Lipid bilayer mechanics

Lipid bilayer mechanics is the study of the physical material properties of lipid bilayers, classifying bilayer behavior with stress and strain rather than biochemical interactions. Local point deformations such as membrane protein interactions are typically modelled with the complex theory of biological liquid crystals but the mechanical properties of a homogeneous bilayer are often characterized in terms of only three mechanical elastic moduli: the area expansion modulus Ka, a bending modulus Kb and an edge energy . For fluid bilayers the shear modulus is by definition zero, as the free rearrangement of molecules within plane means that the structure will not support shear stresses. These mechanical properties affect several membrane-mediated biological processes. In particular, the values of Ka and Kb affect the ability of proteins and small molecules to insert into the bilayer.[1][2] Bilayer mechanical properties have also been shown to alter the function of mechanically activated ion channels.[3]

Area expansion Modulus

Since lipid bilayers are essentially a two dimensional structure, Ka is typically defined only within the plane. Intuitively, one might expect that this modulus would vary linearly with bilayer thickness as it would for a thin plate of isotropic material. In fact this is not the case and Ka is only weakly dependent on bilayer thickness. The reason for this is that the lipids in a fluid bilayer rearrange easily so, unlike a bulk material where the resistance to expansion comes from intermolecular bonds, the resistance to expansion in a bilayer is a result of the extra hydrophobic area exposed to water upon pulling the lipids apart.[4] Based on this understanding, a good first approximation of Ka for a monolayer is 2γ, where gamma is the surface tension of the water-lipid interface. Typically gamma is in the range of 20-50mJ/m2.[5] To calculate Ka for a bilayer it is necessary to multiply the monolayer value by two, since a bilayer is composed of two monolayer leaflets. Based on this calculation, the estimate of Ka for a lipid bilayer should be 80-200 mN/m (note: N/m is equivalent to J/m2). It is not surprising given this understanding of the forces involved that studies have shown that Ka varies strongly with solution conditions[6] but only weakly with tail length and unsaturation.[7]

The compression modulus is difficult to measure experimentally because of the thin, fragile nature of bilayers and the consequently low forces involved. One method utilized has been to study how vesicles swell in response to osmotic stress. This method is, however, indirect and measurements can be perturbed by polydispersity in vesicle size.[6] A more direct method of measuring Ka is the pipette aspiration method, in which a single giant unilamellar vesicle (GUV) is held and stretched with a micropipette.[8] More recently, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been used to probe the mechanical properties of suspended bilayer membranes,[9] but this method is still under development.

One concern with all of these methods is that, since the bilayer is such a flexible structure, there exist considerable thermal fluctuations in the membrane at many length scales down to sub-microscopic. Thus, forces initially applied to an unstressed membrane are not actually changing the lipid packing but are rather “smoothing out” these undulations, resulting in erroneous values for mechanical properties.[7] This can be a significant source of error. Without the thermal correction typical values for Ka are 100-150 mN/m and with the thermal correction this would change to 220-270 mN/m.

Bending Modulus

Bending modulus is defined as the energy required to deform a membrane from its natural curvature to some other curvature. For an ideal bilayer the intrinsic curvature is zero, so this expression is somewhat simplified. The bending modulus, compression modulus and bilayer thickness are related by such that if two of these parameters are known the other can be calculated. This relationship derives from the fact that to bend the inner face must be compressed and the outer face must be stretched.[4] The thicker the membrane, the more each face must deform to accommodate a given curvature (see bending moment). Many of the values for Ka in literature have actually been calculated from experimentally measured values of Kb and t. This relation holds only for small deformations, but this is generally a good approximation as most lipid bilayers can support only a few percent strain before rupturing.[10]

Curvature

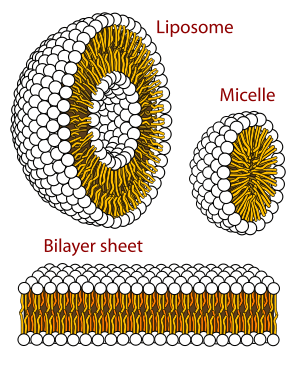

Only certain classes of lipids can form bilayers. Two factors primarily govern whether a lipid will form a bilayer or not: solubility and shape. For a self assembled structure such as a bilayer to form, the lipid should have a low solubility in water, which can also be described as a low critical micelle concentration (CMC).[5] Above the CMC, molecules will aggregate and form larger structures such as bilayers, micelles or inverted micelles.

