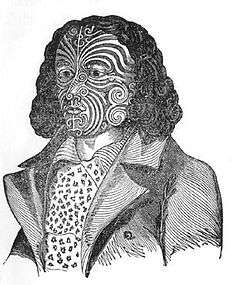

Louis Celeste Lecesne

Louis Celeste Lecesne (c. 1796 or 1798 – 22 November 1847), also known as Lewis Celeste Lecesne, was an anti-slavery activist from the Caribbean islands.

Louis Celeste Lecesne | |

|---|---|

Louis Celeste Lecesne | |

| Born | 1796 or 1798 Port au Prince or Kingston |

| Died | 22 November 1847[1] London |

| Education | Mr Goff's school in Kingston |

| Occupation | Victualler |

| Spouse(s) | Hannah Escoffery |

| Parent(s) | Charlotte Celeste Louis Nicholas Lecesne |

Lecesne was on a committee to improve the rights of free men of colour.[2] He was arrested twice, and transported for life from Jamaica with John Escoffery.[2] Their case was taken up by Dr. Stephen Lushington. Lecesne was compensated after successfully having the case reversed by the British government.[2][3]

Lecesne became an activist against slavery and attended the world's first anti-slavery convention.[4] He named his son after the British Member of Parliament who had fought for his case. Lecesne was a supporter when the 1839 Anti-Slavery Society was formed.

Disputed birth

Lecesne was the son of Charlotte Celeste and Louis Nicholas Lecesne, and was born in either Port au Prince or Kingston in 1796 or 1798. His mother and father had arrived in Jamaica on 25 August 1798 with a child called Figge.[5] Lecesne's father was French and had left St Domingo, whilst his mother was said to have African ancestry.[6] According to some, his mother was pregnant, Figge died and Louis was born. The Jamaican authorities believed however that Louis was the child who arrived on the brig Mary with his mother.

Lecesne's date of birth was given as 30 August 1798 in Kingston, but he wasn't baptised until 5 March 1814. His place and date of birth were the subject of later court cases. At these cases it was noted that Lecesne's mother and the midwife said that he was born a few months (or days) after their arrival in Jamaica.[5] Others disagree with this version as his mother said that when they arrived in Jamaica they did have a two-year-old child but he died just after the birth of this child.

Lecesne had two younger brothers Lamorette and Louis Nicholas Lecesne. His mother was manumised by Lescesne's father. The date of the birth was important as a later law gave privileges to children born on the island.[5]

He was taken to Mr Goff's school for "children of colour" in 1802 when his father asked for him to be given "the best English education". Mr Goffe signed an affidavit later to say that he thought Lecesne to be four years old at the time but others think this a very young age to send such a child to school in Jamaica.[5]

Others said that when Charlotte Celeste arrived she had a two-year-old son called Figge. They claim Lecesne was born in Port a Prince in St Domingo "opposite the post office".

When his father made a will and died in 1816 he made Lecesne his executor. Some claim that this means that his father knew he was 21 years of age, and therefore born before elsewhere.

Marriage

Louis Celeste Lecesne married Hannah Escoffery (born 15 November 1797 and also known as Anette), the sister of John Escoffery.[7][8]

At least three children were born to Louis Celeste Lecesne and Hannah Escoffery in Kingston. The first was Louise Amelia Lecesne (born 20 June 1817), followed by Elizabeth Adeline Lecesne (born 24 July 1818) and Celestine Aglaé Lecesne (19 June 1820 – 11 August 1821).[9] On 7 May 1823 Louis Celeste Lecesne was a witness to the marriage of his wife's brother, Edward Escoffery to Marie Montagnac in the Roman Catholic Church, Kingston.[10]

Lecesne and John Escoffery came to notice as members of a committee who were intent on changing the law such that free men "of colour" would be given free and equal rights to white people.[2]

Arrest

Louis Celeste Lecesne and John Escoffery were arrested on 7 October 1823 under the Alien Act by a warrant of the Duke of Manchester, the Governor of Jamaica. William Burge, the Attorney General, considered them to be of "dangerous character"; they were also considered to be aliens, because of claims that they were Haitian. Luckily they had time to raise a writ of Habeas Corpus in the Supreme Court of Jamaica[11]

While Lecesne and Escoffery were held in gaol, petitions made to the Governor were rejected as it was claimed that the signatories were all owed money by the accused. Later investigations showed that the largest debt involved was 25 pounds. After consideration by the judges, the two were released as they were considered to be British-born despite the arguments described earlier. Chief Justice Scarlett released them without bail as there were no charges.[2][11]

Later, a member of the House of Representatives moved that a secret committee be formed to look at this case. This man, Hector Mitchell, was made the chair of this committee, comprising three others including the Mayor of Kingston. Their investigations resulted in the forced exile of Lecesne and Escoffery to St Domingo. It had been said that Lecesne had sold arms to an insurrection in St George and that the two of them kept correspondence with people in Haiti for treasonable purposes.[11]

Having been separated from their families and possessions, the pair had to sell their watches and with this money and the help of British people on the island they set out for England.[11] With Lecesne and Escoffery deported, the free coloureds movement did not collapse in Jamaica. Instead, other campaigners, such as Edward Jordon, Robert Osborn (Jamaica), and Richard Hill (Jamaica) continued to agitate for equal rights for free coloureds, and they were finally successful when the Jamaican Assembly passed legislation allowing them to vote in elections and run for public office.[12]

A young English sailor boy, Barnet Burns, had been found ill in Jamaica and was cared for by Lecesne and his family. Following the deportation of Lecesne, Burns followed Lecesne's family to London, where he received an education under the patronage of Lecesne.[13]

