London Necropolis Railway

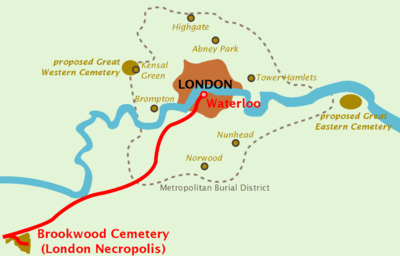

The London Necropolis Railway was a railway line opened in November 1854 by the London Necropolis Company (LNC), to carry corpses and mourners between London and the LNC's newly opened Brookwood Cemetery 23 miles (37 km) southwest of London in Brookwood, Surrey. At the time the largest cemetery in the world, Brookwood Cemetery was designed to be large enough to accommodate all the deaths in London for centuries to come, and the LNC hoped to gain a monopoly on London's burial industry. The cemetery had intentionally been built far enough from London so as never to be affected by urban growth and was dependent on the recently invented railway to connect it to the city.

| London Necropolis Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Funeral train | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Branches into the termini at both ends defunct; most of the route still in use as part of the South West Main Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | London and Surrey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | London Necropolis railway station Brookwood Cemetery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 3 dedicated stations; other stations on the London and South Western Railway also served occasionally | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 13 November 1854 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | 11 April 1941 (last day of service; official closure May 1941) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | The London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company (renamed London Necropolis Company after 1927) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 24 mi (39 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The railway mostly ran along the existing tracks of the London and South Western Railway (LSWR) but had its own branches from the main line at both London and Brookwood. Trains carried coffins and passengers from a dedicated station in Waterloo, London, onto the LSWR tracks. On reaching the cemetery, the trains reversed down a dedicated branch line to two stations in the cemetery, one for the burial of Anglicans and one for Nonconformists (non-Anglicans) or those who did not want a Church of England funeral. The station waiting rooms and the compartments of the train, both for living and for dead passengers, were partitioned by both religion and class to prevent both mourners and cadavers from different social backgrounds from mixing. As well as the regular funeral traffic, the London Necropolis Railway was used to transport large numbers of exhumed bodies during the mass removal of a number of London graveyards to Brookwood.

The company failed to gain a monopoly of the burial industry, and the scheme was not as successful as its promoters had hoped. While they had planned to carry between 10,000 and 50,000 bodies per year, in 1941 after 87 years of operation, only slightly over 200,000 burials had been conducted in Brookwood Cemetery, equalling roughly 2,300 bodies per year.

On the night of 16–17 April 1941, the London terminus was badly damaged in an air raid and rendered unusable. Although the LNC continued to operate occasional funeral services from Waterloo station to Brookwood railway station immediately north of the cemetery, the London Necropolis Railway was never used again. Soon after the end of the Second World War the surviving parts of the London station were sold as office space, and the rail tracks in the cemetery were removed. The part of the London building which housed the LNC's offices survives today. The two stations in the cemetery remained open as refreshment kiosks for some years afterwards but were subsequently demolished. The site of the northern station, serving the Nonconformist cemetery, is now heavily overgrown. The site of the southern, Anglican, station is now the location of a Russian Orthodox monastery and a shrine to King Edward the Martyr, which incorporate the surviving station platform and the former station chapels.

London burial crisis

London's dead had traditionally been buried in and around local churches,[1] and with a limited amount of space for burials, the oldest graves were regularly exhumed to free space for new burials.[2] In the first half of the 19th century the population of London more than doubled, from a little under a million people in 1801 to almost two and a half million in 1851.[3] Despite this rapid growth in population, the amount of land set aside for use as graveyards remained unchanged at approximately 300 acres (0.5 sq mi; 1.2 km2),[3] spread across around 200 small sites.[4] Graveyards became very congested.[5] Decaying corpses contaminated the water supply and the city suffered regular epidemics of cholera, smallpox, measles and typhoid.[6] Public health policy at this time was generally shaped by the miasma theory (the belief that airborne particles were the primary factor in the spread of contagious disease), and the bad smells and risks of disease caused by piled bodies and exhumed rotting corpses caused great public concern.[7] A Royal Commission established in 1842 to investigate the problem concluded that London's burial grounds had become so overcrowded that it was impossible to dig a new grave without cutting through an existing one.[8]

In 1848–49 a cholera epidemic killed 14,601 people in London and overwhelmed the burial system completely.[9] Bodies were left stacked in heaps awaiting burial, and even relatively recent graves were exhumed to make way for new burials.[10][11]

Proposed solutions

In the wake of public concerns following the cholera epidemics and the findings of the Royal Commission, the Act to Amend the Laws Concerning the Burial of the Dead in the Metropolis (Burials Act) was passed in 1851. Under the Burials Act, new burials were prohibited in what were then the built-up areas of London.[12] Seven large cemeteries had recently opened a short distance from the centre of London or were in the process of opening, and temporarily became London's main burial grounds.[13] The government sought a means to prevent the constantly increasing number of deaths in London from overwhelming the new cemeteries in the same manner in which it had overwhelmed the traditional burial grounds.[14] Edwin Chadwick proposed the closure of all existing burial grounds in the vicinity of London other than the privately owned Kensal Green Cemetery northwest of the city, which was to be nationalised and greatly enlarged to provide a single burial ground for west London. A large tract of land on the Thames around 9 miles (14 km) southeast of London in Abbey Wood was to become a single burial ground for east London.[3] The Treasury was sceptical that Chadwick's scheme would ever be financially viable, and it was widely unpopular.[14][15] Although the Metropolitan Interments Act 1850 authorised the scheme, it was abandoned in 1852.[15]

London Necropolis Company

An alternative proposal was drawn up by Sir Richard Broun and Richard Sprye, who planned to use the emerging technology of mechanised transport to resolve the crisis.[15] The scheme entailed buying a single very large tract of land around 23 miles (37 km) from London in Brookwood near Woking, Surrey, to be called Brookwood Cemetery or the London Necropolis.[16][note 1] At this distance, the land would be far beyond the maximum projected size of the city's growth.[18] The London and South Western Railway (LSWR)—which had connected London to Woking in 1838—would enable bodies and mourners to be shipped from London to the site easily and cheaply.[15] Broun envisaged dedicated coffin trains, each carrying 50–60 bodies, travelling from London to the new Necropolis in the early morning or late at night, and the coffins being stored on the cemetery site until the time of the funeral.[19] Mourners would then be carried to the appropriate part of the cemetery by a dedicated passenger train during the day.[20]

Broun calculated that a 1,500-acre (2.3 sq mi; 6.1 km2) site would accommodate a total of 5,830,500 individual graves in a single layer.[15] If the practice of only burying a single family in each grave were abandoned and the traditional practice for pauper burials of ten burials per grave were adopted, the site was capable of accommodating 28,500,000 bodies.[15] Assuming 50,000 deaths per year and presuming that families would often choose to share a grave, Broun calculated that even with the prohibition of mass graves it would take over 350 years to fill a single layer of the cemetery.[21] Although the Brookwood site was a long distance from London, Broun and Sprye argued that the speed of the railway made it both quicker and cheaper to reach than the seven existing cemeteries, all of which required a slow and expensive horse-drawn hearse to carry the body and mourners from London to the burial site.[21]

Shareholders in the LSWR were concerned at the impact the cemetery scheme would have on the normal operations of the railway. At a shareholders' meeting in August 1852 concerns were raised about the impact of funeral trains on normal traffic and of the secrecy in which negotiations between the LSWR and the promoters of the cemetery were conducted.[17] The LSWR management pledged that no concessions would be made to the cemetery operators, other than promising them the use of one train each day.[17] Charles Blomfield, Bishop of London was hostile in general to railway funeral schemes, arguing that the noise and speed of the railways was incompatible with the solemnity of the Christian burial service. Blomfield also considered it inappropriate that the families of people from very different backgrounds would potentially have to share a train, and felt that it demeaned the dignity of the deceased for the bodies of respectable members of the community to be carried on a train also carrying the bodies and relatives of those who had led immoral lives.[22][23][note 2]

