Lydia Welti-Escher

Lydia Welti Escher, (née Lydia Escher, 10 July 1858 in Zürich-Enge – 12 December 1891 in Genève-Champel) was a Swiss patron of the arts and the daughter of Augusta Escher-Uebel (1838–1864) and Alfred Escher (1819–1882), among others the founder of the Gotthardbahn. Lydia Escher was one of the richest women of Switzerland in the 19th century, patron of the arts and established the Gottfried Keller Foundation.

Lydia Welti-Escher | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Lydia Escher-Welti by Karl Stauffer-Bern, Kunsthaus Zürich | |

| Born | Lydia Escher 10 July 1858 |

| Died | 12 December 1891 (aged 33) |

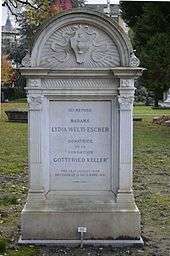

| Monuments | Gottfried Keller Stiftung Plaque by the Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster at the Kunsthaus Zürich museum Lydia Welti-Escher Hof square in Zürich |

| Nationality | Switzerland |

| Other names | Lydia Escher |

| Years active | 1874–1891 |

| Known for | Swiss Maecenas |

Notable work | Gottfried Keller Foundation |

| Spouse(s) | Friedrich Emil Welti |

| Partner(s) | Karl Stauffer-Bern |

Life

Origins and family

Lydia Escher was born into the Escher vom Glas family, an old and influential Zürich family dynasty, as daughter of Augusta Escher-Uebel (1838–1864) and Alfred Escher (1819–1882). A scandal surrounding Alfred Escher's immediate forebears had, however, damaged her family line's reputation. Hans Caspar Escher-Werdmüller (1731–1781) had fathered a child out of wedlock with a maidservant in 1765 and emigrated. His son Hans Caspar Escher-Keller (1755–1831) almost brought Zürich to financial ruin when he went bankrupt. Finally Alfred Escher's father Heinrich Escher (1776–1853) made a new fortune through speculative land deals and trading in Northern America. In 1814 Heinrich returned to Zürich and married Lydia Zollikofer (1797–1868) in May 1815, having two children, Clementine (1816–1886) and Alfred. In 1857 Alfred Escher married Augusta Escher-Uebel (1838–1864): Lydia was born in 1858, but her sister Hedwig (1861–1862) died while still a baby. Lydia's suicide on 12 December 1891 brought the end to Alfred Escher's family line.[1]

Childhood and youth

Lydia Escher's grandfather Heinrich Escher had built the country house Belvoir on the left shore of Zürichsee in the then village of Enge, as of today a district of the city of Zürich, where Lydia grew up and lived. Heinrich Escher was able to devote himself fully to his passion for botany and his entomological collection, that also was cared by her father, and by Lydia. At the age of four years, Lydia lost her younger sister, and Lydia's mother died in 1864. So Alfred Escher was able to see his daughter several times a day, he rented for Lydia and her governess an apartment near his workplace in the city of Zürich. Since he is no longer married, Lydia is increasingly becoming also a close friend and started to support his work actively. Alfred Escher tried as often as possible to spend time with his daughter, and they maintained a cordial relationship.[2]

Lydia Escher's youth differed substantially from those of other young women of Zürich from bourgeois origin: Lydia conducted her father's correspondence, ran the household in the Belvoir estate, and she grew into the role of the hostess and entertainer of the numerous guests of Alfred Escher, among them the Swiss poet Gottfried Keller which was also a fatherly friend. Lydia Escher was a self-confident young woman, who read extensively, mastered several languages and gladly attended music and theatre performances. In her letters to her childhood friend, the painter Louise Breslau, she told to take singing and piano lessons, and Lydia was inspired by her creative genius.[3]

In addition to personal attacks from political opponents, Lydia's father faced serious health problems. He suffered repeated bouts of ill health throughout his life and on many occasions was obliged to spend long periods in convalescence. During the critical phase of the Gotthard Rail Tunnel construction in the mid-1870s, Escher nearly worked himself to death. In 1878 he fell so badly ill that he was unable to leave Belvoir for weeks. His life became a constant alternation between illness and recovery. However, fulfilling his political and business obligations, in late November 1882 Alfred Escher fell badly ill again, and in the morning of 6 December 1882 Alfred Escher died on his Belvoir estate. Throughout, Escher has been lovingly cared of his daughter, and she was regarded to be his only confidante, who oversaw much of his correspondence and accompanied her father on his many travels.

