Loevestein faction

The Loevestein faction[1] (Dutch: Loevesteinse factie) or the Loevesteiners were a Dutch States Party in the second half of the 17th century in the County of Holland, the dominant province of the Dutch Republic. It claimed to be the party of "true freedom" against the stadtholderate of the House of Orange-Nassau, and sought to establish a purely republican form of government in the Northern Netherlands.[2][3][4]

History

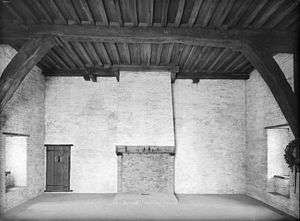

The name Loevestein refers to Loevestein Castle. There, stadtholder William II locked up six members of the States of Holland and West Friesland during his coup d'état of 30 July 1650. Amongst them was the burgomaster of Dordrecht, Jacob de Witt (father of Johan and Cornelis de Witt). After pressure by the States of Holland, they were already subsequently released between 17 and 22 August 1650.[2] Jacob de Witt lost all his functions, but when William II died several months after his coup, Jacob retrieved most of his functions. These events made the term Loevestein faction synonymous for pro-States regenten who opposed the stadtholderate. The De Witt family, too, walked over to the States camp after this incident.

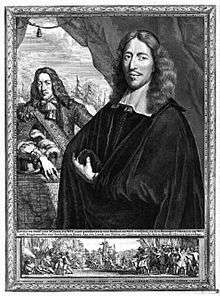

The term "Loevestein faction" was invented by their Orangist adversaries. It has been suggested that Jacob had 'poisoned' his sons with anti-Orange sentiments, and he allegedly told them every day to 'Gedenck aan Loevesteyn' ("Remember Loevestein"), although this is disputed. From the 1660s onwards, the Prince's supporters would start identifying the Brothers de Witt with earlier States supporters such as Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (executed for his opposition against Maurice of Nassau) and Hugo Grotius (sentenced to life imprisonment in Loevestein in 1619 at Maurice's instigation, but he escaped in a book chest in 1621). After the assassination of the Brothers de Witt in 1672, their allies started doing the same, reappropriating the word "Loevesteiner".

In the 18th century, van Oldenbarnevelt and Grotius were retroactively counted amongst the "heroes and martyrs of the Loevestein tradition". In the early 19th century, king William I preferred to let the factional struggles during the Dutch Republic be 'forgiven and forgotten', but amongst others the firmly Orangist historian Willem Bilderdijk on the one hand and the liberal historian Reinier Cornelis Bakhuizen van den Brink (calling himself a "Loevesteiner [...] to the bone") on the other, vehemently disagreed, and sought to rewrite the history of the Netherlands according to their own views.[4]

See also

- Patriots (Dutch Republic)

Literature

- Anti-Loevestein writings

- Genees-Middelen Voor Hollants-Qualen, Vertoonende De quade regeringe der Loevesteinse Factie ("Medicines for Holland's Illnesses, Showing the Evil Government of the Loevestein Faction") (1672). Antwerp: Willem Hendrik Wort.

- J. T La Fargue, Het waare karakter van den raad-pensionaris De Witt en der Loevesteinse-factie. Ontworpen uit onwraakbare Bewyzen, ter zuiveringe der vaderlandsche historie ("The True Character of Grand Pensionary De Witt and the Loevestein Faction. Composed from Irrefutable Evidence, to Cleanse the Fatherland's History") (1757). The Hague: Mattheus Gaillard.

- Pro-Loevestein writings

- Jan Wagenaar, Het egt en waar karakter van den heere raadpensionaris Johan de Witt. Getrokken uit de brieven van den graave d'Estrades en andere schriften; en overgesteld tegen het valsch en wanschaapen karakter, onlangs in 't licht gegeven. (The True and Real Character of Sir Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt. Compiled from the Letters of Count d'Estrades and Other Writings; and Opposed to the False and Misshapen Character Recently Presented.") (1757). Amsterdam: Isaak Tirion.

References

- Ward, Adolphus William; et al. (1908). The Cambridge Modern History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. Retrieved 16 March 2016., also called "Louvestein faction" in older English texts. Onnekink, David (2011). "The ideological context of the Dutch war (1672)". Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650-1750). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 131–144. ISBN 9781409419143. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Loevesteinse factie". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Encarta, s.v. "patriotten".

- N.C.F. van Sas, "Gedenck aan Loevesteyn" in De metamorfose van Nederland: van oude orde naar moderniteit, 1750-1900 (2004) 571–572. Amsterdam University Press.