Lucius Caecilius Iucundus

Lucius Caecilius Iucundus (born c. 14 A.D., fl. 62 A.D.) was a banker who lived in the Roman town of Pompeii around 14 A.D.–62 A.D. His house still stands and can be seen in the ruins of the city of Pompeii which remain after being partially destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. This house is known for its beauty, along with some material found about bank book-keeping and wax tablets, which were receipts. He is well known for being a central character in the Cambridge Latin Course series.

Lucius Caecilius Iucundus | |

|---|---|

%2C_Pompeii%2C_c._79_AD%2C_National_Archaeological_Museum%2C_Naples_-_Spurlock_Museum%2C_UIUC_-_DSC05672_(cropped).jpg) | |

| Born | 14 AD |

| Died | 62 (aged 47–48) (assumed, actual death date unknown) |

| Known for | Pompeian banker |

| Spouse(s) | Metella |

| Children | Lucia (daughter) |

Life

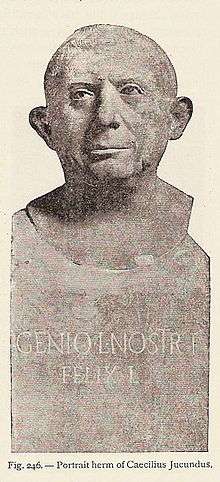

The Pompeian banker Caecilius was born around the end of Augustus's reign (c. 14 AD) to a freedman named Felix, who was also a banker.[1] By 58 AD he was well-established as a successful banker who dealt with a wide variety of Pompeians.[2] Freedmen and slaves performed many small business tasks for Iucundus, such as signing receipts as witnesses and collecting payments from clients. Many names of elite Pompeian citizens occur frequently in his transaction records, suggesting that Caecilius also had dealings with the upper class of his town. In fact, he even traveled to nearby Nuceria to help the wealthy Praetorian Guard senior centurion Publius Alfenus Varus resell some slaves that he had purchased in an auction.[3]

He had at least two sons, Sextus Caecilius Iucundus Metellus (after his wife) and Quintus Caecilius Iucundus. Caecilius departed from the traditional naming system, giving each of his sons a name that implied a relationship with the illustrious family of the Caecilii Metelli.[4]

The tablets that Caecilius left behind suggest that he died in the earthquake on 5 February 62, since his records stop a few days before that date.[5]

Banking in Pompeii

Caecilius was a type of banker called an argentarius, which meant that he acted as a middleman in auctions. The Pompeian argentarius would pay the vendor for the purchased item and then grant the buyer a time frame in which to repay him. According to the records of Caecilius, mostly dating from the 50s, the buyers had between a few months and a year to repay the loan to the argentarius.[6]

The argentarius would receive interest on the loan, as well as a commission known as a merces.[7] Some argentarii, called coactores argentarii, collected debt money in addition to making arrangements in the auctions, while other argentarii were assisted by coactores who collected the debts for them. It is uncertain whether Caecilius was a coactor argentarius or simply an argentarius.

Wax tablets

Caecilius kept many private records of his business transactions on wax tablets, many of which were found in his house in 1875.[8] Of the 153 tablets discovered, sixteen document contracts between Caecilius and the city of Pompeii; the remaining 137 are receipts from auctions on behalf of third parties.[9] Seventeen of these tablets record loans that he advanced to buyers of auction items.[10]

In addition to the transaction information, Caecilius' tablets record the names of vendors and witnesses to the arrangements. The lists of witnesses also give some insight into the social structure of Pompeii, since Caecilius had his witnesses sign in order of social status.[11]

The tablets themselves are triptychs, which means that they have three wooden leaves tied together to make six pages.[12] Wax was put on the inner four pages, and the receipt was written on these surfaces. The tablet was then closed and wrapped with a string, over which the witnesses placed their wax seals. This prevented the document itself from being altered, and there was a brief description of the receipt written on the outside for identification purposes.[13]

Inscription from a tablet

The following is the translation of a 56 AD receipt for the proceeds of an auction sale.

