Lucas Malet

Lucas Malet was the pseudonym of Mary St Leger Kingsley (4 June 1852 — 27 October 1931), a Victorian novelist. Of her novels, The Wages of Sin (1891) and The History of Sir Richard Calmady (1901) were especially popular.[1] Malet scholar Talia Schaffer notes that she was "widely regarded as one of the premier writers of fiction in the English-speaking world"[2] at the height of her career, but her reputation declined by the end of her life and today she is rarely read or studied. At the height of her popularity she was "compared favorably to Thomas Hardy, and Henry James, with sales rivaling Rudyard Kipling."[2] Malet's fin de siecle novels offer "detailed, sensitive investigations of the psychology of masochism, perverse desires, unconventional gender roles, and the body."[2]

.png)

Early years

She was born at the rectory in Eversley, Hampshire, the younger daughter of Reverend Charles Kingsley (author of The Water Babies) and his wife Frances Eliza Grenfell, the third of the couple's four children.[3] Her paternal uncles Henry Kingsley and George Kingsley were both writer and her cousin Mary Kingsley was an African traveller and ethnologist. Kingsley was educated at home and studied art with Sir Edward Poynter.[4] She was for a time a student at the Slade School.[3]

Career

In 1876, she married the Rev. William Harrison,[5] a colleague of her father's, Minor Canon of Westminster, and Priest-in-Ordinary to the Queen. Malet gave up artistic aspirations after the marriage.[4] The marriage was childless and unhappy, and the couple soon separated. After the separation, Malet embarked on an independent writing career, forming her pen name by combining two little-known family names. Her first novel, Mrs. Lorimer, a Sketch in Black and White, was published in 1882.[6] Critical attention and praise came with Malet's second novel, Colonel Enderby's Wife, published in 1885, which fictionalized her brief failed marriage. Five years after her husband's death, Kingsley became a convert to Catholicism.[3]

Malet lived for most of her life on the Continent with the singer Gabrielle Vallings.[7] Vallings, much younger than Malet, was the author's cousin, romantic companion and adopted daughter. The two traveled abroad frequently together, including spending significant time in France. Malet spent much of the end of her life in France where she was a part of "high literary circles."[4] She wrote frequently during this time, often out of economic necessity. Despite her tremendous critical and economic success during the height of her career, Malet died in penury at the home of a friend in Wales on 27 October 1931.[4][3]

Literary development

Despite a lack of attention to Malet,[2] it is known that Malet wrote at least 17 novels, two books of short fiction, many short stores, literary essays, and poems.[4] She also finished at least one of her father's novels.[4] Talia Schaffer notes that her "literary ideologies were shaped by writers ranging from George Eliot to Zola."[2] Her father, niece and cousin were all writers as well, but today Malet remains the least studied of the Kingsley writers:[4] her "authorial persona emerges as a way to escape her biographical situation."[2] Malet's first novel was Mrs. Lorimer, a Sketch in Black and White, (1882) while her first critical success was Colonel Enderby's Wife (1885). The Wages of Sin, generally regarded as one of Malet's most important novels, was published in 1891: the novel is believed by some critics to have been a major influence on Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure.[4] The late nineteenth century English author George Gissing thought it 'a wooden book, without a living character or touching scene. The dialogue preposterous. So much for popular success'. On the other hand he described her 1888 novel A Counsel of Perfection as 'not bad'.[8] Henry James was both an admirer of Malet's writing and eventually a close personal friend.[4] Malet's The Gateless Barrier (1900) is a novel-length ghost story[9] – an example of how, where her early novels were genteel Victorian romances, by the 1890s Malet was using the ideas of the aesthetic movement to explore more transgressive themes, such as adultery and sadism.[10]

Her later novels, such as The Survivors (1923) are proto-modernist in their explorations of marginal consciousnesses.[10] E. F. Benson acknowledged his debt to her critical advice in his memoir Our Family Affairs.[11] Despite her importance, Malet died in poverty in 1931. Her last novel, The Private Life of Mr. Justice Syme, was completed after the author's death by her companion Gabrielle Vallings, and published in August 1932.[6] Biographer Patricia Lorimer Lundberg attributes Malet's swift decline in reputation to multiple factors including the author's confusing sexual and gender politics and an "evolving modernist style" that "met with sloppy reviews that endeavored to push her back into Victorianism."[12] Lundberg's book, An Inward Necessity: the Writer's Life of Lucas Malet, remains the only major biography of the author. Talia Schaffer notes that Lundberg's book re-constructs historical gaps in the author's life created both by critical neglect and Malet's own actions (she asked Vallings to burn her personal papers, for example.)[2] The biography uses Malet's life and work to show "how late Victorian conditions fostered an oeuvre as ambitious as Malet's and how the advent of modernism damaged her reputation."[2]

