Louis George

Louis George was a Prussian master watchmaker of the late baroque era.

.jpg)

Louis George was a descendant of French Huguenots living in Berlin in the third generation. Louis George produced mainly daedal watches. Reported makes are: pocket watches, nautical clocks, mechanical odometer, console clocks, long case clocks, dead second watches.

Working period

On the 26 December 1769 Louis George applied for the patent as the royal watchmaker and succeeded. He was allowed to call himself from now on “Horloger du Roy” — in English, "watchmaker to the king". French was the language of the Berlin nobility.

The literature on Louis George reports different working periods. The writer Gerhard Koenig states in his book a working period from 1769 to 1796. The address calendar of Berlin lists the Louis George in the editions of the years 1799 and 1801.

The addresses of Louis George's workshops mentioned at the Berlin Adresskalender are Schlossplatz 10 and 13 (in 1799) and Schlossplatz 10 in (1801), right opposite the Stadtschloss (city palace) of Berlin. Starting in 1815 Louis George et compagnie produced lever pocket watches, most probably a son of the royal watchmaker.

Watchmaker to the King

Louis George was a talented watchmaker and artist. He did not just create watches but real gems of watch making. His posh watches enchanted the audience and recovered the respect of the Berlin nobility and solvent bourgeoisie. His business flourished and he was capable of opening a second shop in the same street opposite the royal city palace.

Located at Berlin he provided watches for three generations of Prussians kings:

- Frederick II. (the Great) King of Prussia

- his nephew and successor Frederick William II. King of Prussia

- his nephew and successor Frederick William III. King of Prussia

Other German monarchs appreciated the masterly crafted clocks and watches too. A long case clock with an organ movement formerly owned by Georg I. Duke of Saxe-Meiningen is preserved on castle of Elisabethenburg at Meiningen. It can be visited at the art collection of the Meininger Museen at the Schloss Elisabethenburg Inventory-No. II 1908, height 2,93 m. approx. 1790; watch dial reads: „Ls. GEORGE HORLOGER DU ROY“ / „A BERLIN“. The curator M. Ruszwurm reports that clock is equipped with a precious flute watch (also called organ watch).

A console clock with an attached flute work is exhibited at the Schloss Sanssouci at Potsdam.

Louis George long case clock of Georg I. Duke of Saxe-Meiningen

Louis George long case clock of Georg I. Duke of Saxe-Meiningen Clock dial of a Louis George console clock at Sanssouci

Clock dial of a Louis George console clock at Sanssouci Louis George alcove clock with an attached bronze flute work, auctioned 2005 in Paris

Louis George alcove clock with an attached bronze flute work, auctioned 2005 in Paris- Table flute clock by Matthias Naeschke

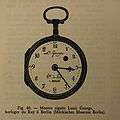

Louis George lever watch, face

Louis George lever watch, face Louis George lever watch, back

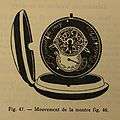

Louis George lever watch, back Louis George pocket watch, made in Berlin about 1810, photo: Dr.Ilk, Munich, Germany

Louis George pocket watch, made in Berlin about 1810, photo: Dr.Ilk, Munich, Germany Entry of the address of Louis George at the Berlin address book of 1769

Entry of the address of Louis George at the Berlin address book of 1769

European market

Louis Georges watches and clocks can be found all over Europe. A bedroom clock displaying hour, minute and date with a rich decorated and gold-plated case was auctioned in Paris in 2005. Other clocks made by Louis George have been found in Spain.

Louis George discussed technical problems of watchmaking with other watchmakers from the Swiss Canton of Neuchâtel. He had business connections with the Swiss watchmaker Pierre Jaquet-Droz and Jean-Frédéric Leschot. These watchmakers tried to find technical solutions going far beyond the requirements of ordinary watch making. Jaquet-Droz created mechanical puppet automats. Louis George created complicated clocks with an attached organ or flute work.

Berlin – the Baroque Hub of watchmaking

Berlin was considered a hub for the production of organ and flute clocks. The clock movements released an attached organ, flute or harp unit at a preset time – working like a music alarm clock.

Sites of historical Louis George Clocks

- Musée d´Art et d´Histoire, Geneve, Switzerland: Dead Seconds Watch (Inventory No. H2006-106)

- Schloss Sanssouci, Maulbeerallee, 14469 Potsdam, Germany

- Art collection of the Museums at Meiningen - Schloss Elisabethenburg, PF 100554, 98605 Meiningen, Germany

Bibliography

- Uhren und Uhrmacherei in Berlin 1450 - 1900 - Miniaturen zur Geschichte, Kultur und Denkmalspflege Berlins, Kulturband der DDR, Berlin 1988, by Gerhard König

- Abeler, Jürgen (1977). Meister der Uhrmacherkunst: Über 14000 Uhrmacher aus dem deutschen Sprachgebiet mit Lebens- oder Wirkungsdaten und dem Verzeichnis ihrer Werke. Uhrenmuseum.

- G. H. Baillie (2008). Watchmakers and Clockmakers of the World. Read Books. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-4437-3353-3.

- Chapuis, Alfred; Kehrli, Charles (1931). Pendules neuchâteloises: documents nouveaux. Slatkine. p. 113. ISBN 978-2-05-100819-8.

- Chapuis, Alfred (1980). History of the musical box and of mechanical music. Musical Box Society International. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-915000-01-2.

- Chapuis, Alfred; Droz, Edmond (1958). Automata: a historical and technological study. Éditions du Griffon. p. 199.

- Le Grand Frédéric et ses horlogers: une émigration d'horlogers suisses au XVIIIme siècle; un demi-siècle d'horlogerie berlinoise (1760–1810), by Alfred Chapuis, publisher: Journal suisse d'horlogerie et de bijouterie, 1938, page 64 and 65, illustration of a Louis George pocket watch

External links

- Louis George dead second pocket watch with Pouzait escapement exhibited at the 13e Journée d'étude de la Société Suisse de Chronométrie

- LOUIS GEORGE website

History

- Berlin address calendar of 1799 at the Historische Sammlungen of the Zentral und Landesbibliothek Berlin, Breite Str.36, 10178 Berlin, Germany

- Berlin address calendar of 1801 at the Historische Sammlungen of the Zentral und Landesbibliothek Berlin, Breite Str.36, 10178 Berlin, Germany

- Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein, Berlin - Berlin history web portal, registered association