Iterated logarithm

In computer science, the iterated logarithm of , written log* (usually read "log star"), is the number of times the logarithm function must be iteratively applied before the result is less than or equal to . The simplest formal definition is the result of this recurrence relation:

On the positive real numbers, the continuous super-logarithm (inverse tetration) is essentially equivalent:

i.e. the base b iterated logarithm is if n lies within the interval , where denotes tetration. However, on the negative real numbers, log-star is , whereas for positive , so the two functions differ for negative arguments.

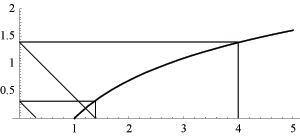

The iterated logarithm accepts any positive real number and yields an integer. Graphically, it can be understood as the number of "zig-zags" needed in Figure 1 to reach the interval on the x-axis.

In computer science, lg* is often used to indicate the binary iterated logarithm, which iterates the binary logarithm (with base ) instead of the natural logarithm (with base e).

Mathematically, the iterated logarithm is well-defined for any base greater than , not only for base and base e.

Analysis of algorithms

The iterated logarithm is useful in analysis of algorithms and computational complexity, appearing in the time and space complexity bounds of some algorithms such as:

- Finding the Delaunay triangulation of a set of points knowing the Euclidean minimum spanning tree: randomized O(n log* n) time.[1]

- Fürer's algorithm for integer multiplication: O(n log n 2O(lg* n)).

- Finding an approximate maximum (element at least as large as the median): lg* n − 4 to lg* n + 2 parallel operations.[2]

- Richard Cole and Uzi Vishkin's distributed algorithm for 3-coloring an n-cycle: O(log* n) synchronous communication rounds.[3][4]

- Performing weighted quick-union with path compression.[5]

The iterated logarithm grows at an extremely slow rate, much slower than the logarithm itself. For all values of n relevant to counting the running times of algorithms implemented in practice (i.e., n ≤ 265536, which is far more than the estimated number of atoms in the known universe), the iterated logarithm with base 2 has a value no more than 5.

| x | lg* x |

|---|---|

| (−∞, 1] | 0 |

| (1, 2] | 1 |

| (2, 4] | 2 |

| (4, 16] | 3 |

| (16, 65536] | 4 |

| (65536, 265536] | 5 |

Higher bases give smaller iterated logarithms. Indeed, the only function commonly used in complexity theory that grows more slowly is the inverse Ackermann function.

Other applications

The iterated logarithm is closely related to the generalized logarithm function used in symmetric level-index arithmetic. It is also proportional to the additive persistence of a number, the number of times someone must replace the number by the sum of its digits before reaching its digital root.

In computational complexity theory, Santhanam[6] shows that the computational resources DTIME — computation time for a deterministic Turing machine — and NTIME — computation time for a non-deterministic Turing machine — are distinct up to

Notes

- Olivier Devillers, "Randomization yields simple O(n log* n) algorithms for difficult ω(n) problems.". International Journal of Computational Geometry & Applications 2:01 (1992), pp. 97–111.

- Noga Alon and Yossi Azar, "Finding an Approximate Maximum". SIAM Journal on Computing 18:2 (1989), pp. 258–267.

- Richard Cole and Uzi Vishkin: "Deterministic coin tossing with applications to optimal parallel list ranking", Information and Control 70:1(1986), pp. 32–53.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L. (1990). Introduction to Algorithms (1st ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-262-03141-8. Section 30.5.

- https://www.cs.princeton.edu/~rs/AlgsDS07/01UnionFind.pdf

- On Separators, Segregators and Time versus Space

References

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001) [1990]. "3.2: Standard notations and common functions". Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-262-03293-7.