Loss of MV Darlwyne

MV Darlwyne[n 1] was a pleasure cruiser, a converted Royal Navy picket boat, that disappeared off the Cornish coast on 31 July 1966 with its complement of thirty-one (two crew and twenty-nine passengers including eight children). Twelve bodies and a few artefacts were later recovered, but the rest of the victims and the main body of the wreck were never found.

.jpg)

Built in 1941, after ending its naval service in 1957 Darlwyne was used as a private cabin cruiser, first on the River Thames and later in Cornwall, where it became a commercial passenger boat, despite being unlicensed for such work. It underwent considerable structural modifications, including the removal of its original watertight bulkheads and the conversion of its aft cabin into a large open cockpit. These changes adversely affected its seaworthiness. Surveyors' reports in 1964 and 1966 indicated that Darlwyne was unfit for the open sea; furthermore, it carried no radio or distress flares, and its lifesaving aids were rudimentary.

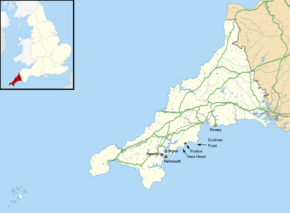

By 1966 Darlwyne was in the ownership of John Barratt of Penryn in Cornwall. The fatal voyage was arranged when the boat's skipper, Brian Bown, agreed to take a group of guests from the Greatwood guest house in Mylor on a sea trip to Fowey. On the morning of 31 July the outward voyage was completed without mishap, but the weather subsequently deteriorated. Bown disregarded advice to remain in Fowey harbour, and shortly after 4:00 pm began the return trip to Mylor. An unconfirmed sighting at around 6:00 pm placed the boat, in worsening conditions, in the vicinity of Dodman Point, a prominent coastal feature. Following its failure to arrive at Mylor the alarm was raised early on 1 August, and full air and sea searches began at dawn. After the recovery of 12 bodies, searches continued intermittently for several months, without finding traces of the vessel.

A Board of Trade enquiry into Darlwyne's loss placed the main blame on Barratt and Bown for allowing the vessel to go to sea in an unsafe and unprepared condition. Bown was lost in the disaster; Barratt was censured and ordered to contribute £500 to the cost of the enquiry. The Board's report exposed the laxity with which boat licensing regulations were being administered, and led to stiffer penalties for non-compliance, but there were no immediate regulatory changes, and no criminal proceedings were recommended. In April 1967 a memorial screen, listing the names of the 31 dead, was dedicated in Mylor church at a special service led by the Bishop of Truro. In 2016, on the 50th anniversary of the sinking, divers found an anchor and other debris at a location close to Dodman Point, which they stated were in all probability Darlwyne relics.

Vessel history

Construction

Picket boat no. 41768, the future Darlwyne, was built for the Royal Navy in 1941 in the Sussex Yacht Works yard at Shoreham-by-Sea.[2][3] The hull, carvel built from African mahogany and rock elm, was 45 feet (14 m) long, approximately 11 feet (3.4 m) wide, with a draught at the stern of 3 feet (0.91 m). Bulkheads divided the hull into fully watertight compartments, each equipped with a bilge pump. The vessel's original engine power was provided by twin Gardner 6LW diesel engines, each developing 95 horsepower.[3] It was built to operate in harbours and estuaries, mainly in transferring personnel between ship and shore, rather than for the open sea.[2]

1941–1964

The vessel remained with the Royal Navy until 1957, when it was sold to the Belsize Boatyard in Southampton. Here, it was converted to a cabin cruiser, during which most of the original bulkheads were removed; the replacements were not watertight.[4] In September 1959 the boatyard sold the boat to joint owners Messrs Lowe and Gray, who replaced the engines with less powerful twin Perkins P6 units each generating 65 hp. They then moved the boat to Teddington on the Thames, where on 22 April 1960 it was registered as a river cruiser under the name Darlwyne. At this time its gross register tonnage was recorded as 12.35.[2][4]