On 30 June 1852 the promoters of the Brookwood scheme were given Parliamentary consent to proceed, and the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company (LNC) was formed.[24] The former Woking Common near Brookwood, owned by the Earl of Onslow, was chosen as the site for the new cemetery.[25] To prevent the LSWR from exploiting its monopoly on access to the cemetery, the private Act of Parliament authorising the scheme bound the LSWR to carry corpses and mourners to the cemetery in perpetuity and set a maximum tariff which could be levied on funeral traffic, but did not specify detail of how the funeral trains were to operate.[26]

Broun's scheme had envisaged the cemetery running along both sides of the LSWR main line and divided by religion, with separate private railway halts on the main line, each incorporating a chapel, to serve each religion's section.[27] The new consulting engineer to the company, William Cubitt, rejected this idea and recommended a single site to the south of the railway line, served by a private branch line through the cemetery.[28] The company also considered Broun's plan for dedicated coffin trains unrealistic, arguing that relatives would not want the coffins to be shipped separately from the deceased's family.[29]

Internal disputes within the LNC led to Broun and Sprye losing control of the scheme,[26] and later delays and allegations of mismanagement caused further changes to the scheme's management.[24][25] In September 1853 under a new board of trustees work began on the scheme.[25] A site for the London rail terminus was identified and leased,[30] and a 2,200-acre (3.4 sq mi; 8.9 km2) tract of land stretching from Woking to Brookwood was purchased from Lord Onslow.[27][30] The westernmost 400 acres (0.62 sq mi; 1.6 km2), at the Brookwood end, were designated the initial cemetery site,[27] and a branch railway line was built from the main line into this section.[25][note 3] On 7 November 1854 the new cemetery opened and the southern Anglican section was consecrated by Charles Sumner, Bishop of Winchester.[31][note 4] At the time it was the largest cemetery in the world.[33] On 13 November the first scheduled train left the new London Necropolis railway station for the cemetery, and the first burial (that of the stillborn twins of a Mr and Mrs Hore of Ewer Street, Borough) took place.[34][note 5]

Cemetery railway branch

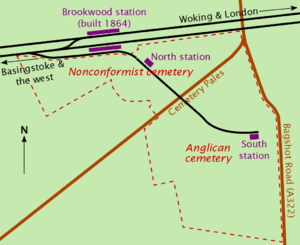

William Cubitt decided that the terrain of the initial cemetery site was best suited to a railway branch at the west of the cemetery. Work began on the earthworks and rails for the new branch in early September 1854.[28] The single-track branch was completed in time for the opening two months later, at a total construction cost of £1419 17s 6d (about £128,000 in terms of 2020 consumer spending power).[28][37] The junction with the LSWR, known as Necropolis Junction, was west-facing, meaning that trains to and from London were obliged to reverse in and out of the branch.[28] No run-around loop was provided at Necropolis Junction, and a single crossover allowed trains from the Necropolis branch to reverse onto the northern (London-bound) track of the LSWR.[28]

The new branch ran east from Necropolis Junction on a downhill gradient. After passing through white gates marking the boundary of the cemetery, it curved south into the northern, Nonconformist section of the cemetery, the site of North station (51.30281°N 0.63264°W).[38] The line straightened and ran southeast over a level crossing across Cemetery Pales, the road dividing the northern and southern halves of the initial cemetery site.[38] After crossing Cemetery Pales the branch turned east and ran through the southern, Anglican, section of the cemetery, terminating at South station (51.29977°N 0.62300°W) near the road from Bagshot to Guildford (today the A322) which marked the eastern boundary of the site.[38] Along with the major roads and paths in the cemetery, the entire branch was lined with giant sequoia trees, the first significant planting of these trees (only introduced to Europe in 1853) in Britain.[39] Aside from a short 100-yard (91 m) siding just south of Cemetery Pales, built in 1904–05 to serve the LNC's new masonry workshop, the layout of the branch remained unchanged throughout its operation.[38][40] In 1914 a brick water tower was added near the masonry works siding, to allow the LNC's locomotives to refill their tanks before returning to London and thus avoid the need to interrupt their journey to refill at Woking.[41]

The poor quality gravel soil, which had been the initial reason for the site's cheapness and its selection as the site for the cemetery, was poorly suited as a railway trackbed. The LNC's rails, and in particular its sleepers, deteriorated rapidly and needed constantly to be replaced.[42]

In the early years of the cemetery's operation, the locomotives hauling the funeral trains from Waterloo would not travel down the branch into the cemetery, as it would leave the engine at the wrong end of the train for the return journey.[43] Instead, the train would stop immediately after passing Necropolis Junction, and the carriages would be uncoupled from the engine. A team of black horses would then haul the carriages down the sloping branch line to the two cemetery stations. While the train was on the branch line the engine would be repositioned so as to be at the front of the train once the horses drew it back out of the branch and onto the main line.[43]

In 1864 Brookwood (Necropolis) railway station on the LSWR opened,[28] immediately east of Necropolis Junction.[44] In conjunction with the building of the station a run-around loop was added at Necropolis Junction, allowing locomotives to reposition themselves from the front to the rear of the train. From then on, on arrival at Necropolis Junction from London the engine would not be repositioned, but would push the train into the cemetery from the rear, under the close supervision of LNC staff. This left the engine positioned to pull the train out of the cemetery, after which it would use the run-around loop to move to the other end of the train and pull it back to London.[45] Between 1898 and 1904 the LSWR line through Brookwood was increased from two to four tracks; a thin slice of the northernmost part of the cemetery was ceded to the LSWR to allow the widening of the line.[28] Brookwood station was rebuilt, and a new junction to the west of the station allowed trains to pass between the cemetery branch and all four of the LSWR lines.[38]

Operations

The London Necropolis Company offered three classes of funerals, which also determined the type of railway ticket sold to mourners and the deceased. A first class funeral allowed the person buying the funeral to select the grave site of their choice anywhere in the cemetery;[note 6] at the time of opening prices began at £2 10s (about £236 in 2020 terms) for a basic 9-by-4-foot (2.7 m × 1.2 m) plot with no special coffin specifications.[37][46] It was expected by the LNC that those using first class graves would erect a permanent memorial of some kind in due course following the funeral. Second class funerals cost £1 (about £95 in 2020 terms) and allowed some control over the burial location.[29] The right to erect a permanent memorial cost an additional 10 shillings (about £47 in 2020 terms); if a permanent memorial was not erected the LNC reserved the right to re-use the grave in future.[37][46] Third class funerals were reserved for pauper funerals; those buried at parish expense in the section of the cemetery designated for that parish. Although the LNC was forbidden from using mass graves (other than the burial of next of kin in the same grave) and thus even the lowest class of funeral provided a separate grave for the deceased, third class funerals were not granted the right to erect a permanent memorial on the site.[29] (The families of those buried could pay afterwards to upgrade a third-class grave to a higher class if they later wanted to erect a memorial, but this practice was rare.)[47]

At the time the service was inaugurated, the LNC's trains were divided both by class and by religion, with separate Anglican and Nonconformist sections and separate first, second and third class compartments within each.[48] This separation applied to both living and dead passengers. This was to prevent persons from different social background from mixing and potentially distressing mourners and to prevent bodies of persons from different social classes being carried in the same compartment, rather than to provide different levels of facilities for different types of mourner; the compartments intended for all classes and religions were very similar in design, and the primary difference was different ornamentation on the compartment doors.[19] At 11.35 am (11.20 am on Sundays) the train would leave London for Brookwood, arriving at Necropolis Junction at 12.25 pm (12.20 pm on Sundays).[49][note 7]