Selected works

Novels

- Mrs Lorimer: A Study in Black and White (1882)

- Colonel Enderby's Wife (1885)

- Little Peter: A Christmas Morality for Children of Any Age (1888)

- A Counsel of Perfection (1888)

- The Wages of Sin (1891)

- The Carissima: A Modern Grotesque (1896)

- The Gateless Barrier (1900)

- The History of Sir Richard Calmady (1901), based on the life of Arthur MacMorrough Kavanagh

- The Far Horizon (1906)

- The Wreck of the Golden Galleon (1910)

- Adrian Savage (1911)

- Damaris (1916)

- Deadham Hard (1919)

- The Tall Villa (1920)

- The Survivors (1923)

- The Dogs of Want: A Modern Comedy of Errors (1924)

She also completed her father's unfinished novel The Tutor's Story.

Short stories and novellas

- Little Peter: A Christmas Morality for Children of any Age (1887)

- The Score (1909)

- Da Silva's Widow and Other Stories (1922)

- "A Conversion" (Published in World Fiction 1922. It was later republished as "The Pool" in London Magazine 1930)

- "The Lay Figure" (Published in The Graphic 1923)

Example of one of her books

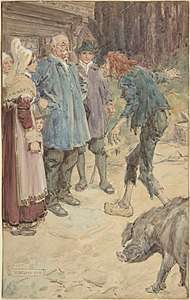

In 1887, Kegan Paul & Co.[note 1] published Kingsley's short[note 2] book Little Peter: A Christmas Morality for Children of any Age with nine full page illustrations including the frontpiece, and several smaller ones, by Paul Hardy.[note 3] The book tells the story of a small boy who befriends a very ugly and socially-despised man, who saves him in the end. The story was apparently popular as it was reprinted numerous times, most recently in 2010. In 1909, Henry Frowde and Hodder & Stoughton's joint venture reissued the book, but this time with eight full-page colour illustrations, including the frontpiece, by the renowned book illustrator Charles Edmund Brock. The costs of colour illustration had decreased significantly since the 1887 edition, and colour was now the norm for books for younger children. The following illustrations show the story in outline.

First

First Second

Second Third

Third Fourth

Fourth Fifth

Fifth Sixth

Sixth Seventh

Seventh Eight

Eight

See also

- Alice Meynell

- George Eliot

- Madonna/whore complex

- Ouida

- Romain Rolland

References

- Keegan Paul & Co has long ago been subsumed into Routledge.

- The British Library Catalogue shows that the 8º size book had 168 page in the 1887 edition and 175 in the 1909 edition.

- The edition with the illustrations by Paul Hardy is available on Project Gutenberg and elsewhere.

References

- I. Ousby ed., The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (1995) p. 594

- Schaffer, Talia (2010-05-21). "Lucas Malet Biography". English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920. 47 (3): 347–349. ISSN 1559-2715.

- "Obituary: "Lucas Malet": A novelist of Character". The Times (Thursday 29 October 1931): 14. 1931-10-29.

- "Literary Worlds > Lucas Malet". exhibits.lib.byu.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- "Harrison, Mary St. Leger". Who's Who. 59: 790. 1907.

- "Lucas Malet Orlando Project". orlando.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- P. L. Lundberg, An Inward Necessity (2003)

- Coustillas, Pierre ed. London and the Life of Literature in Late Victorian England: the Diary of George Gissing, Novelist. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1978, p.267 and 275.

- "in Malet's The Gateless Barrier, set at the end of the nineteenth century, the ghost of an eighteenth-century woman lives in "the yellow drawing-room..."Talia Schaffer, The Forgotten Female aesthetes : literary culture in late-Victorian England. Charlottesville : University Press of Virginia, 2000. ISBN 0813919363 (p. 98)

- T. Schaffer, The Forgotten Female Aesthetes (2000) p. 199

- P. L. Lundberg, An Inward Necessity (2003) p. 162

- Lundberg, Patricia Lorimer (2003). An Inward Necessity: The Writer's Life of Lucas Malet. Peter Lang.

External links

- Works by Lucas Malet at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Lucas Malet at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Lucas Malet at Internet Archive

- Works by Lucas Malet at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works at The Victorian Women Writers Project

- Lucas Malet at The Literary Encyclopedia

- Georgina Battiscombe, ‘Harrison , Mary St Leger (1852–1931)’, rev. Katharine Chubbuck, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004