In October 1962 the owners transferred Darlwyne to St Mawes, in Falmouth Harbour, Cornwall. It was taken there by a crew of six; although the sea trip was accomplished without any serious incident, the crew were critical of the boat's performance in certain weather conditions. They found it top-heavy, difficult to steer, and with a tendency to list.[2] Darlwyne remained at St Mawes until September 1963, when the owners decided to sell it as a potential commercial passenger boat. At Mylor, in the Carrick Roads estuary of the River Fal, it was inspected by a local marine surveyor, George Corke. He noted the poor steering—it was impossible, he said, to navigate a straight course—and thought that much work would be necessary before it was fit for passenger-carrying operations. On 30 May 1964 Corke acted as agent for Lowe and Gray in the sale of Darlwyne to John Barratt of Penryn, whose main objective was to renovate the vessel with a view to a profitable sale.[5]

In Cornwall

After extensive work and repainting, in September 1965 Barratt agreed to sell Darlwyne to Steven Gifford, who took possession and began further adaptations. The sale ultimately fell through, and by the end of the year the vessel had been returned to Barratt.[6] In the spring and early summer of 1966, under the supervision of Barratt's daughter, further substantial alterations were carried out, including the removal of the aft cabin to create an open cockpit area. This work, undertaken without professional advice, was never fully completed.[7] During this period the boat was in regular use for trips by members of the Barratt family, including a Whitsuntide voyage across Falmouth Bay to the Helford River, where it apparently performed well in strong winds.[8]

At the beginning of July 1966, Darlwyne made several commercial sightseeing trips around Falmouth Harbour during Falmouth's Tall Ships regatta. A passenger on one of these sorties was Brian Michael Bown, a former member of the RAF Marine Rescue Section. Although not formally qualified as a ship's master, Bown had sailing experience and had skippered boats on seagoing trips to Fowey and the Isles of Scilly.[9] Subsequently, Bown suggested to Barratt a business venture in which Darlwyne would be used as a day-trip boat. Bown's letters indicate that he was proposing to work as the boat's skipper, and to take a third share of the profits.[10] Barratt's daughter advised Bown that they were preparing Darlwyne as "a twelve-passenger charter boat"; any number in excess of 12 would mean conforming with tougher Board of Trade regulations, and licensing might prove difficult.[11] According to Barratt, Bown was to assume responsibility for obtaining whatever licences were necessary.[12] Barratt later claimed that Bown had bought the boat outright, but there is no documentation of this supposed purchase, nor did Barratt mention it to anyone else.[13]

On 20 July 1966, at the request of Barratt's daughter, Darlwyne was again examined by George Corke, who found the boat in generally poor condition.[14] Among the faults he listed were dry rot, a weakening of the hull caused by the removal of various supporting frames, and signs that the hull had been "pushed in" below the waterline. Corke's report reiterated his earlier view that Darlwyne was presently unfit for work in the open sea. This report was sent not to Barratt but to the family's solicitors, where in the days that followed it lay unread; there is no indication that Barratt was aware of its contents before 31 July.[15]

Disaster

Plans

Robert Rainbird, proprietor of the Greatwood guest house at Mylor Creek, near Falmouth, was familiar with Darlwyne, having cruised with Bown in one of the earlier Tall Ships sailings. According to his later account, when two of his guests asked him about the possibility of organising a sea excursion, he put them in touch with Bown. On the evening of Saturday 30 July, amid celebrations following England's victory in the 1966 FIFA World Cup Final, Bown and his friend Jeffrey Stock, a qualified engineer, visited Greatwood. They found that enthusiasm for a sea trip had spread to many of the guests, and an agreement was made to take a large party to Fowey the following day. Different accounts were given later of the financial basis for the proposed hire – whether it was to be a fixed charge or a rate per head is uncertain.[16][17]

