Lunary

A lunary (from Latin lunarium), also called a selenodromion or moonbook, is a book of prognostication based on the position of the moon at any given time.[1][2] It is an astrological genre with parallels as far back as Akkadian literature. From the 2nd century AD, it is common in the Greco-Roman world.[3] There are examples in Greek, Latin, Coptic, Middle English and Old Nubian.[3][4] Pagan, Jewish and Christian examples are known.[3] The lunary was "by far the most popular and widely circulated prognostic genre" during the Middle Ages.[5] Byzantine.[6]

Use of the term "lunary" for the genre is a modern convention. In Middle English, lunarie referred to volvelles and not prognostic texts. The Latin lunaria had a similar usage.[1] The term "lunary" is sometimes applied to the practice of creating lunaries and determining propitious days on the basis of the moon, a form of hemerology.[6]

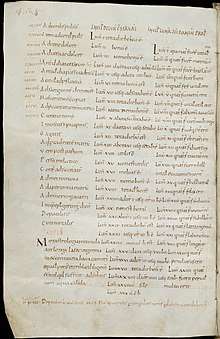

Lunaries are similar to electionaries in that they were used for choosing (electing) astrological propitious dates for events. They differ in that they limit themselves to the moon, ignoring the other planets and stars.[1] Lunaries were used for predicting and planning birth, business, death, illness, marriage, planting, phlebotomy and travel. There are two main types of lunary: the day or mansion lunary, which is concerned with the station of the moon in its cycle (lunar month of 28 days or synodic month of 30), and the month or sign lunary, which is concerned with the moon's successive risings in the twelve signs of the Zodiac.[7] There are picture lunaries in which the things to be done or avoided on a given day of the moon are illustrated.[8]

Notes

- Means 1992, p. 376.

- Chardonnens 2017, p. 375.

- Torijano 2013, p. 299 [270].

- Łajtar & Van Gerven Oei 2020, abstract.

- Means 1992, p. 378.

- Chardonnens 2017, p. 379.

- Means 1992, pp. 378–379.

- Chardonnens 2017, p. 381.

Bibliography

- Chardonnens, László Sándor (2007). Anglo-Saxon Prognostics, 900-1100: Study and Texts. Brill.

- Chardonnens, László Sándor (2017). "Hemerology in Medieval Europe". In Donald Harper; Marc Kalinowski (eds.). Books of Fate and Popular Culture in Early China: The Daybook Manuscripts of the Warring States, Qin, and Han. Brill. pp. 373–407.

- Łajtar, Adam; Van Gerven Oei, Vincent W. J. (2020). "An Old Nubian Lunary with a Greek Addition from Gebel Adda". Le Muséon. 133 (1–2): 13–30. doi:10.2143/MUS.133.1.3287659.

- Means, Laurel (1992). "Electionary, Lunary, Destinary, and Questionary: Toward Defining Categories of Middle English Prognostic Material". Studies in Philology. 89 (4): 367–403. JSTOR 4174433.

- Taavitsainen, Irma (1988). Middle English Lunaries: A Study of the Genre. Société Néophilologique.

- Torijano, Pablo A. (2013). "The Selenodromion of David and Solomon" (PDF). In Richard Bauckham; James Davila; Alex Panayotov (eds.). Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures. Vol. 1. pp. 298–304.