The LNC's trains were capable of transporting large numbers of mourners when required; the funeral of businessman Sir Nowroji Saklatwala on 25 July 1938 saw 155 mourners travelling first class on a dedicated LNC train.[50] For extremely large funerals such as those of major public figures, the LSWR would provide additional trains from Waterloo to Brookwood station on the main line to meet the demand.[51] Charles Bradlaugh, Member of Parliament for Northampton, was a vocal advocate of Indian self-government and a popular figure among the Indian community in London, many of whom attended his funeral on 3 February 1891.[52] Over 5,000 mourners were carried on three long special LSWR trains, one of which was 17 carriages long.[51] The mourners included the 21-year-old Mohandas Gandhi, who recollected witnessing a loud argument between "a champion atheist" and a clergyman at North station while waiting for the return train.[52]

The return trains to London generally left South station at 2.15 pm and Necropolis Junction at 2.30 pm; the return journey initially took around an hour owing to the need to stop to refill the engine with water, but following the construction of the water tower in the cemetery this fell to around 40 minutes.[53] An 1854 agreement between the LNC and LSWR gave consent for the LNC to operate two or three funeral trains each day if demand warranted it, but traffic levels never rose to a sufficient level to activate this clause.[54]

The train only ran if there was a coffin or passengers at the London terminus waiting to use it, and both the journey from London to Brookwood and the later return would be cancelled if nobody was due to leave London that morning.[48] It would not run if there was only a single third or second class coffin to be carried, and in these cases the coffin and funeral party would be held until the next service.[55] Generally the trains ran direct from London to the cemetery, other than occasional stops to take on water. Between 1890 and 1910 the trains also sometimes stopped at Vauxhall and Clapham Junction for the benefit of mourners from south west London who did not want to travel via Waterloo, but these intermediate stops were discontinued and never reinstated.[54] After 1 October 1900 the Sunday trains were discontinued, and from 1902 the daily train service was ended and trains ran only as required.[56]

Fares

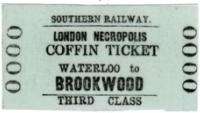

The Act of Parliament establishing the LNC had specified maximum ticket prices for the railway, and traffic never rose to the level at which it would have been justified for either the LNC or the LSWR to undertake costly and time-consuming lobbying for a change in the legislation. As a consequence, despite the effects of inflation, competition and variable costs the fares of the London Necropolis Railway never changed throughout the first 85 of its 87 years of operation.[58] Live passengers were charged 6s in first class, 3s 6d in second class and 2s in third class (in 1854 worth about £28, £17 and £9 respectively in 2020 consumer terms) for a return ticket, while dead passengers were charged £1 in first class, 5s in second class and 2s 6d in third class (in 1854 worth about £95, £24 and £12 respectively in 2020 consumer terms) for a one-way ticket.[37][59] As the railway was intended only to be used by Londoners visiting the cemetery or attending funerals, the only tickets ever issued to living passengers were returns from London.[60] In 1918 the LSWR (which provided the LNC's passenger carriages) abandoned second class services and the LNC as a consequence discontinued the sale of second class fares to living passengers, but continued to separate coffin tickets into first, second and third class dependent on the type of funeral booked.[61]

Intentionally set at a low level at the time the cemetery and railway opened, in later years the fixed fares offered a very substantial saving over main line tickets to Brookwood (in 1902 the 4s LSWR third class fare to Brookwood was twice the cost of the LNC's equivalent). Additional LNC traffic was generated by golfers disguised as mourners travelling to the golf course which had been built on those parts of the land bought by the LNC in 1852 which had not yet been incorporated into the cemetery.[23][62] The fixed fares prompted complaints from other London funeral firms after the opening of Woking Crematorium in 1885, as rival undertakers were not given access to the LNC's cheap trains and had to pay the LSWR's cargo rate (24 shillings in 1885) to ship a coffin to Brookwood or Woking stations for transfer to the crematorium.[63][note 8]

In its last two years of operation, wartime rises in costs made the fixed fare structure untenable, and between July 1939 and January 1941 there were five slight adjustments to the fares. The live passenger rates rose to 7s 5d in first class and 2s 6d in third class, with equivalent changes to the fares for coffins. These fares remained far cheaper than the equivalent fares from Waterloo to Brookwood for both living and dead passengers on the Southern Railway (SR), which had absorbed the LSWR in the 1923 restructuring of Britain's railways.[66] The fare structure of January 1941 remained in use following the April 1941 suspension of London Necropolis Railway services, for the occasional funerals conducted by the LNC using the SR's platforms at Waterloo station, but the SR only allowed mourners attending funerals to use these cheap fares and not those visiting the cemetery.[67]

Relocation of London burial grounds

I did it wholesale and had 220 very large cases made each containing 26 human bodies besides children and these weighed 43⁄4 cwt. There were 1,035 cwt of human remains sent in these cases alone. They were conveyed in the night and the Cemetery Company made arrangements for them. Each body has cost us less than three shillings. It was fortunate that such reasonable terms could be made at Woking Cemetery. A more horrible business you can scarcely imagine; the men could only continue their work by the constant sprinkling of disinfectant powder. Mine was no easy task for the Bishop, the Warden, the parishioners and particularly the relatives have watched the steps taken, and the interviews with people and the correspondence has been great but all are more satisfied than could be expected.

— Architect Edward Habershon on the relocation of Cure's College burial ground, October 1862.[68]

As well as taking over new burials from London's now-closed burial grounds, the LNC also envisaged the physical relocation of the existing burial grounds to their Necropolis, to provide a final solution to the problems caused by burials in built-up areas.[36] The massive London civil engineering projects of the mid-19th century—the railways, the sewer system and from the 1860s the precursors to the London Underground—often necessitated the demolition of existing churchyards.[69] The first major relocation took place in 1862, when the construction of Charing Cross railway station and the railway lines into it necessitated the demolition of the burial ground of Cure's College in Southwark.[69] Around 5,000 cubic yards (3,800 m3) of earth was displaced, uncovering at least 7,950 bodies.[69] These were packed into 220 large containers, each containing 26 adults plus children, and shipped on the London Necropolis Railway to Brookwood for reburial, along with at least some of the existing headstones from the cemetery, at a cost of around 3 shillings per body.[36] At least 21 London burial grounds were relocated to Brookwood via the railway, along with numerous others relocated by road following the railway's closure.[36]

Brookwood American Cemetery and Memorial

In 1929 a section of the LNC's land at Brookwood was set aside as Brookwood American Cemetery and Memorial, the sole burial ground in Britain for US military casualties of the First World War.[70] As most US casualties had occurred in continental Europe and been buried there the number interred at Brookwood was small,[71] with a total of 468 servicemen buried in the cemetery.[72] After the entry of the United States into the Second World War the American cemetery was enlarged, with burials of US servicemen beginning in April 1942. With large numbers of American personnel based in the west of England, a dedicated rail service for the transport of bodies operated from Devonport to Brookwood. By August 1944 over 3,600 bodies had been buried in the American Military Cemetery. At this time burials were discontinued, and US casualties were from then on buried at Cambridge American Cemetery and Memorial.[71]