Barratt, the boat's legal owner, professed ignorance of the arrangements made at Greatwood, believing, he said, that Bown had gone there to discuss with Rainbird future charter work once the necessary licences had been obtained.[18] Under local regulations, a licence for carrying up to 12 passengers was subject to examination of the boat by the harbourmaster, who would also require the person in charge to be a licensed skipper.[19] Vessels proposing to carry more than 12 passengers needed a licensed master, a qualified marine engineer, and a Class III Passenger Certificate from the Board of Trade. This certificate was only granted to vessels in good condition with watertight hull compartments, a two-way radio, a qualified radio operator and a range of safety devices.[20] Darlwyne had no radio, no distress flares, and carried only two lifebelts.[21][n 2] Bown had apparently begun enquiries with the Falmouth Harbour Commission, but neither he nor Darlwyne possessed any of the licences needed for the boat to operate commercially.[22]

Voyage, 31 July 1966

In accordance with the arrangement made the previous day, early on Sunday 31 July Bown and Stock brought Darlwyne to Mylor Creek. The Greatwood party comprised, in all, twenty-six guests, one member of staff on her day off, and two children of another staff member. Eight of the party were children. Darlwyne anchored offshore, and the passengers were rowed out in two dinghies, one of which was hauled aboard and stored on davits, the other attached by a painter to Darlwyne's stern.[16]

BBC weather forecasts for the Cornwall area, broadcast the previous evening and earlier that morning, were discouraging; all promised increasing winds, up to Force 7, with the probability of rain from midday. Such weather conditions could produce heavy seas and poor visibility.[23] Nevertheless, Darlwyne set out from Mylor shortly after 10:00 am in pleasant sunshine, expecting to return before 7:00 pm. The journey to Fowey, which included a slight detour to view Mevagissey harbour, was completed without incident, and the party arrived in Fowey just after 1:00 pm. By this time the weather had deteriorated, and it was raining heavily. Bown did not tie up to the main town quay – he was heard saying that the vessel was "a bitch to handle" – and anchored mid-harbour, again using the dinghies to land the party.[24]

After three hours in the town, the group reassembled at the quay to be ferried back to Darlwyne. The wind was rising; a bystander heard a local fisherman advise Bown not to leave the harbour until the weather improved, but the warning was brushed aside.[23] Darlwyne sailed at approximately 4:10 pm,[n 3] and headed westward into the worsening weather.[25] For the first few miles the large headland known as Dodman Point would provide some shelter; thereafter the vessel would be fully exposed to the force of the winds.[26]

There were several possible sightings of Darlwyne on its homeward voyage. Outside Fowey Harbour in the vicinity of the Cannis Buoy a fisherman watched a vessel towing a dinghy pass by; soon afterwards another fisherman saw a boat off Meanease Point, close to Dodman Point, but did not notice a dinghy being towed astern. At about 5:45 pm a farmer whose land overlooked the sea to the west of Dodman Point saw a launch running close to Hemmick Beach, moving westward. He could see people in the stern area, and there were no evident signs of distress. A short while later an observer in the village of Portloe saw a cabin cruiser somewhere between Dodman Point and Nare Head, moving in the direction of Falmouth. This was the last recorded possible sighting.[27][28] By this time winds had strengthened to Force 6, with waves reaching 2 metres (6.6 ft) amid increasing rain and flying spray.[26]

In the late afternoon a holidaymaker reported seeing four people apparently stranded on Diamond Rock, a semi-submerged reef off Porthluney Cove, west of Dodman Point. The police were informed, but at that time Darlwyne was not overdue, and thus there was no reason to connect these people with those on the boat. This incident was not referred to in the subsequent searches, nor in the later Board of Trade enquiry which fixed the most likely time of sinking much later in the evening.[29]

Raising the alarm

At around 7:00 pm, Barratt's son-in-law Christopher Mitchell noticed that Darlwyne had not returned to its Penryn moorings. Having ascertained that the vessel was not at Greatwood House, Mitchell asked for news at the Falmouth coastguard station shortly before 7:30. The duty coastguard, Seagar, had no record of Darlwyne's departure that morning, and was unaware of its whereabouts. At this time there was no particular cause for alarm, and Seager did not record the enquiry. Mitchell assumed the boat might be sheltering in a harbour or estuary, but further enquiries among local acquaintances brought no further information.[30]