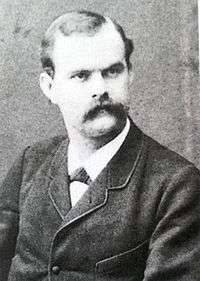

Marriage with Friedrich Emil Welti

Because the relationship between Alfred Escher and his former protege Emil Welti had deteriorated before, Escher was against Lydia's engagement with Welti's son Friedrich Emil. Since the engagement was already published, Lydia married after her father's death on 4 January 1883. Friedrich Emil Welti was the son of the Swiss Federal Councillor (Bundesrat) Emil Welti, one of the then most powerful people in Switzerland, and former companion and later opponent of Lydia's father. Welti rose in the Swiss economic circles thanks to his marriage with Lydia and sat on numerous board of directors. Meanwhile, Lydia Welti-Escher bored rapidly, not fulfilled by the management of Welti's comparatively modest household, and was missing interesting guests and stimulating conversations as she had in her father's household. Through her husband, she finally came in contact with his childhood friend Karl Stauffer-Bern, a known Swiss painter, in August 1885, and henceforth Stauffer was on occasion of his travels to Zürich a guest at the Belvoir mansion. In his own atelier in the spacious park area, Stauffer portrayed Lydia Escher, but also Lydia's fatherly friend Gottfried Keller. Lydia and Emil Welti-Escher enabled Stauffer to work in Rome. In October 1889 Lydia and her husband moved to Florence, but shortly after, Friedrich Emil Welti went for financial reasons back to Switzerland, and left his wife in care of Karl Stauffer.[2][4]

Liaison with Karl Stauffer-Bern

Lydia and Stauffer fell in love, and Lydia told to Stauffer's mother to marry him. In 1888, still under the sponsorship of his patrons, the Welti-Escher family, Karl Stauffer-Bern went to Rome to study sculpture. While there, the liaison of Lydia Welti-Escher with him got in the public focus,[5] the Welti family was outraged, and Lydia and Karl escaped to Rome.[2] Even the divorce from her husband was proposed, but Welti contacted the Swiss Embassy in Rome and used his considerable influence to separate them. Lydia was placed in a public insane asylum in Rome, and Stauffer-Bern was jailed after being charged with even kidnapping and rape.[6] While staying there, Lydia posted the feminist (emancipatory) publication Gedanken einer Frau (literally: Thoughts of a woman) and planned to publish it. The document is still disappeared,[2] as well as the majority of Lydia Escher's comprehensive correspondency was probably destroyed during this time. It is significant that still an important part of the Welti family archives is not accessible to researchers and historians.[2]

In May 1890, a full psychiatric report showed no sign of mental illness and Lydia Welti-Escher was released, she returned to her husband, although she soon filed for a divorce, which was eventually granted. In a state of despondency over the loss of his love, Karl Stauffer-Bern suffered a nervous breakdown, spent some time in the San Bonifazio mental hospital, and after his release, he attempted suicide by gun.[5] In January 1891, unable to work and apparently suffering from persecution mania, he committed suicide.[6]

Stigmatization and suicide

After four months of internment in the public psychiatric hospital in Rome,[3] Lydia Escher was finally brought back by her husband to Switzerland. She approved his desire of divorce and a financial agreement, which committed Lydia to a payment of 1.2 million Swiss Francs 'compensation' to Welti. In the 'high society' of Zürich, Lydia was no longer accepted, and she was ostracized as an adulteress. Therefore, she moved into a house in Genève-Champel in the late summer of 1890. There Lydia Escher finished her last goal in life, the establishment of an Arts foundation, later named Gottfried Keller Stiftung, which she devoted to her fatherly friend from her youth. Lydia Welti-Escher decided to end her life on 12 December 1891; she opened the gas tap in her villa near Geneva.[2]

It was controversial discussed, whether according to Josef Jung's biography, Lydia had been examined after her detention in the psychiatric clinic in Rome, and upon returning to Switzerland (again) in the clinic of Königsfelden, if she resided there. The biographer Willi Wottreng claimed, for a further stay in Königsfelden, there are no sources; This is important, because it shows that Lydia Welti-Escher had resisted the will of her husband and father-in-law, thus demonstrating to be an emancipated woman after the events in Italy. The recently published psychiatric report about Lydia Escher, dated 27 May 1890, showed that her internment in the clinicum in Roma and the diagnosis of systematic madness was fictitious.[7] Also from today's perspective, the argument way of the reviewers and their conclusion, that Lydia Escher was in possession of their full mental health, convinced.[8][9]

Selected portraits

Lydia's Mother Augusta Escher (around 1850)

Lydia's Mother Augusta Escher (around 1850) Lydia Welti-Escher, portrait by Karl Stauffer-Bern (date unknown)

Lydia Welti-Escher, portrait by Karl Stauffer-Bern (date unknown) Friedrich Emil Welti, photograph (artist and date unknown)

Friedrich Emil Welti, photograph (artist and date unknown) Karl Stauffer-Bern, self-portrait (date unknown)

Karl Stauffer-Bern, self-portrait (date unknown) Gottfried Keller, portrait by Karl Stauffer (1886)

Gottfried Keller, portrait by Karl Stauffer (1886)

Gottfried Keller Foundation

In 1890, shortly before the end of her tragic life, Lydia Escher invested the Escher family's fortune in a foundation, which she called the Gottfried Keller-Stiftung (GKS), named after Gottfried Keller to whom her father gave consistent support. With her remaining substantial asset – Villa Belvoir and marketable securities totaling nominally 4 million Swiss Francs – Lydia Escher established the foundation's base. According to the will of Lydia Escher, the foundation was established on 6 June 1890, and was managed by the Swiss Federal Council, thus, Lydia Escher wished to accomplish a patriotic work. The foundation should also promote the independent work of women, at least in the field of the applied of Arts, according to the original intention of the founder. This purpose was adopted – but at the urging of Welti not in the deed of the foundation. The Gottfried Keller Foundation became though an important collection institution for art, but the feminist concerns of Lydia Escher but was not met.[2]