On the authority of Thomas B. Larkin, Quartermaster General of the United States Army, the US servicemen buried at Brookwood during the Second World War were exhumed in January–May 1948.[73] Those whose next of kin requested it were shipped to the United States for reburial,[73] and the remaining bodies were transferred to the new cemetery outside Cambridge.[71] (Brookwood American Cemetery had also been the burial site for those US servicemen executed while serving in the United Kingdom, whose bodies had been carried to Brookwood by rail from the American execution facilities at Shepton Mallet. They were not transferred to Cambridge in 1948, but instead reburied in unmarked graves at Oise-Aisne American Cemetery Plot E, a dedicated site for US servicemen executed during the Second World War.)[71][note 9] The railway service had been suspended in 1941, and North station (renamed North Bar after the ending of rail services[32]) was used as a temporary mortuary to hold these bodies while awaiting shipment to the USA or Cambridge.[73] As the branch line into the cemetery was no longer in use, temporary platforms were built on the branch line serving the National Rifle Association's shooting range at Bisley, on the opposite side of the LSWR line from the cemetery.[71] Following the removal of the US war graves the site in which they had been buried was divided into cemeteries for the Free French forces and Italian prisoners of war.[71]

Rolling stock

Locomotives

_(geograph-1679880).jpg)

Under the terms of the 1852 agreement and Act of Parliament establishing the London Necropolis Company, the LSWR (after 1923 the SR) provided the locomotives and crew for London Necropolis Railway operations.[74] There was no dedicated LNC locomotive, and the trains were worked by whichever suitable engine happened to be available.[74] (Before the 1864 improvements to Necropolis Junction, locomotives rarely entered the cemetery branch line itself and the trains were generally hauled along the branch line by horses.[43]) Towards the end of the railway's operations in the 1930s the route was almost always worked by LSWR M7 class locomotives, usually No. 255.[74]

Passenger carriages

The passenger carriages used on the London Necropolis Railway were not owned by the LNC, but loaned from the LSWR. A set of carriages was permanently loaned, rather than carriages being lent as needed, as the LSWR was concerned that passengers might be discouraged from using regular LSWR services if they knew that their carriages had potentially carried dead bodies recently.[75]

The original set of carriages, used between 1854 and 1899, were four-wheeled carriages to a design by Joseph Hamilton Beattie. Little is recorded about the number and specifications of the carriages. The same set of carriages remained in use for over 40 years, prompting increasingly strong complaints from the LNC about their deteriorating quality.[76]

As part of an 1896 agreement by which the LSWR re-equipped the LNC in conjunction with the repositioning of the LNC's London terminus, the LNC demanded that the new passenger carriages to be supplied by the LSWR be "of a quality and a character not inferior to [the LSWR's] ordinary main line traffic".[76] These new carriages were supplied late in the 19th century, probably in December 1899.[76] They were all six-wheeled, and comprised two 30-foot (9.1 m) passenger brake vans each containing three third class compartments, a baggage compartment and the guard's compartment; a 34-foot (10 m) passenger carriage divided into three first class and two second class compartments; and a 30-foot (9.1 m) passenger carriage divided into five third class compartments (also used as all second class).[76] Although not recorded, it is likely that other carriages were also permanently loaned to the LNC for use as needed.[77]

This set of carriages only remained in use for a short period, and in 1907 was replaced by a new set of carriages of which little is known.[77] In 1917 this set was itself replaced by two 51-foot (16 m) passenger brake vans each containing two first and four third class compartments, a 50-foot (15 m) carriage with three first and three third class compartments, and a 46-foot (14 m) carriage with six third class compartments.[78]

This set operated for most of the inter-war period, being withdrawn in April 1938. It was replaced by a very similar set of coaches at this time, which was withdrawn in September 1939 after the outbreak of hostilities for use in troop trains.[79] The carriages were replaced by the former Royal Train, built 1900–04, of the now-defunct South Eastern and Chatham Railway.[80] These ornately decorated carriages were those destroyed in the 1941 bombing of the London terminus.[80]

Hearse vans

Unlike the loaned locomotives and passenger carriages, the LNC owned its dedicated hearse vans outright.[19] Despite this, they were always painted in whichever colour scheme was currently in use by the LSWR (SR after 1923), to match the livery of the passenger cars and locomotives loaned to the LNC.[81]

As with the carriages for living passengers, the hearse vans were designed to prevent bodies mixing with those from different backgrounds.[19] Each of the original vans was partitioned into twelve sections in two rows of six, each capable of holding one coffin;[82] later vans were of a slightly different design and probably carried 14 coffins.[81] The vans were fitted with internal partitions to divide first, second and third class coffins.[82] The LNC intended to use half the hearse vans for Anglican and half for Nonconformist coffins, to prevent Anglicans from sharing a carriage with Nonconformists, but in practice this arrangement was little used.[82] Unlike traditional Victorian funerals, in which the hearse invariably led the funeral procession, photographic evidence shows that the LNC sometimes placed the hearse van at the rear of the train.[82] (Because trains reversed from Necropolis Junction into the cemetery, no matter which arrangement was used the hearse van would inevitably be at the rear of the train for part of the journey.)

The LNC ordered six hearse vans in 1854, two of which were operational at the time the cemetery and Necropolis Railway opened.[82] Their origins are not recorded, although they were bought very cheaply suggesting that they were conversions of existing carriages rather than built to order.[83] Many LNC records from this period have been lost and it is not certain how many hearse vans were delivered, and how they were used; records suggest that anything between three and ten hearse vans were bought or leased by the LNC in the early years of operations.[84] (As each van carried 12–14 coffins and it is known that some funeral trains in the late 19th century carried over 60 coffins, at least six hearse vans must have been in use.)[84]

As part of the settlement during the relocation of the London terminus, two new hearse vans were given to the LNC by the LSWR in 1899.[81] These new hearse vans were longer, and divided into three levels with compartments for eight coffins on each, for a total of 24 coffins per van.[75] These replaced the existing hearse vans and remained in use until the closure of the Necropolis Railway.[75] One of the vans was destroyed in the 1941 bombing of the London terminus; the other was transferred to the SR and remained in use until at least 1950.[75] The former Royal Train brought into passenger service on the London Necropolis Railway in 1939 had a large amount of luggage space, and it is probable that when funeral traffic was light the hearse vans were not used and the coffins carried in the luggage space.[80]

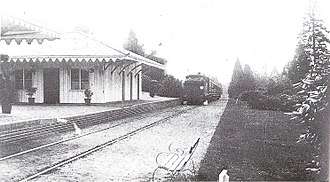

Cemetery stations

On William Cubitt's advice the two stations in the cemetery were built as temporary structures, in the expectation that they would need to be rebuilt once the railway was operational and the issues with operating a railway of this unique nature became clearer.[32] Both were designed by Sydney Smirke, who presented his designs to the LNC in March 1854.[32]

Each station was built as a one-storey building around a square courtyard. The side adjacent to the railway line was left open, and wings extended from the building along the platform on each side. Other than the brick platform faces, chimneys and foundations, the stations were built entirely of wood.[32] Each station held first class and ordinary reception rooms for mourners, a first class and an ordinary refreshment room, and a set of apartments for LNC staff.[32] The refreshment rooms at both stations were licensed (permitted to sell alcohol).[85][note 10] The train crews would generally wait in these refreshment rooms until the trains were ready to return to London, and on at least one occasion (on 12 January 1867) the driver became so drunk that the fireman had to drive the train back to London.[86] This incident prompted a complaint from the LSWR and from that time the LNC provided the train crew with a free lunch, provided they drank no more than one pint of beer.[86]

In mid-1855 cellars were dug beneath the stations, and the coffin reception rooms at each station were converted into "pauper waiting rooms".[87] Neither station was equipped with gas or electricity; throughout their existence the buildings were lit by oil lamps and coal ranges were used for heating and cooking.[88][note 11] The platform faces themselves incorporated an indentation, one brick-width deep and the width of the courtyard.[32] This indentation facilitated the unloading of coffins from the lower levels of the hearse carriages.[89][90]

