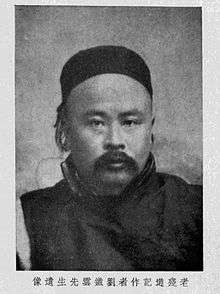

Liu E

Liu E (simplified Chinese: 刘鹗; traditional Chinese: 劉鶚; pinyin: Liú È; Wade–Giles: Liu E; also spelled Liu O; 18 October 1857 – 23 August 1909), courtesy name Tieyun (simplified Chinese: 铁云; traditional Chinese: 鐵雲; pinyin: Tiěyún; Wade–Giles: T'ieh-yün), was a Chinese writer, archaeologist and politician of the late Qing Dynasty.

Liu E 劉鶚 / 劉鉄雲 / 鴻都百煉生 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 October 1857 Dantu, Jiangsu |

| Died | 23 August 1909 (aged 51) Dihua, Xinjiang |

| Pen name | Hong Du Bai Lian Sheng Chinese: 鸿都百炼生 |

| Occupation | Writer, scholar, politician |

| Language | Chinese |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Period | late Qing era |

| Genre | Illustrated fiction |

| Notable works | The Travels of Lao Can |

Government and politics

Liu was a native of Dantu (modern day Zhenjiang). In the government he worked with flood control, famine relief, and railroads. He became disillusioned with official ideas of reform and became a proponent of private economic development modeled after western systems. During the Boxer Uprising he speculated in government rice, distributing it to the poor. He was cashiered for these efforts, but shrewd investments had left him wealthy enough to follow his pioneering archaeological studies and to write fiction.

Literature

The language in Liu E's novels borrowed illusions and images from classical Chinese literature and Liu E used symbolism in his novels. Therefore, his works appealed to readers who had a classical education and were considered sophisticated in their society.[1]

One of Liu's best known works is The Travels of Lao Can.

Oracle bone archeology and scholarship

In 1903 Liu published the first collection of 1,058 oracle bone rubbings entitled Tieyun Zanggui (鐵雲藏龜,Tie Yun's [i.e., Liu E] Repository of Turtles) that helped launch the study of oracle bone inscriptions as a distinct branch of Chinese epigraphy.[2]

Exile and death

Liu was framed for malfeasance related to his work during the Boxer Rebellion and was exiled in 1908, dying within the next year in Dihua of the Xinjiang Province (today known as Ürümqi).

Notes

- Doleželová-Velingerová, p. 724.

- Creamer, Thomas B. I. (1992), "Lexicography and the history of the Chinese language", in History, Languages, and Lexicographers, ed. by Ladislav Zgusta, Niemeyer, p. 108.

References

- Doleželová-Velingerová, Milena. "Chapter 38: Fiction from the End of the Empire to the Beginning of the Republic (1897–1916)" in: Mair, Victor H. (editor). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press, 13 August 2013. p. 697–731. ISBN 0231528515, 9780231528511.

- Shen, Tianyou, Encyclopedia of China, 1st ed.

- The Travels of Lao Ts'an, Liu T'ieh-yün (Liu E), translated by Harold Shadick, professor of Chinese literature in Cornell University. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1952. Reissued: New York; London: Columbia University Press, 1990. 277p. (A Morningside Book).

- The travels of Lao Can, translated by Yang Xianyi, Gladys Yang (Beijing: Panda Books, 1983; 176p.)

External links

- Works by E Liu at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Liu E at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)