Aftermath and monuments

The Gottfried Keller foundation, as of today is based in Winterthur, and it is listed as a Swiss inventory of cultural property of national and regional significance.[10]

Lydia Escher is considered an outstanding woman of the Belle Époque in Switzerland, she blew up close social and moral standards of existence by their liaison with an artist, to which she open stood; and, on the other hand, Lydia Escher's historic achievement is in the creation of a Swiss art foundation of national importance. Lydia Escher, as a prominent patron of the arts, was honored by the Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster association on the occasion of her 150th anniversary by a commemorative plaque, located at a spot in front of the Kunsthaus Zürich.[2]

The place was baptized on 20 August 2008 by the city of Zürich as Lydia Welti-Escher Hof.[11][12][13][14]

In television and theater

- 2014: Die letzten Stunden der Lydia Welti-Escher. Play after Christine Ahlborn.[15]

- 2013: Die Schweizer: Kampf um den Gotthard – Alfred Escher und Stefano Franscini. Television documentary play produced by Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (SRF)[16]

Literature

- Willi Wottreng: Lydia Welti-Escher. Eine Frau in der Belle Epoque. Elster-Verlag, Zürich 2014, ISBN 978-3-906065-22-9.

- Joseph Jung: Lydia Welti-Escher (1858–1891). Mit einer Einführung von Hildegard Elisabeth Keller. NZZ Libro, Zürich 2013, ISBN 978-3-03823-852-2.

- Joseph Jung: Lydia Welti-Escher (1858–1891). Biographie. Quellen, Materialien und Beiträge. NZZ Libro, Zürich 2009, ISBN 978-3-03823-557-6.

- Willi Wottreng: Die Millionärin und der Maler: Die Tragödie Lydia Welti-Escher und Karl Stauffer-Bern. Orell Füssli, Zürich 2008, ISBN 978-3-280-06049-0.

- Hanspeter Landolt: Gottfried Keller-Stiftung. Sammeln für die Schweizer Museen. 1890–1990. 100 Jahre Gottfried Keller-Stiftung. Benteli, Bern 1990, ISBN 978-3716506967.

- Bernhard von Arx: Der Fall Stauffer. Chronik eines Skandals. Hallwag, Bern 1969, ISBN 3-7296-0408-2.

- Lukas Hartmann: Ein Bild von Lydia. Diogenes, Zürich 2018, ISBN 978-3-257-07012-5.[17]

References

- Jung: Alfred Escher. 2009, pp. 464–492; Jung: Lydia Welti-Escher, 2009.

- "Ehrung der Kunstmäzenin Lydia Welti-Escher (press release)" (PDF) (in German). Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster. 27 March 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Anna Katharina Bähler (11 October 2013). "Welti [-Escher], Lydia". HDS. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Luzius Winkler (October 2004). "Der Belvoirpark" (in German). HEV 10/2004. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Karl Stauffer-Bern". spartacus-educational.com. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Paul Schlenther (1893). "Stauffer, Karl" (in German). ADB. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Jung: Lydia Welti-Escher. 2009, p. 146 (Psychiatrisches Gutachten); Wottreng: Die Millionärin und der Maler, p. 146; Von Arx: Der Fall Stauffer, p. 269.

- Daniel Hell: Das Gutachten aus heutiger Sicht, in: Jung: Lydia Welti-Escher. 2009, p. 359.

- Jung: Lydia Welti-Escher. 2009, p. 163; von Arx: Der Fall Stauffer, p. 275.

- "A-Objekte KGS-Inventar". Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, Amt für Bevölkerungsschutz. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Stadtrat von Zürich (20 August 2008). "Strassenbenennungskommission; Benennung von "Lydia-Welti-Escher-Hof" (press release)" (in German). Stadt Zürich. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "Der Lydia-Welti-Escher-Hof" (in German). Gang dur Alt-Züri. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "Frauenehrungen" (in German). Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Frauenehrungen der Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster" (PDF) (in German). Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- "Eine Frau erstickt an den Zwängen ihrer Umwelt" (in German). Badische Zeitung. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "Die Schweizer: Kampf um den Gotthard – Alfred Escher und Stefano Franscini" (in German). Swiss television SRF. 28 November 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "Lukas Hartmann Bücher" (in German). Ex Libris (bookshop). Retrieved 6 April 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lydia Welti-Escher. |

- Anna Katharina Bähler: Welti [-Escher], Lydia in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 11 October 2013.

- Literature by and about Lydia Welti-Escher in the German National Library catalogue

- Gottfried Keller Stiftung, Bundesamt für Kultur (in German)

- Lydia Welti-Escher on the website of the Swiss Archives (Bundesarchiv) (in German)

- Lydia Welti-Escher in the German National Library catalogue

- Digital edition of Alfred Escher's correspondence (in German)

- Lydia Escher on the website of the Swiss television SRF (in German)