Later that evening, Rainbird telephoned Seagar and expressed concern at Darlwyne's non-arrival. As the call was not recorded, its timing is uncertain; it may have been around 8:00, but possibly as late as 9:30. Seager advised Rainbird to contact the coastguard stations on the Fowey–Falmouth route for news of Darlwyne, and asked him to report back any information. From his enquiries Rainbird established from the Polruan station that Darlwyne had left Fowey shortly after 4:00 pm that afternoon. He later claimed that he had passed this information to the Falmouth coastguards at about 10:15 pm. Seager denied receiving any such call before his duty stint ended at 11:00 pm, and did not mention the concerns about the missing Darlwyne to Coastguard Beard, his relief.[31] Beard heard of the likely emergency for the first time at 2:45 am on Monday 1 August when Rainbird, by now seriously worried, rang the coastguard station. Beard then informed his district officer, who authorised a full-scale coastal search for the missing vessel to begin at daybreak.[32]

Searches

At 5:34 am on Monday 1 August a warning message to shipping in the area was broadcast by the BBC. At 5:37 the Falmouth lifeboat was launched, followed a few minutes later by the Fowey lifeboat. At 6:45 a coastguard helicopter began a coastal search between Fowey and Falmouth, covering a distance of five miles out to sea. It was joined at 9:45 by an Avro Shackleton aircraft supplied by the RAF Search and Rescue Force, which extended the search area further south, west and east. Later, two Royal Navy ships, HMS Fearless and HMS Ark Royal, participated in the sea search.[33] At about 1:25 pm the tanker Esso Caernarvon found the dinghy that had been towed by Darlwyne, about 20 miles (32 km) south of Dolman Point and about 9 miles (14 km) from the Eddystone Lighthouse. The dinghy, empty but undamaged, was picked up by an RAF launch and brought to Falmouth.[34]

Amid rising anxiety ashore, there was still hope that Darlwyne remained afloat. Barratt's daughter believed the vessel to be "completely seaworthy",[35] while Rainbird surmised that it might have drifted southwards, out of fuel or with incapacitated engines, towards the Channel Islands. The coxswain of the Fowey lifeboat said, after 15 hours of searching, that "there was nothing to suggest that a boat had been wrecked out there".[36] Others were more sceptical: Steve Gifford, who had briefly owned the boat, was appalled that 31 people were aboard a vessel that was simply not strong enough to meet the heavy seas it must have encountered, and thought it likely she would have broken up and sunk very quickly.[37] This view was shared by Corke, the surveyor, who felt that Darlwyne was not seaworthy for the weather conditions that developed while it was at sea.[35]

Peter Bessell, House of Commons 3 August 1966.[38]

Searches by helicopter, Shackleton aircraft and lifeboats continued on 2 August, but were called off around mid-day due to poor visibility and adverse weather conditions. At the insistence of Rainbird, who argued that there was as yet no direct evidence that Darlwyne had sunk, the searches were resumed that evening. They continued into the following day, when they were joined by three de Havilland Dragon Rapide aircraft, privately hired by friends of one of the missing families.[39] The Rapides covered a sea area of 2,500 square miles (6,500 km2), extending to the Channel Islands, before returning to Cornwall on 4 August without finding any trace of the missing vessel.[40][41]

Darlwyne's possible fate was raised in the House of Commons on 2 August when members, while expressing the hope that survivors would be found, were concerned about the apparent lack of enforcement of regulations that should have prevented an overloaded, unlicensed craft from putting out to sea.[42] The following day, the Cornish MP Peter Bessell was highly critical of the delay in commencing the search until long after it was clear that Darlwyne was overdue. He cited "expert opinion" that the craft was in all probability still afloat, and described the search activity thus far as "totally inadequate". This allegation was strongly denied by the Air Force minister Merlyn Rees, who maintained that there had been no lack of urgency and that everything possible had been and was still being done.[43]

