Louis Riel Memorial (Nugent)

The Louis Riel Memorial[1] is a public sculpture by John Cullen Nugent that stood on the grounds of the Saskatchewan Legislative Building for a quarter of a century.[2] The original concept was commissioned as an abstract sculpture in steel, opposed by Premier Ross Thatcher, who insisted on a realistic depiction instead. The artist and the premier remained at odds over details until the eve of the work's unveiling. The statue was controversial, particularly with the Métis community, and was finally removed in 1991 at the long insistence of the Métis Society of Saskatchewan.[2]

| Louis Riel Memorial | |

|---|---|

| Artist | John Cullen Nugent |

| Year | 1968 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Subject | Louis Riel |

| Location | Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada |

Background

The idea for an official provincial memorial for Louis Riel originated in 1964 when the Government of Saskatchewan's Creative Activities Subcommittee planned a monument for the Métis leader erected in time for the celebrations of Saskatchewan's diamond jubilee in 1965, and asked Clement Greenberg for his opinion. Greenberg had spent a summer at a University of Saskatchewan painting workshop at Emma Lake, and suggested John Nugent, who had participated in such workshops in 1949.[3] A sculpture was never erected for the jubilee.

Nugent had begun his career as a proficient sculptor creating liturgical commissions in silver and bronze, but as of 1961, had gradually shifted to welded steel abstract sculptures.[4]

History

Commission

John Nugent[5]

In the lead-up to the Canadian Centennial in 1967, the Saskatchewan Arts Board recommended that the province should have a new public sculpture.[6] To this end, a competition was announced.[6] As the Centennial approached, with interest in First Nations peoples on the rise, Nugent was reading Joseph Kinsey Howard's Strange Empire (1952), a discussion of Louis Riel and his leadership of the Métis, which both moved and inspired him: he viewed Riel as someone ahead of his time, as important for the present and future as for the past.[note 1]

Abstract proposal

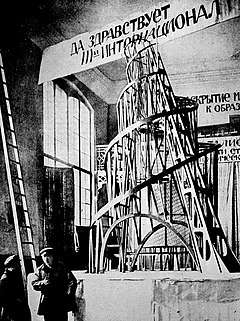

Nugent's submission was an abstract sculpture to have been made with twenty tons of heavy steel reaching up to thirty feet:[7] "two large plates of steel and a single spike between them",[6] intended to suggest "the soaring spirit and struggles of Louis Riel and the Métis."[note 1] The idea was to represent an as yet unrealized inspiration.[6][7] Maria Tippett compares it to a model of a welded steel tower by the Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin produced in the Soviet Union in 1920.[1] Will Chabun interprets the visual image as "two hands reaching out and one other element reaching out to the sky."[6]

Nugent's proposal won the competition, and Wilf Klein, Executive Director of the Centennial Comnmittee in Saskatchewan, asked the artist to create the sculpture for $10,000,[7][5] but Premier Ross Thatcher stepped in and made clear his preference for a realistic and "manly" depiction.[6][5] A provincial cabinet meeting followed which included Nugent, representatives from the Board and the University of Saskatchewan, and Art McKay. All were convinced of the proposal's merit except Thatcher, and his was the only view that mattered.[6]

John Nugent[5]

Figurative proposal and final work

Nugent created a second maquette, a sculpture of Riel "striding forward", arm raised and pointing upward, maintaining in some way the essence of the original idea,[6] albeit more explicitly: with his head and right hand thrust skyward, Riel is represented in a final act of defiance before the Métis surrendered to General Middleton at Batoche in 1885, of which Nugent said: "It was the ultimate humiliation for the Métis. When Middleton's army found them at Batoche, they had very little. No shoes or food."[8] This "heroic" figure of Riel was sculpted as a classical nude,[9][7] which Nugent thought appropriate as Riel is "a kind of classical tragic figure, a prophet frustrated in his grand design by petty politicians."[10]

While this was not exactly what Thatcher had wanted either (he would have preferred Riel in a suit), he nevertheless asked Nugent to go ahead with it, and Nugent was commissioned to create this version,[11] with the proviso that the statue be clothed. Nugent would later say he wanted to refuse but he needed the money.[6] The finished statue is covered in something variously described as a "cloak",[2] "mackinaw",[5] "cape or vest", made from wax-coated burlap wrapped around the statue's body, ostensibly to cover the genitalia, though it did not do so entirely.[6]

