Long Spur (conservation area)

Long Spur is a wildland in the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests of western Virginia. The Wilderness Society has designated the area as a "Mountain Treasure," as a special place worthy of protection from logging and road construction.[1]

| Long Spur | |

|---|---|

Location of the Long Spur wildarea in Virginia | |

| Location | Bland County Virginia, United States |

| Nearest town | Bland, Virginia |

| Coordinates | 37°3′58″N 81°2′57″W |

| Area | 6,413 acres (25.95 km2) |

| Administrator | U.S. Forest Service |

Trails in the area include an old section of the Appalachian Trail and a trail that follows a native trout stream, Spur Branch. A good view of the area is obtained from High Rock, just outside the area on the northeastern boundary.[1]

The area is part of the Walker Mountain Cluster.

Location and access

_at_U.S._Route_52_and_Virginia_State_Route_42_in_Bland%2C_Bland_County%2C_Virginia.jpg)

The area is located in the Appalachian Mountains of Southwestern Virginia, east of Interstate 77 and about 3 miles southeast of Bland, Virginia.[2]

The only trails in the area are an old section of the Appalachian Trail and a foot trail along Spur Branch that goes from VA 602 to the former Appalachian Trail. While these trails are not official trails, they are kept open by hikers and hunters.[3]

Road access to the area is from VA 602 (Spur Branch Road) on the north side, and VA 601 (Little Creek Road) on the south. VA 602 continues past Spur Branch to the viewpoint at High Rock.[4][2]

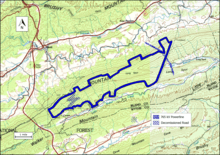

The boundary of the wildland as determined by the Wilderness Society is shown in the adjacent map.[1] Additional roads and trails are given on National Geographic Maps 787 (Blacksburg, New River Valley, Trails Illustrated Hiking Maps, 787).[2] A great variety of information, including topographic maps, aerial views, satellite data and weather information, is obtained by selecting the link with the wild land's coordinates in the upper right of this page.

Additional access can be gained using old logging roads. The Appalachian Mountains were extensively timbered in the early twentieth century, leaving logging roads that are becoming overgrown but still passable.[5] Old logging roads and railroad grades can be located by consulting the historical topographic maps available from the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The Long Spur wildarea is covered by USGS topographic maps Bland and Long Spur.[1]

Natural history

The area is part of the Central Appalachian Broadleaf Coniferous Forest-Meadow Province. Yellow poplar, northern red oak, white oak, basswood, cucumber tree, white ash, eastern hemlock and red maple are found in colluvial drainages, toeslopes and along flood plains of small to medium-sized streams. White oak, northern red oak, and hickory dominate on the north and west, while chestnut oak, scarlet oak and yellow pine are found on ridgetops and exposed sites.[4] Wildlife populations are supported by five artificial waterholes created by blasting into rock.[4] Glades with box huckleberry, an unusual biological community, are found here.[3] There is a wild trout population in Spur Branch.[4]

A wide variety of ecological types has been created by many cuts in the area’s topography, including hot, dry windswept ridges; cool, moist protected coves; and rich bottomlands.[4] There are large tracts of old-growth forest in the area, with some stands on the western side at least 140 years old.[3]

Topography

The wildland is part of the Ridge and Valley Subsection of the Northern Ridge and Valley Ecosystem Section. Ridges composed of sandstone and shale run northeast/southwest, with parallel valleys created from limestone or shale. Big Walker Mountain and Long Spur, the principal mountains in the area, have both steep and gentle slopes. Gentle slopes are found along Little Walker Creek, a stream that runs parallel to VA 601 along the southern border. There are many tribuitaries flowing into Little Walker Creek; Spur Branch is a prominent drainage in the northeast that flows into Little Walker Creek.[4]

Water levels in Little Walker Creek in winter and early spring are sufficient for canoeing on an average of 16-18 days of the year. The creek, about 30 feet in width, moves through a pastoral valley with farmland and occasional ridges rising steeply from the creek, giving a sense of being far removed from the civilized world. However care must be taken after the creek passes under the Route 100 bridge where it begins to flow through a boulder-filled gorge.[6]

The lowest elevation of 2080 feet is found near Little Walker Creek, and the high elevation of 3120 feet is found at a point on the crest of Long Spur.[4]

Forest Service management

The Forest Service has conducted a survey of their lands to determine the potential for wilderness designation. Wilderness designation provides a high degree of protection from development. The areas that were found suitable are referred to as inventoried roadless areas. Later a Roadless Rule was adopted that limited road construction in these areas. The rule provided some degree of protection by reducing the negative environmental impact of road construction and thus promoting the conservation of roadless areas.[1] Long Spur was inventoried in the roadless area review, and therefore protected from possible road construction and timber sales.[3]

The area is divided by a 765 kilovolt power line constructed by the Appalachian Electric Power Company in 2003. The smaller section, near High Rock, includes old growth forest and lands within the "Indiana Bat Primary" habitat prescription.[3]

The forest service classifies areas under their management by a recreational opportunity setting that informs visitors of the diverse range of opportunities available in the forest.[7] A large part of the area is designated "Remote Backcountry-Non-motorized. A section on the south near Little Walker Creek is designated "Mix of Successional Habitats" and "Old Growth with Disturbance".[3]

Cultural history

While no prehistoric and historic sites were found in a 247-acre survey, the area is considered of moderate potential for such resources.[4]

See also

References

- Parsons, Shireen (May 1999). Virginia's Mountain Treasures, The Unprotected Wildlands of the Jefferson National Forest. Washington, D. C.: The Wilderness Society, OCLC: 42806366. p. 50.

- Trails Illustrated Maps (2011). Blacksburg, New River Valley (Trails Illustrated Hiking Maps, 787). Washington, D. C.: National Geographic Society.

- Bamford, Sherman (February 2013). A Review of the Virginia Mountain Treasures of the Jefferson National Forest. Blacksburg, Virginia: Sierra Club, OCLC: 893635467. p. 49.

- Revised Land and Resource Management Plan for the Jefferson National Forest, Management Bulletin R8-MB 115E. Roanoke, Virginia: Jefferson National Forest, US Department of Agriculture. 2004. pp. C-111–C-118.

- Sarvis, Will (2011). The Jefferson National Forest. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 1-57233-828-8.

- Corbett, Roger (1988). Virginia Whitewater. Rockville, Maryland: Seneca Press. p. 448.

- "Recreation Opportunity Setting as a Management Tool" (PDF).

Further reading

- Stephenson, Steven L., A Natural History of the Central Appalachians, 2013, West Virginia University Press, West Virginia, ISBN 978-1933202-68-6.

- Davis, Donald Edward, Where There Are Mountains, An Environmental History of the Southern Appalachians, 2000, University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia. ISBN 0-8203-2125-7.