Victims

On 4 August the first victims from Darlwyne were discovered in the sea about four miles east of Dodman Point. The bodies were of Albert Russell, his wife Margaret, and two teenage girls: Susan Tassell and Amanda Hicks. The first three were brought ashore by the Falmouth lifeboat, the fourth by the Fowey lifeboat.[44][n 4] On 5 August the body of Jean Brock was found, wearing a lifebelt, six miles west of the Eddystone lighthouse.[44] That same day, light wreckage—planking from the on-board dinghy, an engine cover, a plastic ball and some sun tan lotion—was found on a beach near Polperro.[46][47]

On 8 August two more bodies—Margaret Wright and Susan Cowan—were found about eight miles from the Eddystone Lighthouse. Patricia Russell and Eileen Tassell were found two days later, off Looe Island and the Mew Stone respectively. The body of nine-year-old Janice Mills was washed ashore at Whitsand Bay on 11 August, and that of her eleven-year-old brother David was discovered at Downderry Beach, between Fowey and Plymouth, on 13 August. The twelfth and final body to be recovered was of Arthur Mills, found in the sea about 10 miles south of Plymouth.[44]

The subsequent post-mortems established that all the victims had drowned in deep water, suggesting that they had gone down with the vessel rather than after struggling on the surface.[48] An analysis of the times shown on various watches found on the victims suggested that the sinking had probably taken place around 9:00 pm on 31 July, and thus that Darlwyne was afloat for around three hours after the last tentative sighting.[49][n 5]

When the first bodies were brought into Falmouth by the local lifeboat, the quays were lined with hundreds of people who watched in silence as the victims were landed and taken away in hearses. All commercial activity in the harbour was suspended; the royal yacht Britannia, at anchor on a visit to the port, removed its ceremonial bunting and dipped the White Ensign as a mark of respect. The crowds returned to the harbour on 7 August for the town's annual lifeboat service; that year the occasion became a memorial service for Darlwyne's lost party.[46]

In the days and weeks that followed, relatives and friends of the victims took the bodies for private burial and collected the abandoned belongings from Greatwood. The sea search for the Darlwyne wreck continued through the autumn and winter and into 1967, led by HMS Iveston. This navy minesweeper, equipped with the latest sonar equipment, carried out exhaustive searches in the area around Dodman Point, thought to be the vessel's most likely resting place. Although more than 600 dives were carried out, no sign of Darlwyne was discovered.[51] In December 1966 the navy storeship HMS Maxim investigated the seabed around Looe, after reports that a trawler had caught on an unidentified object and lost its nets.[52]

Board of Trade enquiry

The Board of Trade court of enquiry into the loss of the Darlwyne began at the Old County Hall, Truro on 13 December 1966.[54] It sat until 6 January 1967, and published its findings in March of that year.[55] It was unable to determine who was responsible for organising the fatal trip, as most of those involved had lost their lives in the disaster. Barratt claimed ignorance, and Rainbird denied any role in the matter beyond introducing Bown to the guests who had asked about a sea trip.[56] In the absence of direct evidence to the contrary, the court assumed that details had probably been finalised in the Greatwood bar, between Bown and the two guests who had initiated the request.[17]

The court established that at the time of the disaster, neither Darlwyne nor Bown were licensed in terms of either Board of Trade or local regulations for passenger-carrying vessels.[52] The court believed that both Barratt and Bown were broadly aware of licensing requirements, but had taken few or no practical steps towards compliance by 31 July.[57]

Evidence of Darlwyne's history confirmed Barratt as its legal owner.[17] The court noted the general state of the vessel and the various alterations that had been carried out, affecting its seaworthiness. In particular, the cockpit floor was not watertight and had inadequate scuppers, so that water entering the cockpit drained into the lower hull rather than back into the sea. Lacking watertight bulkheads, the hull would easily flood with any rapid ingress of water. The hull itself showed evidence of dry rot and other external damage.[58] Poor communication between the various parties concerned with the vessel in the preceding months meant that these various shortcomings had been overlooked or ignored.[59] Furthermore, the overloading of the vessel with 31 people meant that it lay low in the water, so that a modest heel of 30 degrees would allow water into the open cockpit.[58]