England

The case of Lecesne and Escoffery was raised in the House of Commons by Stephen Lushington who was a known abolitionist and anti-slavery campaigner. Lushington spoke to the house on 16 June 1825. This resulted in a number of publications:

- Debate in house of commons 16 June 1825 regarding deportation of two persons of colour [14]

- A Reply to the Speech of Dr. Lushington, in the House of Commons by Mr Barret of the House in Jamaica, 1828[15]

There was a libel case against John Murray, not because he was the author, but because he was the publisher of a book that libelled Lecesne and Escoffery.[6] The case was based on the fact that the book recorded that the politicians in Jamaica considered Lecesne and Escoffery guilty of a criminal conspiracy. This case was held in Britain in order that it should not be biased.[2] If they were guilty of a conspiracy, then under the 1818 Alien Act they could be transported for life if they were born elsewhere.

The book concerned was "The annals of Jamaica, Volume 2" by the Reverend George Wilson Bridges. Bridges combined leading worship at St Annes and speaking up for the value of slavery.[16]

The libel case was successful and Lecesne was therefore innocent. Parliament ruled that they should both be allowed to return and be given compensation.[2]

Lecesne believed in the law. In 1832, Lecesne was living in England at the Fenchurch buildings in Fenchurch Street, London and on 26 June while walking outside his residence Lecesne was the victim of a pickpocket, Thomas Fielder, who had stolen a handkerchief. For this crime, Fielder, aged 15, was sentenced to transportation for life.[17]

Lecesne was on the board of the Anti-Slavery Agency in 1832 with other notable abolitionists such as William Allen, Zachary Macaulay, Robert Forster, George Stacey and Josiah Forster[18]

Louis Celeste Lecesne and his wife had a son whilst they were in London whom they christened Stephen Lushington Macauley Lecesne. He was born on 6 March 1834 and was christened at Saint Matthew Church, Bethnal Green, London, on 25 June 1834.[19]

In July 1838, Lecesne was one of the supporters of a campaign to raise a monument to Zachary Macaulay in Westminster Abbey.[20][21]

1840 Anti-Slavery Society convention

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

npgwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

On 17 April 1840, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society was formed to campaign for worldwide abolition of slavery. A short time later, the first World Anti-Slavery Convention was held in London, attracting an international participation. Lecesne attended the convention and is depicted in a painting The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840 by Benjamin Haydon(1841).[4]

According to a record at the Montserrat (West Indies) National Trust from the Official Assignee to the President Administering the Government William Shiell, Lescene was declared bankrupt in 1845; the Island Secretary Henry Loving apparently owed Lescene £198 12s 3d.[22]

Following a bout of pneumonia, Louis Celeste Lecesne died on 22 November 1847 at his residence at the Fenchurch buildings, Fenchurch Street in London.[1] At the end of May in 1848, The Times announced the sale of the "superior" effects of the late L. C. Lecesne Esq including his mahogany four poster and a six octave pianoforte.[23]

References

- Death Certificate, 22 November 1847, South East Sub-district in the City of London

- Monthly Comments, Jamaica Archived 21 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Ansell Hart, Volume 5. (August 1962 – July 1964), accessed September 2009

- Seizure and Imprisonment in Jamaica— Petition of L.C.Lecesne and J.Escoffery, Hansard, 21 May 1824, vol. 11 cc796-804, accessed 9 October 2008.

- The Anti-Slavery Society Convention, 1840, Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1841, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG599, Given by British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society in 1880.

- Letter to the Right Honorable Sir George Murray Relative to the Deportation of Lecesne and Escoffery from Jamaica, William Burge, 1829, accessed 8 October 2008

- Full text of "Report of the trial of Mr. John Murray: in the Court of King's Bench, at Westminster-Hall, the 19th December, 1829, on an indictment for a libel of Messrs. Lecesne and Escoffery, of Jamaica" , archive.org, accessed 11 October 2008.

- Various Escoffery family reports, from Anglican and Roman Catholic Registers

- B0089 Kingston Anglican Parish Registers VI and Burials I & II, II, p. 281, Name listed as "Jane M." in Registrar's Copy Register.

- B0089 Kingston Anglican Parish Registers VI and Burials I & II, II, p. 405.

- B0064 Roman Catholic Marriages 1802-1839, pp. 83-84.

- The Anti-slavery Reporter, Zachary Macaulay, Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery, pp. 27-31,accessed 12 October 2008

- C.V. Black, A History of Jamaica (London: Collins, 1975), p. 183.

- Barnet Burns, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, accessed 25 January 2009.

- Bibliographia Jamaicensis, by Institute of Jamaica Library, Frank Cundall

- A Reply to the Speech of Dr. Lushington, in the House of Commons on the state of the people of Jamaica, by Mr Barret of the House in Jamaica, 1828.

- The annals of Jamaica, Volume 2, George Wilson Bridges, Pub. John Murray (III), accessed September 2009

- Proceedings of the Old Bailey, Thomas Fielder, Theft, pocketpicking, 5 July 1832, Reference Number t18320705-19, www.oldbaileyonline.org, accessed 7 September 2009.

- The Baptist Magazine, p. 353, 1832, accessed 11 October 2008.

- Birth record of Stephen Lecesne, FamilySearch.org, accessed 1 October 2008.

- Other signatories included Stephen Lushington Macaulay Lecesne who also made a contribution, confirming that his son was named for this Macauley.

- The Times, Tuesday, 4 September 1838.

- Montserrat Register of Deeds 1844-47 p.378

- Superior Household Furniture, Linen, Glass.... , The Times, 1848, Wednesday 31 May.