On arrival at the stations coffins would usually be unloaded onto a hand-drawn bier and pulled by LNC staff to the appropriate chapel.[89] While this was taking place the mourners were escorted to the waiting rooms at the station.[53] On arrival at the chapels first and second class funerals would generally have a brief service (third class funerals had a single service in the appropriate chapel for all those being buried).[89] For those burials where the funeral service had already been held at either a parish church or the LNC's London terminus the coffins would be taken directly from the train to the grave.[91]

North station

North station, serving Roman Catholics, Parsees, Jews and Nonconformist Christians as well as some groups with dedicated plots in the northern cemetery such as actors and Oddfellows, was the first station on the branch.[89][92] At the time the cemetery opened North station incorporated the lodgings of James Bailey, superintendent of the Nonconformist cemetery.[87] In 1861 Bailey became the sole cemetery superintendent and moved into a cottage elsewhere on the grounds, and his apartment was given to Richard Lee, a cemetery porter. Census records show Lee living at North station, until 1865 with his mother Ann and later with his wife Charlotte, until at least 1871.[87] A number of cemetery staff lived in the station apartment until the 1950s. By this time the railway itself had closed but the station's refreshment kiosk remained open.[93] Steps led from the 210-foot (64 m) long platform to a path leading to a chapel, on a hilltop behind the station.[73]

Between 1942 and 1944 large numbers of Allied service personnel were buried in the military section of Brookwood cemetery. On the authority of Thomas B. Larkin, Quartermaster General of the United States Army, 3,600 bodies of US servicemen were exhumed in January–May 1948 and shipped to the United States for reburial. The railway service had been suspended in 1941, and North station (renamed North Bar after the ending of rail services[32]) was used as a temporary mortuary to hold these bodies while awaiting shipment to the USA.[73]

On the retirement in 1956 of a Mr and Mrs Dendy, who operated the refreshment kiosk in the station building from 1948 to 1956 and lived in the station apartment, the building was abandoned.[73] It was demolished in the 1960s owing to dry rot.[73]

South station

The design of South station was broadly similar to that of North station. Unlike the platform steps of North station, the platform of South station had a ramp leading to an Anglican chapel at the northern end of the platform.[73] A shed adjacent to the station held hand-drawn biers, used to transport coffins around the large southern cemetery.[73] At the time the branch line opened the platform of South station was only 128 feet (39 m) long, far shorter than the 210-foot (64 m) platform of North station.[88] At some point the platform was greatly extended south from the station building to a total length of 256 feet (78 m), allowing equipment to be unloaded discreetly without disturbing users of the station.[88]

At the time of opening the apartment in the station housed George Bupell, superintendent of the Anglican cemetery. As with the North station, once James Bailey became sole cemetery superintendent in 1861 the use of the apartment was granted to a cemetery porter, and housed a succession of cemetery staff over the years. Following the suspension of railway services in 1941 the building was renamed South Bar,[32] and remained in use as a refreshment kiosk.[88] The last operators of the kiosk, Mr and Mrs Ladd, retired in the late 1960s and from then on the station building was used as a cemetery storeroom.[88] Around half the building was destroyed by fire in September 1972.[88] The building was popular with railway and architectural enthusiasts as a distinctive piece of Victorian railway architecture, but despite a lobbying campaign to preserve the surviving sections of the station the remaining buildings (other than the platform itself) were demolished shortly afterwards.[85][88] By the time of its demolition the "temporary" structure was 118 years old.[85]

Brookwood station

At the time the cemetery opened, the nearest railway station other than those on the cemetery branch was Woking railway station, 4 miles (6.4 km) away. As only one train per day ran from London to the cemetery stations and even that ran only when funerals were due to take place, access to the cemetery was difficult for mourners and LNC staff.[85] Although in the negotiations leading to the creation of the cemetery the LSWR had told the LNC that they planned to build a main line station near the cemetery, they had not done so.[94]

In 1863, with the cemetery fully operational and a planned new lunatic asylum near Brookwood likely to boost traffic, the LSWR agreed to build a mainline station at Brookwood, along with an improved Necropolis Junction and a goods yard, provided the LNC supplied the necessary land and built the approach road and stationmaster's house for the new station.[94] The new station, called Brookwood (Necropolis) railway station (the suffix was gradually dropped), opened on 1 June 1864.[94][95] A substantial commuter village grew around the northern (i.e. non-cemetery) side of the new station, and the station building (on the northern side of the tracks) was enlarged in 1890.[94] In conjunction with these works, a branch line was added in 1890 from a bay platform to the National Rifle Association's shooting range at Bisley, running west to the north of the LSWR main line before curving north to Bisley.[96][97]

In 1903 the quadrupling of the LSWR tracks necessitated a major rebuilding of the station. The down (westbound) platform was demolished, and a new 576-foot (176 m) long down platform was built, along with a second station building facing the cemetery, from which a footpath led across the cemetery branch's tracks and into the cemetery.[94]

London stations

A site for the London terminus near Waterloo was suggested by Sir Richard Broun. Its proximity to the Thames meant that bodies could be cheaply transported to the terminus by water from much of London, and the area was easily accessed from both north and south of the river by road. The arches of the huge brick viaduct carrying the LSWR into Waterloo Bridge station (now London Waterloo station) were easily converted into mortuaries. Broun also felt that the journey out of London from Waterloo Bridge would be less distressing for mourners; while most of the rail routes out of London ran through tunnels and deep cuttings or through densely populated areas, at this time the urban development of what is now south London had not taken place and the LSWR route ran almost entirely through parkland and countryside.[98] The LNC also contemplated taking over the LSWR's former terminus at Nine Elms railway station (which following the 1848 opening of the much more convenient Waterloo Bridge station was used only for goods traffic, chartered trains taking migrants to North America,[99] and the private trains of the royal family) as either the main or a secondary terminus.[100][101] Despite objections from local residents concerned about the effects of potentially large numbers of dead bodies being stored in a largely residential area,[30] in March 1854 the LNC settled on a single terminus in Waterloo and purchased a plot of land between Westminster Bridge Road and York Street (now Leake Street) for the site.[102] Architect William Tite and engineer William Cubitt drew up a design for a station, which was approved in June 1854.[98]

First London terminus (1854–1902)

Tite and Cubitt's design was based around a three-storey main building,[104] separated from the LSWR's main viaduct by a private access road beneath the LNC's twin rail lines, intended to allow mourners to arrive and leave discreetly, and avoid the need for hearses to stop in the public road.[105] The building housed two mortuaries, the LNC's boardroom and funerary workshops, and a series of separate waiting rooms for those attending first, second and third class funerals.[106] A steam-powered lift carried coffins from the lower floors to the platform level above.[107][note 12] Although the original London terminus did not have its own chapel, on some occasions mourners would not be able or willing to make the journey to a ceremony at Brookwood but for personal or religious reasons were unable to hold the funeral service in a London church. On these occasions one of the waiting rooms would be used as a makeshift funeral chapel.[108]

As the site of the station was adjacent to the arches of the LSWR's viaduct, it blocked any increase in the number of lines serving Waterloo station (renamed from Waterloo Bridge station in 1886). Urban growth in the area of what is now south west London, through which trains from Waterloo ran, led to congestion at the station and in 1896 the LSWR formally presented the LNC with a proposal to provide the LNC with a new station in return for the site of the existing terminus. The LNC agreed to the proposals, in return for the LSWR granting the LNC control of the design of the new station and leasing the new station to the LNC for a token rent in perpetuity, providing new rolling stock, removing any limit on the number of passengers using the Necropolis service, and providing the free carriage of machinery and equipment to be used in the cemetery.[109] Although the LSWR was extremely unhappy at what they considered excessive demands,[110] in May 1899 the companies signed an agreement, in which the LSWR gave in to every LNC demand. In addition the LSWR paid £12,000 compensation (about £1.36 million in terms of 2020 consumer spending power) for the inconvenience of relocating the LNC station and offices,[37][111] and agreed that mourners returning from the cemetery could travel on any LSWR train to Waterloo, Vauxhall or Clapham Junction.[60]