The court heard details of Darlwyne's departure from Fowey, the prevailing weather conditions on 31 July, and the subsequent possible sightings.[60] It thought it likely that some time after 6:00 pm the engines failed, leaving the vessel to drift helplessly. Without radio or flares, Bown would have been unable to signal its distress. From the evidence of the stopped watches and the pathologist's reports of death by drowning in deep water, the court decided that it was likely that, around 9:00 pm, Darlwyne had been overwhelmed by heavy seas. Because of its structural faults it had filled with water and sunk rapidly, taking the entire complement down.[61]

Different testimonies were given about the number and timing of phone calls to the Falmouth coastguard station on the evening of 31 July, giving rise to a view that searches could have begun earlier.[62] The court strongly recommended that in future, all messages received by coastguard stations relating to vessels should be recorded and logged.[63] It was, however, satisfied that all searches had been thoroughly carried out.[64] It did not feel that the supposed delay in beginning the searches was significant, as there was no information available that would have justified action before 9:00 pm, by which time the disaster had in all probability already happened.[65]

In determining responsibility for Darlwyne's loss, the court was "satisfied that the major cause of the disaster was the Darlwyne going on a voyage to sea when she was physically unfit to withstand the normal perils which she might expect to meet".[66] Culpability was shared between Bown and Barratt, the former for taking passengers to sea in an unfit boat, the latter for failing to warn his "agent or servant" of the vessel's unfit state. Barratt was severely censured by the court, and ordered to pay £500 towards the cost of the enquiry.[66] Barratt considered the court's findings as related to him were "rather unfair", while Bown's widow defended her late husband as a competent and experienced skipper. Rainbird declared himself vindicated.[67]

Aftermath

On 9 April 1967, at the parish church of St Mylor, the Bishop of Truro led a service of dedication for a memorial screen, erected in the church to commemorate the victims of the Darlwyne disaster. The screen, designed by John Phillips and fashioned from oak by local craftsmen, contains the names of all the lost 31.[68]

After the Board of Trade report was published, the coroner reopened the inquests, which had been adjourned pending any recommendations from the enquiry for criminal proceedings. No criminal responsibility was established; verdicts of death by misadventure were recorded in each case. The coroner expressed the wish that, as a result of the tragedy, regulations concerning licences would be much more strictly enforced.[69] In this he echoed the Board of Trade report, which had stated that regulations relating to boat licensing "date from the Victorian era", and were wholly inadequate in modern conditions.[70] The Falmouth harbourmaster had told the enquiry that, without further staff, it would be impossible to check all the boats in the harbour; furthermore, he said, the £5 maximum fine for operating an unlicensed boat was not a deterrent.[52] In Parliament on 15 March 1967 the trade minister Joseph Mallalieu said that he had no plans to introduce further legislation for the licensing of pleasure boats plying for hire, but proposed to increase the penalties for infringement of existing regulations.[71]

Although the tragedy was keenly felt in Cornwall, its national impact, given the heavy loss of life, was relatively small, perhaps because it occurred during the post World Cup euphoria when public attention and headlines were directed elsewhere.[72][73] No clues to Darlwyne's fate emerged for decades. In July 2016, divers working with a BBC documentary team investigating the tragedy examined seabed locations closer to Dodman Point than the original searches.[74] According to local fishermen, debris had been recovered from this area in the 1980s, including a wooden transom bearing the name Darlwyne.[72] After several searches that revealed nothing, the 2016 divers found artefacts including an anchor, a winch, items of ballast, and the remains of a davit. No other recent wrecks or disappearances had been recorded in the area. "Taking everything into account", the divers reported, "it’s likely that what we found was what was left of the Darlwyne".[72][75] On this basis several media sources reported that the mystery had been solved.[73][76]