As for why Thatcher took such an interest in the sculpture in the first place, Frances Kaye's research has suggested that many in Regina believed the sculpture had been commissioned for purely political purposes: in doing so, he could present himself as a "friend" to First Peoples three weeks before an election in which he hoped to attract Métis, Non-Status, and First Nations support: "Whether or not Thatcher ever articulated the goal to himself, he seems to have understood that in his Riel - for he made it his Riel statue - he was reinventing the Indian... and setting him up as the bourgeois, Europeanized, assimilated man."[12]

Installation

Thatcher argued with Nugent over the height of the pedestal, the artist insisting that it be lowered before he would hand over the sculpture. With Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau making a special visit for the unveiling imminently, Thatcher had to give in.[10]

The unveiling took place on 2 October 1968, just north of the Legislature,[7] to a crowd of about three thousand, very few of whom were Métis.[13] Tributes were made to Riel by Thatcher and Trudeau, who praised him as a "fighter for his people," while Thatcher called him as "a brilliant figure, a man of exceptional leadership qualities, a man fiercely proud of his heritage."[13] Neither Nugent nor any representatives of either the Métis or First Nations were invited to speak.[7][10]

John Nugent[5]

Reception

Thatcher is reported to have been displeased with the statue itself, as it was discovered fairly quickly that the genitalia could be seen by "looking up" under the garment, and this became a source of local embarrassment[5] (and later, vandalism),[7] which Linda Mitchell called the sculptor's revenge.[5] Nugent was only paid half the sum he was owed as he owed $5,000 on a government loan he got to build his studio in Lumsden; he said he could not afford to sue over it.[5]

Response from the Métis community

Though Louis Riel was a leader of the Métis community, no Métis were ever consulted by those involved in the project at any stage.[6] Response from the community was mostly negative. In contrast to the statesmanlike treatment accorded European Canadian leaders like Sir John A. Macdonald in other public memorials, this one, they said, depicted its subject in a "disrespectful" manner: "gaunt" and semi-nude, in the moment of ultimate Métis humiliation.[14] While some found the work demoralizing for depicting that moment of history, others argued that the sculpture was Euro-Canadian appropriation.[13][15] The ArtsSask.ca website summarized Métis criticisms: "John Nugent was not of Metis descent and many people in the Metis community were upset because they had no input in the design. Many also found the sculpture of Riel offensive..."[6] Nap Lafontaine was delegated by the Métis Society of Saskatchewan to talk to Thatcher, who explained that the statue was "new art" and "that new art won't be appreciated for 50 years", to which Lafontaine quipped: "Appreciated! That thing won't be there that long."[13]

Response from the artist

Louis Riel did not enjoy the universal support of Métis in Saskatchewan in the 1880s,[16] and may not have been the best choice of subject for the purposes of celebrating their history, according to Nugent, who later said that Thatcher made a mistake by not consulting with the Métis community, and for his own part, took the view that a majority of contemporary Métis in Saskatchewan would have preferred a sculpture of Gabriel Dumont, Riel's military assistant during the Resistance of 1885, Riel being more of a symbol to Whites.[note 1] Thatcher's continuous interference with Nugent's work had the effect of distancing the artist from his own work: "It was a bit of a potboiler. I'd rather they just return it to me or move it out onto the lake ice in winter. Then in the Spring it would sink down along with all the controversy."[8]

Response from the wider community

Over the next twenty years, the sculpture was continuously denounced,[17] and pressure increased with time to remove the work from the legislative grounds.[18] When a decision was finally made about removing the statue, Euro-Canadian response was mixed. Its proposed removal ellicited some disappointed responses from members of the public identified as of European descent,[7][17] but an anonymous editorial in the Regina Leader-Post struck a conciliatory note: "If indeed such a move can overcome a slight against the Métis, who presumably are supposed to feel honoured, not humiliated by the Riel statue, the move has some merit."[19] Journalist Ron Petrie's opinion most closely reflected that of the Métis:

Imagine if you dare, the likely reaction of the Saskatchewan public if a statue of, say Tommy Douglas, John Diefenbaker or Ross Thatcher were unveiled in front of the Legislative Building and, like the Riel piece, portrayed the man with his genitalia exposed. The artïst would be run out of town, his body covered with black-and-blue welts, that's what would happen.[20]

Removal and relocation

In 1991, the sculpture was removed and relocated to the MacKenzie Art Gallery vaults,[2] along with Nugent's original abstract maquette, where it has remained,[6][21] apart from occasional exhibitions such as Timothy Long's A Canadian Dream: 1965–1970, which took place in 2017.[22]

Replacement

While it stood, the Métis Society had wanted to replace Nugent's work with a different statue of Riel, ideally by a First Peoples artist, but more importantly, that it should be "realistic, dignified, and respectful", so that Riel would be "recognized for the hero he is".[3] It was ultimately replaced, however, by a cairn commemorating Riel's trial, erected by the producer of the play The Trial of Louis Riel and the Chamber of Commerce.[12]

Note

- Related by Nugent in a 1998 telephone interview with Catherine Mattes.[7]

References

- Tippett, Maria (2017). Sculpture in Canada: A History. Madeira Park, B.C.: Douglas and McIntyre (2013). ISBN 9781771620932. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Kearney, Mark, and Randy Ray (1999). The Great Canadian Book of Lists. Toronto: The Dundurn Group. p. 53. ISBN 0888822138. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Draaisma, Muriel (9 August 1991). "Regina statue panned; so is version in Man". Regina Leader-Post.

- Long, Timothy. "John Cullen Nugent". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Mitchell, Linda (1 May 1969). "One sculptor's racy revenge with an embarrassingly real Riel". Maclean's: 2. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Chabun, Will (10 September 2016). "Icons in exile: How Regina's Riel statue and other monuments disappeared from view". Regina Leader-Post. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Mattes, Catherine L. (1998). "Chapter Two. The versatility of Riel". Whose Hero? Images of Louis Riel in Contemporary Art and Métis Nationhood (M.A. thesis). Montreal, Quebec: Concordia University. pp. 51–100. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Roberts, David (8 August 1991). "Scantily clad Riel to leave legislature". The Globe and Mail.

- "John Nugent". University of Regina Library. University of Regina. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Miller, Ross (2 October 1968). "Nugent sees Riel as a contemporary man". The Regina Leader-Post.

- Pincus-Witten, Robert (1983). John Nugent: Modernism in Isolation. Regina: Mackenzie Art Gallery. p. 22.

- Kaye, Frances (1997). "Any important form: Louis Riel in sculpture". Prairie Forum. 22 (1): 114.

- Pitsula, James M. (Summer–Fall 1997). "The Thatcher Government in Saskatchewan and the revival of Métis nationalism, 1964-71". Great Plains Quarterly (17): 213–235. Retrieved 10 January 2020.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Beatty, Greg (Winter 2003–2004). "Kim Morgan: Antsee. Espace Sculpture" (PDF). Erudit (66): 42. ISSN 0821-9222. Retrieved 10 January 2020.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Thraves, Bernard D., [and three others], ed. (2007). Saskatchewan: Geographic Perspectives. [Regina, Saskatchewan]: University of Regina Canadian Plains Research Center. ISBN 9780889771895. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Lee, David (1989). "The Métis militant rebels of 1885". Canadian Ethnic Studies. XXI (3).

- Walsh, Andrea N., and Dominic McIver Lopes (2009). "Objects of Appropriation". In Young, James O., and Conrad G. Brunk (ed.). The Ethics of Cultural Appropriation. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 214. ISBN 9781405161596. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Chabun, Will (19 March 2014). "Sculptor built solid reputation". Regina Leader-Post. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "[Editorial]". Regina Leader-Post. 3 August 1991.

- Petrie, Ron (3 August 1991). "It's about time this statue is moved to another place". Regina Leader-Post.

- Hamon, Max (20 December 2017). "[Book review] #226 Rescuing Riel, revising history". BC book look. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Beatty, Gregory (6 July 2017). "Strange Nation: A Canadian Dream shares art from our complex, conflicted country". Prairie Dog. Retrieved 14 January 2020.