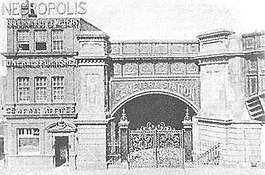

Second London terminus (1902–1941)

A site for the replacement terminus was bought by the LSWR in 1899, south of the existing site and on the opposite side of Westminster Bridge Road.[112] It was completed on 8 February 1902,[112] and the LSWR viaduct was widened to serve a greatly enlarged Waterloo station, destroying all traces of the original LNC terminus.[113]

The new building was designed for attractiveness and modernity to contrast with the traditional gloomy decor associated with the funeral industry.[114] A narrow four-storey building on Westminster Bridge Road held the LNC's offices. Behind it was the main terminal; this held a communal third-class waiting room,[115] mortuaries and storerooms,[114] the LNC's workshops,[116] and a sumptuous oak-panelled Chapelle Ardente, intended for mourners unable to make the journey to Brookwood to pay their respects to the deceased.[116] This building led onto the two platforms, lined with waiting rooms and a ticket office.[116]

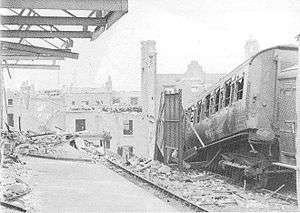

Destruction

During the Second World War Waterloo station and the nearby Thames bridges were a significant target for Axis bombing, and there were several near-misses on the station during the London Blitz of 1940–41.[115] Although there were several interruptions to the Necropolis train service owing to enemy action elsewhere on the line, the Necropolis station was undamaged during the early stages of the bombing campaign.[115] During the night of 16–17 April 1941, in one of the last major air raids on London,[note 13] bombs repeatedly fell on the Waterloo area. The rolling stock berthed in the Necropolis siding was burned, and the railway arch connecting the main line to the Necropolis terminus was damaged, but the terminal building itself remained unscathed.[117]

At 10.30 pm multiple incendiary devices and high explosive bombs struck the central section of the terminus building. While the office building and platforms survived, the workshops, driveway and Chapelle Ardente were destroyed, along with the third class waiting room.[117][118][note 14] The Southern Railway's Divisional Engineer inspected the damage at 2.00 pm on 17 April, and his report read simply "Necropolis and buildings demolished".[118] On 11 May 1941 the station was officially declared closed.[117][note 15]

The last recorded funeral party carried on the London Necropolis Railway was that of Chelsea Pensioner Edward Irish (1868–1941), buried on 11 April 1941.[55][note 16] The Southern Railway offered the LNC the temporary use of platform 11 or 12 of Waterloo station to allow the service to be continued,[55] but refused to allow the LNC to continue to sell cheap tickets to visitors travelling to and from the cemetery stations other than those involved in a funeral that day, meaning those visiting the cemetery other than members of funeral parties had little reason to choose the LNC's irregular and infrequent trains over the SR's fast and frequent services to Brookwood.[119][120] The LNC attempted to negotiate a deal by which genuine mourners could still travel cheaply to the cemetery on the 11.57 am service to Brookwood (the SR service closest to the LNC's traditional departure time), but the SR management, themselves under severe financial pressure owing to wartime constraints and damage, refused to entertain any compromise.[121]

Closure

In September 1945, following the end of hostilities, the directors of the LNC met to consider whether to rebuild the terminus and reopen the London Necropolis Railway. Although the main line from Waterloo to Brookwood had remained in use throughout the war and was in good condition, the branch line from Brookwood into the cemetery had been almost unused since the destruction of the London terminus.[117] With the soil of the cemetery causing the branch to deteriorate even when it had been in use and regularly maintained, the branch line was in extremely poor condition.[42][117]

Although the original promoters of the scheme had envisaged Brookwood Cemetery becoming London's main or only cemetery, the scheme had never been as popular as they had hoped.[54] In the original proposal, Richard Broun had calculated that over its first century of operations the cemetery would have seen around five million burials at a rate of 50,000 per year, the great majority of which would have utilised the railway.[15] In reality at the time the last train ran on 11 April 1941, almost 87 years after opening, only 203,041 people had been buried in the cemetery.[55] Before the outbreak of hostilities, increased use of motorised road transport had damaged the profitability of the railway for both the LNC and the Southern Railway.[113] Faced with the costs of rebuilding the cemetery branch line, building a new London terminus and replacing the rolling stock damaged or destroyed in the air raid, the directors concluded that "past experience and present changed conditions made the running of the Necropolis private train obsolete".[117] In mid-1946 the LNC formally informed the SR that the Westminster Bridge Road terminus would not be reopened.[119]

The decision prompted complicated negotiations with the SR over the future of the LNC facilities in London.[117] In December 1946 the directors of the two companies finally reached agreement.[122] The railway-related portions of the terminus site (the waiting rooms, the caretaker's flat and the platforms themselves) would pass into the direct ownership of the SR, while the remaining surviving portions of the site (the office block on Westminster Bridge Road, the driveway and the ruined central portion of the site) would pass to the LNC to use or dispose of as they saw fit.[117] The LNC sold the site to the British Humane Association in May 1947 for £21,000 (about £828,000 in terms of 2020 consumer spending power),[37] and the offices of the LNC were transferred to the Superintendent's Office at Brookwood.[117][123][note 17] The SR continued to use the surviving sections of the track as occasional sidings into the 1950s, before clearing what remained of their section of the site.[118]

While most of the LNC's business was now operated by road, an agreement on 13 May 1946 allowed the LNC to make use of SR services from Waterloo to Brookwood station for funerals, subject to the condition that should the service be heavily used the SR (British Railways after 1948) reserved the right to restrict the number of funeral parties on any given train.[43] Although one of the LNC's hearse carriages had survived the bombing it is unlikely that this was ever used, and coffins were carried in the luggage space of the SR's coaches.[43] Coffins would either be shipped to Brookwood ahead of the funeral party and transported by road to one of the mortuaries at the disused cemetery stations, or travel on the same SR train as the funeral party to Brookwood and be transported from Brookwood station to the burial site or chapel by road.[43]

Although the LNC proposed to convert the cemetery branch line into a grand avenue running from Brookwood station through the cemetery, this never took place.[42] The rails and sleepers of the branch were removed in around 1947,[42] and the trackbed became a dirt road and footpath.[124][note 18] The run-around loop and stub of the branch line west of Brookwood station remained operational as sidings, before being dismantled on 30 November 1964.[42] After the closure of the branch line the buildings of the two cemetery stations remained open as refreshment kiosks, and were renamed North Bar and South Bar.[32]

After closure

Following the 1947 nationalisation of Britain's railways, the use of the railway to transport coffins to Brookwood went into steep decline. New operating procedures required that coffins be carried in a separate carriage from other cargo; as regular services to Brookwood station used electric multiple unit trains which did not have goods vans, coffins for Brookwood had to be shipped to Woking and then carried by road for the last part of the journey, or a special train had to be chartered. The last railway funeral to be carried by British Rail anywhere was that of Lord Mountbatten in September 1979,[126] and from 28 March 1988 British Rail formally ceased to carry coffins altogether.[127] Since Mountbatten, the only railway funeral to be held in the United Kingdom has been that of former National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers General Secretary Jimmy Knapp, carried from London to Kilmarnock for burial in August 2001.[128]