The lost

The victims, with their ages, are listed by Martin Banks in his 2014 history of the event as follows:[77]

Crew

- Brian Michael Bown (age 31) (skipper)

- Jeffery Claude Stock (age unknown) (engineer)

Passengers

- Lawrence Arthur Bent (74), Kathleen Bent (60), George Lawrence Bent (20)

- Roger Duncan Brock (26), Jean Brock (24)

- James Cowan (52), Dora Cowan (48), Susan Cowan (14)

- Mary Rose Dearden (19)

- George Edmonds (45)

- Amanda Jane Hicks (17), Joel Hicks (9)

- Arthur Raymond Mills (42), Jonathan David Mills (11), Janice Beverley Mills (9)

- Kenneth Arthur Robinson (19)

- Patricia Roome (48)

- Albert Russell (50), Margaret May Russell (50), John David Russell (21), Patricia Ann Russell (19)

- Peter Lyon Tassell (41), Eileen Sybil De Burgh Tassell (41), Susan Gail Tassell (14), Nicola Sara Tassell (12), Frances Harriet Tassell (8)

- Lorraine Sandra Thomas (20)

- Malcolm Raymond Wright (26), Margaret Wright (22)

Notes and references

Notes

- Early press accounts of Darlwyne's loss spell the name as "Darlwin". This spelling was used in posters advertising the boat's availability for charter, which its owner John Barratt had printed shortly before the disaster.[1]

- The 1967 Board of Trade enquiry report listed the equipment believed to be on board Darlwyne on 31 July 1966: Two fire extinguishers, two anchors, various ropes, two lifebelts, two non-inflatable lifejackets, compass, binnacle, dinghy in davits, towed dinghy, petrol-driven bilge pump, hand bilge pump, various tools, charts. It noted the absence of flares or buoyancy apparatus.[21]

- The time is that given in the Board of Trade report 1967.[25] Banks 2014 gives a later departure time of 4:45 pm.[23]

- In 2016, a member of the Falmouth lifeboat crew recalled seeing another body in the water which, however, sank before it could be recovered.[45]

- Six watches were recovered. The latest stopped times shown were 9.17, 9.19, and 9.49. Tests on watches of similar calibre indicated that the first two would have stopped after 10–25 minutes immersion in water, the third after about an hour.[49] Banks writes: "It is uncertain what happened to the Darlwyne between 6:00 pm and 9:00 pm".[50]

Citations

- The Guardian 7 August 1966.

- Banks 2014, p. 11.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 2, para 2.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 2, para 3.

- Banks 2014, p. 12.

- Banks 2014, p. 13.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 2, para 4.

- Banks 2014, p. 17.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 5, para 22.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 5, para 23.

- Banks 2014, p. 20.

- Banks 2014, pp. 21–22.

- The Guardian 4 January 1967.

- The Guardian 3 August 1966.

- Banks 2014, pp. 16–17.

- Banks 2014, pp. 29–31.

- Board of Trade report 1967, pp. 5–6, para 24.

- Banks 2014, p. 22.

- Board of Trade report 1967, pp. 4–5, para 16.

- Banks 2014, p. 37.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 3, para 6.

- Banks 2014, p. 18.

- Banks 2014, p. 41.

- Banks 2014, pp. 39–40.

- Board of Trade report 1967, pp. 3–4, para 10.

- Banks 2014, p. 43.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 3, para 9.

- Banks 2014, p. 47.

- Banks 2014, pp. 49–50.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 6, para 25.

- Banks 2014, p. 56.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 6, para 30.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 6, para 31.

- Banks 2014, p. 57.

- Banks 2014, p. 59.

- Banks 2014, p. 62.

- Banks 2014, pp. 60–61.

- Commons debate 3 August 1966, cc486–90.

- The Guardian 4 August 1966.

- Board of Trade report 1967, pp. 6–7, paras 32–33.

- Banks 2014, pp. 64–65.

- Commons debate 2 August 1966, cc255–58.

