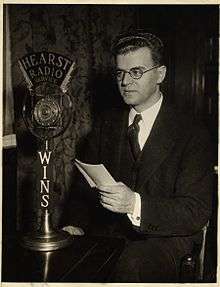

Louis Israel Newman

Louis Israel Newman was a prominent United States Reform rabbi and author.

Louis Israel Newman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 20, 1893 |

| Died | March 9, 1972 (aged 78) New York City, New York |

| Alma mater | Brown University (B.A.) University of California, Berkeley (M.A.) Columbia University (Ph.D.) |

Early life

Born in Providence, Rhode Island on December 20, 1893 to Paul and Antonia (née Hecker) Newman, Louis Israel Newman attended Brown University (B.A. 1913), and then went on to receive an M.A. from the University of California, Berkeley in 1917, and a Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1924. From 1913 to 1916 Newman served as rabbi of Congregation Beth Israel (Berkeley, California). In 1917, Newman became an assistant to Rabbi Stephen Wise at the Free Synagogue in New York City and then was ordained by Stephen Wise and Martin Meyer in 1918.

Career

After his ordination, Newman became rabbi of the Bronx Free Synagogue (1918–21).[1] In 1921, he became rabbi of Temple Israel in New York City and was appointed to the faculty of the Jewish Institute of Religion (JIR) when it was founded the following year.[2] In 1924, Newman moved to San Francisco, replacing Martin Meyer as rabbi of Temple Emanu-El.[3]

In 1930, Newman returned to New York City to become rabbi of Temple Rodeph Sholom.[4] He stayed in this pulpit until his retirement in 1972. During his tenure at Temple Rodeph Sholom, Newman became active in the Zionist Revisionist movement,[5] was the chairman of the Palestine Mandate Defense Fund, and was honorary chairman of both the Revisionist Tel Hai Fund and the American Friends of a Jewish Palestine.[6] He once again served on the faculty of the JIR. He also served on the American advisory committee for the Hebrew University and as a vice president of the American Jewish Congress.

Brandeis University

Newman was the visionary for Brandeis University. "To be sure, Rabbi Newman was not the first during the twentieth century to advocate for a Jewish institution of higher learning. [...] Yet, it was Newman's proposal, published in the Jewish Tribune, which inexplicably garnered the attention and raised the eyebrows of American Jewry. Rabbi Newman had firsthand knowledge of the Jewish quota, having attended Brown University at a time when the school's administration imposed 'limitations in the enrollment of Jews and Negroes.' Taking stock of the United States' 15,000 Jewish collegians—nearly ten percent of the total collegiate population—Newman lamented that 'the Jewish student is becoming more and more unwelcome in privately endowed American universities.' More significant than exclusion from academe, Newman worried about the very practical problem that, as a result of limited educational opportunities, American Jews were in jeopardy of being further rejected from 'higher spheres of the professions and commerce.'"[7]

There were many other proposals, but Newman continued steadfast in his work for his vision of a Jewish university. He published a slim volume, appropriately titled A Jewish University in America?,[8] featuring an expanded version of his original essay and a collection of the articles and letters that had appeared on the subject.

In 1945 Newman was recruited by Rabbi Israel Goldstein, to join a group of men to consider the possibility of opening a Jewish university in Waltham, Massachusetts, some ten miles northwest of Boston. For his obvious interest and expertise in the matter, Goldstein was delighted to "have the friendly support of Rabbi Louis I. Newman."[9]

Though Newman's did not remain on this board that would help in the founding of Brandeis, the school's first president, Abram L. Sachar, wrote to Newman, just three weeks before the start of the first semester. Sachar told Newman that he considered him to be "one of the most valued pioneers in the long battle to establish a university in America under Jewish auspices." And, "in a very deep sense we are indebted to you for preparing the soil and fructifying it," wrote Sachar. Yet, it was probably another line in Sachar's letter that properly represented Newman's bittersweet feelings on the matter. "It is too bad," Sachar sympathized, "that a generation had to pass before your vision was acted upon."[7][10]

Writings

Newman was a prolific writer and playwright. Some of his volumes include: Jewish Influence on Christian Reform Movements (1924) and Jewish People, Faith and Life (1957). He also compiled and translated the classic work The Hasidic Anthology, Tales and Teachings of the Hasidim: The parables, folk-tales, fables, aphorisms, epigrams, sayings, anecdotes, proverbs, and exegetical interpretations of the Hasidic masters and disciples; their lore and wisdom (1934, 1968, 1972), which has become a standard textbook for courses in Jewish studies.

Personal life

In 1923, Newman married Lucille Helene Uhry,[11] daughter of Edmond and Lillian (née Hessberg) Uhry. Together they had three sons, Jeremy Uhry Newman, Jonathan Uhry Newman, and Daniel Uhry Newman. Rabbi Louis Israel Newman died at the age of 78 on March 9, 1972 in New York City.[12]

References

- The American Jewish Chronicle. Alpha Omega Publishing Company. 1918-01-01.

- "Jewish Institute of Religion New York". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- Rosenbaum, Fred (2000-01-01). Visions of reform: Congregation Emanu-El and the Jews of San Francisco, 1849-1999. Judah L. Magnes Museum. ISBN 9780943376691.

- "Rabbi Newman Accepts Rodeph Sholom Call". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- Medoff, Professor Rafael (2006-10-15). Militant Zionism in America: The Rise and Impact of the Jabotinsky Movement in the United States, 1926-1948 (1 ed.). Tuscaloosa, AL: University Alabama Press. ISBN 0817353704.

- Baumel, Judith Tydor (2005-01-01). The "Bergson Boys" And the Origins of Contemporary Zionist Militancy. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630630.

- Eleff, Zev (2011-01-01). ""The Envy of the World and the Pride of the Jews": Debating the American Jewish University in the Twenties". Modern Judaism. 31 (2): 229–244. ISSN 1086-3273.

- Newman, Louis Israel (1 January 1923). "A Jewish University in America?". Bloch publishing Company – via Google Books.

- Goldstein, Israel (2007-03-01). Barndeis University - Chapter of Its Founding. Read Books. ISBN 9781406753912.

- Abram L. Sachar to Louis I. Newman, September 15, 1948, Louis I. Newman Papers, Box 11, Folder 6, American Jewish Archives.

- Nadell, Pamela S. (1999-10-01). Women Who Would Be Rabbis: A History of Women's Ordination 1889-1985. Beacon Press. p. 246. ISBN 9780807036495.

lucille%20helene%20uhry.

- "Louis I. Newman, Noted Rabbi 78". The New York Times. 1972-03-10. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-07-23.