Stations

Most of the site of the 1902 London terminus was built over with new office developments in the years following the end of the Second World War, but the office building on Westminster Bridge Road, over the former entrance to the station driveway, remains relatively unaltered externally although the words "London Necropolis" carved into the stone above the driveway have been covered.[113] Refurbishments and cleaning in the 1980s restored the facade of the building to an appearance similar to that of the time of its building.[113] Other than iron columns in Newnham Terrace which once supported the Necropolis Railway tracks,[113] and a surviving section of the internal driveway used as a car park,[113] the Westminster Bridge Road building is the only surviving part of the London Necropolis Railway in London.[114]

Brookwood station on the former LSWR line (now the South Western Main Line and the Alton Line) is little changed since the 1903 expansion and rebuilding.[124] It remains in use both by commuters from the village which has grown to the north of the railway line, and by visitors to the cemetery to the south of the line.[124] A small monument to the London Necropolis Railway, consisting of a short length of railway track on the former trackbed, was erected in 2007 outside the southern (cemetery-side) entrance to the station.[124]

The site of North station has significantly changed. The ornate mausoleum of Sharif Al-Hussein Ben Ali (d. 1998) stands directly opposite the remains of the platform.[129] The operators of the Shia Islamic section of the cemetery have planted Leylandii along the boundary of their section of the cemetery, which includes the platform of North station. Unless the trees are removed, the remains of the station will ultimately become hidden and destroyed by overgrowth.[129]

The land surrounding the site of South station and the station's two Anglican chapels were redundant following the closure of the railway. As part of the London Necropolis Act 1956 the LNC obtained Parliamentary consent to convert the disused original Anglican chapel into a crematorium, using the newer chapel for funeral services and the station building for coffin storage and as a refreshment room for those attending cremations.[130] Suffering cash flow problems and distracted by a succession of hostile takeover bids, the LNC management never proceeded with the scheme and the buildings fell into disuse.[130] The station building was demolished after being damaged by a fire in 1972, although the platform remained intact.[88]

Since 1982 the site of South station has been owned by the St. Edward Brotherhood, and forms part of a Russian Orthodox monastery.[129] The original Anglican chapel is used as a visitor's centre and living quarters for the monastery, while the larger Anglican chapel built in 1908–09 immediately north of the station is now the Russian Orthodox Church of St. Edward the Martyr, and houses the relics and shrine of Edward the Martyr, king of England from 975–978 AD.[131] The site of the former station buildings is now the main monastery building, while the platform itself remains intact and now marks the boundary of the monastic enclosure.[131]

Brookwood Cemetery and the LNC

The LNC continued to lobby the SR and its 1948 successor British Railways until the 1950s on the matter of cheap fares for visitors to the cemetery, but were unable to come to any agreement.[127] In 1957 the Southern Region of British Railways considered allowing the LNC to sell discounted fares of 7s 6d (compared to the standard rate of 9s 4d) for day return tickets from London to Brookwood. By this time most visitors to the cemetery were travelling by road. The LNC felt that the relatively minor difference between the fares would not be sufficient to attract visitors back to the railway, and the proposal was abandoned.[127]

With the area around Woking by this time heavily populated, the LNC's land holdings had become an extremely valuable asset, and from 1955 onwards the LNC became a target for repeated hostile takeover bids from property speculators.[130] In January 1959 the Alliance Property Company announced the successful takeover of the London Necropolis Company, bringing over a century of independence to an end.[132] Alliance Property was a property company with little interest in the funeral business, and the income from burials was insufficient to maintain the cemetery grounds. Brookwood Cemetery went into decline and the cemetery began to revert to wilderness.[132] This trend continued under a succession of further owners.[133]

The Brookwood Cemetery Act 1975 authorised the cemetery's owners (at that time Maximilian Investments) to sell surplus land within the cemetery's boundaries, leading to the construction of a major office development on the site of the former Superintendent's office, near the former level crossing between the northern and southern cemeteries.[129] The masonry works remained operational until the early 1980s, and were then converted into office buildings and named Stonemason's Court.[131] In March 1985 the cemetery was bought by Ramadan Güney, whose family still owns the cemetery as of 2011. The Guney family embarked on a programme of encouraging new burials in the cemetery, and of slowly clearing the overgrown sections of the cemetery.[134][135]

While it was never as successful as planned, Brookwood Cemetery remains the largest cemetery in the United Kingdom and one of the largest in the world.[136] Although not the world's only dedicated funeral railway line, the London Necropolis Railway was the first, the longest lasting and by far the best known.[33]

As well as forming a key element of Basil Copper's novel Necropolis (1980),[137] the railway and cemetery received widespread attention following the 2002 publication of Andrew Martin's novel The Necropolis Railway (2002). Both books were critically acclaimed and led to increased public interest in the London Necropolis Company and its railway operations.[138] It also plays a pivotal role in the sci-fi fantasy novel The Fuller Memorandum (2010) by Charles Stross.

See also

- Ffestiniog Railway, which operated funeral services (although not a dedicated funeral branch or station) from 1885–c. 1928 before the improvement of the road network in the area; the single hearse van used is preserved at Porthmadog Harbour railway station;[139]

- New Southgate Cemetery (formerly the Great Northern London Cemetery), the only other British cemetery to be (briefly) served by a dedicated funeral railway branch line (1861–63, possibly also briefly during 1866);[140] demolished in circa. 1904

- Rookwood Cemetery railway line in Sydney and Fawkner Crematorium and Memorial Park and Spring Vale Cemetery railway line in Melbourne, Australian cemetery railway systems closely modelled on the London Necropolis Railway which operated between 1867 and 1948, 1906 and 1939, and 1904 to 1950 respectively.[141]

Notes and references

Notes

- The names "London Necropolis" and "Brookwood Cemetery" were both used for the site. The tract of land was named "Brookwood Cemetery", while the company responsible for burials and maintenance used the name "London Necropolis".[16] The formal name of the company on its incorporation in 1852 was "The London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company". In 1927, with the proposed National Mausoleum still unbuilt, it was changed to "The London Necropolis Company".[17]

- Blomfield was speaking in 1842 about the use of railways to convey funeral parties in general, and not specifically criticising the Brookwood scheme.[22]

- The western end of the site was chosen as the land was most suitable for use as a cemetery, and the terrain best suited for the railway line. It was also the section of the site best served by existing roads.[28] The directors planned that if the initial cemetery was successful, the money raised would fund the drainage and redevelopment of the remaining 80% of the site to make it suitable for cemetery use and railway traffic.[27]

- Traditional English burial practice was for graveyards and cemeteries to be divided into an Anglican south and a Nonconformist north. The tradition derived from churchyard burials, where Church of England burials were conducted in the sunny area south of the church, and the unbaptised and those who did not want to be buried in an Anglican ceremony were buried in the shadowed area north of the church.[32]

- The Hore twins, along with the other burials on the first day, were pauper funerals and buried in unmarked graves.[34] The first burial at Brookwood with a permanent memorial was that of Lt. Gen Sir Henry Goldfinch, buried on 25 November 1854, the 26th person to be buried in the cemetery.[35] His is not the oldest gravestone in the cemetery, as on occasion gravestones were relocated and re-erected during the relocation of existing burial grounds.[36]

- The LNC charged extra for burials in some designated special sites in the cemetery.[46]

- Although these departure times varied slightly, over the 87 years of London Necropolis Railway operations they never deviated by more than 20 minutes.[49]

- At the time Brookwood Cemetery opened cremation was illegal in Britain. In 1879 Woking Crematorium was built in a section of the eastern end of the LNC's tract of land (i.e., the end furthest from the section in use as Brookwood Cemetery) bought from the LNC, but was only used for the experimental incineration of livestock until the 1884 trial of William Price established that human cremation was not unlawful. Golders Green Crematorium, the first crematorium near London, opened in 1902.[64][65]

- One of those executed, David Cobb, was not transferred to Plot E but was repatriated to the US and reburied in Dothan, Alabama in 1949.[71]