- Commons debate 3 August 1966, cc486–90.

- Banks 2014, pp. 74–75.

- Remembering the Darlwyne disaster 2016.

- Banks 2014, p. 76.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 4, para 13.

- The Guardian 19 December 1966.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 4, para 14.

- Banks 2014, p. 51.

- Banks 2014, p. 82.

- The Guardian 21 December 1966.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 1.

- The Guardian 13 December 1966.

- The Guardian 14 March 1967.

- The Guardian 22 December 1966.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 7, para 35.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 4, para 15.

- Banks 2014, p. 89.

- Board of Trade report 1967, pp. 3–4, paras 10–11.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 5, para 21.

- The Guardian 6 January 1967.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 7, para 39.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 7, para 34.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 6, para 29.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 7, paras 37–38.

- Banks 2014, p. 91.

- Banks 2014, pp. 92–95.

- Banks 2014, pp. 96–97.

- Board of Trade report 1967, p. 7, para 40.

- Commons debate 15 March 1967, cc480–81.

- Divernet November 2016.

- The Daily Mirror 31 July 2016.

- Cornwall shipwreck Darlwyne 'discovered' 31 July 2016.

- BBC 31 July 2016.

- The Telegraph 31 July 2016.

- Banks 2014, pp. 17, 32–33, 35.

Sources

Books, newspapers, journals

- Banks, Martin (2014). The Mysterious Loss of the Darlwyne. Exeter: Tamar Books. ISBN 978-0-9574742-1-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Cornwall shipwreck Darlwyne 'discovered' 50 years after maritime disaster claimed 31 lives". The Independent. 31 July 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- "Darlwin 'in poor condition'". The Guardian. 3 August 1966. p. 1. ProQuest 185168159. (subscription required)

- "Relatives charter planes to search for the Darlwin". The Guardian. 4 August 1966. p. 14. ProQuest 185167770. (subscription required)

- "Darlwin posters seized". The Guardian. 7 August 1966. p. 3. ProQuest 475844016. (subscription required)

- "Darlwyne inquiry today". The Guardian. 13 December 1966. p. 14. ProQuest 185134558. (subscription required)

- "Darlwyne 'carried down' her victims". The Guardian. 19 December 1966. p. 4. ProQuest 185186723. (subscription required)

- "No special check made on unlicensed boats after Darlwyne disaster". The Guardian. 21 December 1966. p. 4. ProQuest 185214822. (subscription required)

- "Man denies fixing trip on Darlwyne". The Guardian. 22 December 1966. p. 4. ProQuest 185141867. (subscription required)

- "'No one told' of Darlwyne sale". The Guardian. 4 January 1967. p. 5. ProQuest 185070805. (subscription required)

- "Conflicts over telephone alert for Darlwyne". The Guardian. 6 January 1967. p. 11. ProQuest 185221734. (subscription required)

- "Inquiry finds that Darlwyne was 'not fit for sea'". The Guardian. 14 March 1967. p. 5. ProQuest 185233355. (subscription required)

- "Darlwyne mystery 'solved' exactly 50 years on as divers find wreck of tourist boat that disappeared in storm". The Telegraph. 31 July 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- "Mystery of long lost ship which sank killing 31 day after England won World Cup finally 'solved'". The Daily Mirror. 31 July 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

Online

- "Darlwyne — the forgotten tragedy of 1966". Diver magazine online. November 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "Lost Cornish shipwreck Darlwyne 'found' after 50 years". BBC News. 31 July 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- "Pleasure Boat Darlwin". Hansard. 733. 2 August 1966. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- "Pleasure Boat Darlwin". Hansard. 733. 3 August 1966. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- "Pleasure Boats (Licensing)". Hansard. 743. 15 March 1967. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Remembering the Darlwyne disaster 50 years on". this is the west country.co.uk. Newsquest Media. 26 July 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- "The Merchant Shipping Act 1894. Report of Court No. 8042: MV Darlwyne" (PDF). Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 13 January 1967. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)