Umbricia Ianuaria declared that she had received from L. Caecilius Iucundus 11,039 sesterces, which sum came into the hands of L. Caecilius Iucundus by agreement as the proceeds of an auction sale for Umbricia Ianuaria, the commission due him having been deducted.

Done at Pompeii on the twelfth day of December, in the consulship of Lucius Duvius and Publius Clodius.

Seal of Quintus Appuleius Severus, Marcus Lucretius Lerus, Tiberius Julius Abascantius, M. Julius Crescens, M. Terentius Primus, M. Epidius Hymenaeus, Q. Granius Lesbus, Titus Vesonius Le…., D. Volcius Thallus.[14]

In this inscription, Caecilius was very exact in the details. He included the date and the list of witnesses, which were listed in descending order of social status. So by examining several of his tablets, it is possible to determine the relative social standings of clients with whom Caecilius arranged numerous transactions.

House

Part of Caecilius' house still stands on Stabiae Street in Pompeii today,[15] and it provides many interesting pieces of information both about Caecilius and Pompeii. Archaeologists discovered the wax tablets there, and the Lararium, or shrine, in his house features a relief depicting the Temple of Jupiter during the 62 AD earthquake.[16] The atrium was once decorated with paintings. The floor is decorated with a black and white mosaic and at the entrance a reclining dog is depicted.

Several graffiti messages have been found on the walls of the house, including one that reads "May those who love prosper; let them perish who cannot love; let them perish twice over who veto love."[17] The tablinum, or study, in Caecilius' house contains some beautiful wall paintings, and an amphora given by one of his sons to the other was also found in the house.[4]

Depictions in fiction

Book One of the Cambridge Latin Course is a fictional account of the life of Iucundus, who is referred to as Caecilius in the series.[18] In the book he has a wife, Metella, whose name means "little basket of stones", and a son, Quintus, on whom books two and three in the series are based. He also has two slaves; a gardener named Clemens, and a cook named Grumio. It is also revealed that Caecilius once had another slave, Felix. However, after he saved Quintus from a kidnapping attempt, the banker released him. In the book, Caecilius dies in the 79 AD eruption of Vesuvius. However, as stated earlier, it is now believed that he actually perished in the 62 AD earthquake that preceded the eruption, since the records of his negotiated contracts cease shortly before then.

Caecilius, along with his banking profession, also has a minor role in Robert Harris's 2003 novel Pompeii.

In a 2008 episode of television science-fiction series Doctor Who entitled "The Fires of Pompeii", Peter Capaldi portrays Lobus Caecilius, a marble merchant based on Caecilius. In this story, he and his family are saved from the eruption by the Doctor, who transports them to safety.[19]

References

- Alex Butterworth and Ray Laurence, Pompeii: The Living City (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), 75.

- Butterworth and Laurence, Pompeii: The Living City, 75

- Butterworth and Laurence, Pompeii: The Living City, 77.

- August Mau, Pompeii: Its Life and Art, trans. Francis W. Kelsey (New York: The Macmillan Company, 2nd ed. 1902), p.507.

- Butterworth and Laurence, Pompeii: The Living City, 159.

- The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed. (London: Cambridge University Press, 1970), 772.

- The Cambridge Ancient History, 773.

- Jean Andreau, Banking and Business in the Roman World, trans. Janet Lloyd (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 71.

- The Cambridge Ancient History, 884.

- Andreau, Banking and Business in the Roman World, 44.

- The Cambridge Ancient History, 885.

- Mau, Pompeii: Its Life and Art, p.499.

- Mau, Pompeii: Its Life and Art, p.500. To read about the tablets in greater detail and to view pictures of reconstructed tablets, see pp. 499-501. On-line version only has text, not images.

- To view the original Latin inscription and English translation together, see Mau, Pompeii: Its Life and Art, pp. 502-3.

- Mau, Pompeii: Its Life and Art, p.352.

- Paul Zanker, Pompeii: Public and Private Life, trans. Deborah Lucas Schneider (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 106.

- Butterworth and Laurence, Pompeii: The Living City, 134.

- http://www.cambridgescp.com/Upage.php?p=clc%5Eoa_book1%5Estage1

- "Overseas filming for ambitious episode". BBC. 25 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lucius Caecilius Iucundus. |