- It is documented that the refreshment rooms in the cemetery displayed signs reading "Spirits served here".[85]

- It is possible but unlikely that the South station building was supplied with gas and electricity in the last years of its operation as a refreshment kiosk.[88]

- Although there is no record of the steam engine being removed or damaged, by 1898 the coffin lift to platform level was worked by hand rather than steam-driven.[107]

- The air raid of 16 April 1941 was the single most damaging during the London Blitz in terms of loss of life, with 1,180 killed and 2,230 seriously injured. Over 150,000 incendiary bombs and 890 tons of high explosive were dropped on London over a 91⁄2 hour period, causing around 22,000 fires.[117]

- Although the station was destroyed on the night of 16–17 April, the last train had run on 11 April.[117]

- Some sources give an official closure date of 15 May. As the station building had been destroyed and the arches carrying the branch line into the station rendered unusable the previous month, the "closure date" is a technicality.[117]

- A second, unidentified, coffin was also carried on the last train. As the deceased's identity is not recorded, it is impossible to determine whether Irish or this unknown person was the last cadaver to be buried after being carried on the London Necropolis Railway.[55] Although the LNC conducted most of its business by road after the destruction of the London terminus, on occasion coffins and funeral parties were carried by the Southern Railway from Waterloo on the LNC's behalf, although funeral trains were never again operated by the LNC directly.[43]

- Although LNC operations were transferred to Brookwood, the LNC leased a building at 123 Westminster Bridge Road from the Southern Railway to serve as a London office. This building also served as the registered premises of the company.[113]

- Mitchell & Smith (1988) give a date of 1953 for the removal of the track,[125] but photographs from September 1948 show that the track had already been removed by this time.[42]

References

- Arnold 2006, p. 19.

- Arnold 2006, p. 20.

- Clarke 2006, p. 9.

- Arnold 2006, p. 44.

- Clarke 2004, p. 1.

- Arnold 2006, pp. 94–95.

- Arnold 2006, p. 112.

- Arnold 2006, p. 115.

- Connor 2005, p. 39.

- Arnold 2006, p. 111.

- Arnold 2006, p. 114.

- Arnold 2006, p. 120.

- Arnold 2006, p. 161.

- Arnold 2006, p. 160.

- Clarke 2006, p. 11.

- Clarke 2006, p. 12.

- Clarke 2006, p. 16.

- Brandon & Brooke 2008, p. 98.

- Clarke 2006, p. 131.

- Clarke 2006, p. 79.

- Clarke 2006, p. 13.

- Clarke 2006, p. 15.

- Brandon & Brooke 2008, p. 99.

- Clarke 2004, p. 4.

- Clarke 2006, p. 18.

- Clarke 2006, p. 17.

- Clarke 2006, p. 45.

- Clarke 2006, p. 51.

- Clarke 2006, p. 81.

- Clarke 2004, p. 7.

- Clarke 2006, p. 110.

- Clarke 2006, p. 61.

- Clarke 2006, p. 164.

- Clarke 2004, p. 13.

- Clarke 2004, pp. 13–14.

- Clarke 2006, p. 112.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Clarke 2006, p. 55.

- Clarke 2004, p. 11.

- Mitchell & Smith 1988, §33.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 55–57.

- Clarke 2006, p. 57.

- Clarke 2006, p. 99.

- Clarke 2006, p. 50.

- Clarke 2006, p. 101.

- Clarke 2006, p. 83.

- Clarke 2004, p. 16.

- Clarke 2006, p. 86.

- Clarke 2006, p. 87.

- Clarke 2006, p. 156.

- Clarke 2006, p. 113.

- Clarke 2006, p. 115.

- Clarke 2006, p. 104.

- Clarke 2006, p. 91.

- Clarke 2006, p. 95.

- Clarke 2006, p. 93.

- Clarke 2006, p. 162.

- Clarke 2006, p. 148.

- Clarke 2006, p. 150.

- Clarke 2006, p. 157.

- Clarke 2006, p. 159.

- Clarke 2006, p. 151.

- Clarke 2006, p. 152.

- Clarke 2006, p. 107.

- Arnold 2006, p. 233.

- Clarke 2006, p. 153.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 153–154.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 111–112.

- Clarke 2006, p. 111.

- Clarke 2004, p. 24.

- Clarke 2006, p. 126.

- "Brookwood American Cemetery and Memorial". American Battle Monuments Commission. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- Clarke 2006, p. 67.

- Clarke 2006, p. 147.

- Clarke 2006, p. 140.

- Clarke 2006, p. 141.

- Clarke 2006, p. 142.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 142–143.

- Clarke 2006, p. 143.

- Clarke 2006, p. 145.

- Clarke 2006, p. 135.

- Clarke 2006, p. 132.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 132–133.

- Clarke 2006, p. 133.

- Clarke 2006, p. 74.

- Clarke 2006, p. 128.

- Clarke 2006, p. 63.

- Clarke 2006, p. 69.

- Clarke 2006, p. 102.

- Mitchell & Smith 1988, §32.

- Clarke 2006, p. 103.

- Mitchell & Smith 1988, §31.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 63–67.

- Clarke 2006, p. 75.

- Mitchell & Smith 1988, §11.

- Mitchell & Smith 1988, §14.

- Mitchell & Smith 1988, §17.

- Clarke 2006, p. 19.

- Connor 2005, p. 20.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 19–21.

- Connor 2005, p. 38.

- Clarke 2006, p. 21.

- Clarke 2006, p. 26.

- Clarke 2006, p. 24.

- Clarke 2006, p. 25.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 21–23.

- Clarke 2006, p. 23.

- Clarke 2006, p. 117.

- Clarke 2006, p. 31.

- Connor 2005, p. 41.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 31–33.

- Clarke 2006, p. 33.

- Clarke 2006, p. 44.

- Clarke 2006, p. 35.

- Clarke 2006, p. 41.

- Clarke 2006, p. 37.

- Clarke 2006, p. 43.

- Connor 2005, p. 46.

- Clarke 2006, p. 97.

- Clarke 2006, p. 154.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 154–155.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 43–44.

- Clarke 2004, p. 28.

- Clarke 2006, p. 77.

- Mitchell & Smith 1988, §34.

- Clarke 2006, p. 178.

- Clarke 2006, p. 155.

- Clarke 2006, p. 179.

- Clarke 2006, p. 5.

- Clarke 2004, p. 30.

- Clarke 2006, p. 78.

- Clarke 2004, p. 31.

- Clarke 2004, p. 32.

- Clarke 2004, p. 35.

- Clarke 2004, p. 236.

- Brandon & Brooke 2008, p. 93.

- Clarke 2006, p. 173.

- Clarke 2006, p. 177.

- Clarke 2006, p. 183.

- Clarke 2006, p. 180.

- Clarke 2006, pp. 181–182.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Catherine (2006). Necropolis: London and its dead. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-0248-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brandon, David; Brooke, Alan (2008). London: City of the Dead. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-4633-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarke, John M. (2004). London's Necropolis. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3513-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarke, John M. (2006). The Brookwood Necropolis Railway. Locomotion Papers. 143 (4th ed.). Usk, Monmouthshire: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-85361-655-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Connor, J. E. (2005). The London & South Western Rly. London's Disused Stations. 5. Colchester: Connor & Butler. ISBN 978-0-947699-38-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1988). Woking to Alton. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-59-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Brookwood Cemetery, successor to the London Necropolis Company

- The Brookwood Cemetery Society, a group dedicated to the preservation and documentation of the cemetery

- Saint Edward Brotherhood, owners of the former South station site and of the Church of Saint Edward the Martyr

- Ruggeri, Amanda, The passenger train created to carry the dead. BBC 18, October 2016