

Special case of symmetrically applied load

When , for to be maximum

and the maximum deflection is

References

- W. H. Macaulay, "A note on the deflection of beams", Messenger of Mathematics, 48 (1919), 129.

- J. T. Weissenburger, ‘Integration of discontinuous expressions arising in beam theory’, AIAA Journal, 2(1) (1964), 106–108.

- W. H. Wittrick, "A generalization of Macaulay’s method with applications in structural mechanics", AIAA Journal, 3(2) (1965), 326–330.

- A. Yavari, S. Sarkani and J. N. Reddy, ‘On nonuniform Euler–Bernoulli and Timoshenko beams with jump discontinuities: application of distribution theory’, International Journal of Solids and Structures, 38(46–7) (2001), 8389–8406.

- A. Yavari, S. Sarkani and J. N. Reddy, ‘Generalised solutions of beams with jump discontinuities on elastic foundations’, Archive of Applied Mechanics, 71(9) (2001), 625–639.

- Stephen, N. G., (2002), "Macaulay's method for a Timoshenko beam", Int. J. Mech. Engg. Education, 35(4), pp. 286-292.

- The sign on the left hand side of the equation depends on the convention that is used. For the rest of this article we will assume that the sign convention is such that a positive sign is appropriate.

See also

- Beam theory

- Bending

- Bending moment

- Singularity function

- Shear and moment diagram

- Timoshenko beam theory