The primary factor governing which structure a given lipid forms is its shape (i.e.- its intrinsic curvature).[4] Intrinsic curvature is defined by the ratio of the diameter of the head group to that of the tail group. For two-tailed PC lipids, this ratio is nearly one so the intrinsic curvature is nearly zero. Other headgroups such as PS and PE are smaller and the resulting diacyl (two-tailed) lipids thus have a negative intrinsic curvature. Lysolipids tend to have positive spontaneous curvature because they have one rather than two alkyl chains in the tail region. If a particular lipid has too large a deviation from zero intrinsic curvature it will not form a bilayer.

Edge Energy

Edge energy is the energy per unit length of a free edge contacting water. This can be thought of as the work needed to create a hole in the bilayer of unit length L. The origin of this energy is the fact that creating such an interface exposes some of the lipid tails to water, which is unfavorable. is also an important parameter in biological phenomena as it regulates the self-healing properties of the bilayer following electroporation or mechanical perforation of the cell membrane.[8] Unfortunately, this property is both difficult to measure experimentally and to calculate. One of the major difficulties in calculation is that the structural properties of this edge are not known. The simplest model would be no change in bilayer orientation, such that the full length of the tail is exposed. This is a high energy conformation and, to stabilize this edge, it is likely that some of the lipids rearrange their head groups to point out in a curved boundary. The extent to which this occurs is currently unknown and there is some evidence that both hydrophobic (tails straight) and hydrophilic (heads curved around) pores can coexist.[11]

References

- M. L. Garcia."Ion channels: Gate expectations." Nature. 430. (2004) 153-155.

- T. J. McIntosh and S. A. Simon."Roles of Bilayer Material Properties in Function and Distribution of Membrane Proteins." Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35. (2006) 177–198.

- T. M. Suchyna, S. E. Tape, R. E. Koeppe, O. S. Andersen, F. Sachs and P. A. Gottlieb."Bilayer-dependent inhibition of mechanosensitive channels by neuroactive peptide enantiomers." Nature. 6996. (2004) 235-240.

- D. Boal, "Mechanics of the Cell". 2002, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Israelachvili, J., Intermolecular and Surface Forces. 2nd ed. 2002: Academic Press.

- C. A. Rutkowski, L. M. Williams, T. H. Haines and H. Z. Cummins."The elasticity of synthetic phospholipid vesicles obtained by photon correlation spectroscopy." Biochemistry. 30. (1991) 5688-5696.

- W. Rawicz, K. C. Olbrich, T. McIntosh, D. Needham and E. Evans."Effect of chain length and unsaturation on elasticity of lipid bilayers." Biophysical Journal. 79. (2000) 328-39.

- E. Evans, V. Heinrich, F. Ludwig and W. Rawicz."Dynamic tension spectroscopy and strength of biomembranes." Biophysical Journal. 85. (2003) 2342-2350.

- S. Steltenkamp, M. M. Muller, M. Deserno, C. Hennesthal, C. Steinem and A. Janshoff."Mechanical properties of pore-spanning lipid bilayers probed by atomic force microscopy." Biophysical Journal. 91. (2006) 217-226.

- F. R. Hallett, J. Marsh, B. G. Nickel and J. M. Wood."Mechanical properties of vesicles: II A model for osmotic swelling and lysis." Biophysical Journal. 64. (1993) 435-442.

- J. C. Weaver and Y. A. Chizmadzhev."Theory of electroporation: A review " Biochemistry and Bioenergetics. 41. (1996) 135-160.