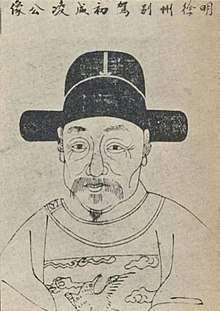

Ling Mengchu

Ling Mengchu (Chinese: 凌濛初; pinyin: Líng Méngchū; Wade–Giles: Ling Meng-ch'u; 1580–1644) was a Chinese writer of the Ming Dynasty. He is best known for his vernacular short fiction collections Slapping the Table in Amazement (拍案驚奇), I and II.[1][2]

Biography

Ling Mengchu was born into the Ling clan of Wucheng in northern Zhejiang province (modern day Wuxing District). His courtesy name was 'Xuanfang' (玄房) and his pseudonym was 'Chucheng' (初成).[2]

His ancestors were government officials. His grandfather was named Ling Yueyan (凌约言). He was a successful candidate in the highest imperial examinations of Ming Dynasty and in Nanjing served as an adjutant, managing legal affairs and prisons. Ling Mengchu's father was Ling Dizhi (凌迪知), styled Zhizhe (稚哲). He was a successful candidate in the highest imperial examinations in 1556. He first worked in the Labor ministry as a leader, managing projects, water conservation, farmlands and so on. This was an unimportant position, but Ling Dizhi was studious and serious. Soon he was appreciated by the emperor of Ming Dynasty, and became tongpan (通判) of Ding Zhou government and Tong Zhou government.[3]

At the time of Ling's birth, his family fortunes were declining. He had four brothers, and he was the fourth son in this family. He went to school when he was 12 and became Xiucai at age eighteen.[4] By 1605 his mother died and he failed the next level of exams. Afterwards, he wrote Break with Ju Zi (绝交举子书). In 1623, he was 44 years old. He met with minister of the Ministry of Rites Zhu Guozhen (朱国桢). After that meeting, Ling Mengchu decided to take up writing. In 1634 he worked as a country magistrate in Shanghai. In 1637 he wrote Wu Sao He Bian (吴骚合编) with Zhang Xudong. 1643 he was promoted to tongpan of Xuzhou government.

In addition family members were actively engaged in the printing business with a local specialty of books in polychrome. The Wucheng area was adjacent to the commercial and cultural areas of Hangzhou and Suzhou where reading materials were in increasing demand. Ling Mengchu was certainly a merchant businessman and also certainly a traditional scholar with civil service ambitions.

The business motive of the Ling family was originally discussed by Ling Mengchu’s contemporary Xie Zhaozhe (谢肇浙 1567-1624) in his Wu zazu (五雜俎 - Five Assorted Offerings). Such were the times. Ling repeatedly failed at the examinations and did not take a government post until he was fifty-four. Ling would finally perish in fighting against the Li Zicheng led rebels in 1644.[2] He is frequently associated with Feng Menglong.

Works

Ling’s Two Slaps collections of short stories (Slapping the Table in Amazement and Slapping the Table in Amazement, vol. 2) comprise a detailed composite portrait of his 17th century moral world, offering tales of virtue, vice, and adventure. Sometimes racy, often outrageous, and wildly imaginative, they have remained popular reading for centuries. While focusing on extraordinary events, the narratorial attitude alternates openness toward the unorthodox with reflexive Confucian conservatism, a mix also found in contemporaneous works such as Feng Menglong's Three Words trio of story collections and Zhang Yingyu's The Book of Swindles. Ling was most strongly influenced by Feng Menglong, whose success he acknowledged as having emboldened him to publish commercially.

In the prefatory material to his first short story collection he insisted it was infinitely more difficult to paint a likeness of a dog or horse one had actually seen than to render a ghost or goblin one had never observed (a quotation from Han Feizi).

Notes

- Yenna Wu, "Ling Meng-ch'u and the 'Two Slappings," in Victor Mair, (ed.), The Columbia History of Chinese Literature (NY: Columbia University Press, 2001). pp. 605- 610.

- Cihai: Page 369.

- Master and Masterpiece (published by Jinan Press, first published in 1997) page 1

- <Master and Masterpiece> (published by Jinan Press, first published in 1997)

References

- Ci hai bian ji wei yuan hui (辞海编辑委员会). Ci hai (辞海). Shanghai: Shanghai ci shu chu ban she (上海辞书出版社), 1979.

- James Scott, Rapp, trans., The Lecherous Academician,(1973), ISBN 0-85391-186-X

- Mengchu Ling. The Abbot and the Widow: Tales from the Ming Dynasty. (Norwalk: EastBridge, 2004). ISBN 1891936409

- Wen Jingen trans., Amazing Tales (Volume One), Panda Books, 1998. ISBN 7-5071-0398-6

- Perry W. Ma trans., Amazing Tales (Volume Two), Panda Books, 1998. ISBN 750710401X

Further reading

- Ling Mengchu, Slapping the Table in Amazement: A Ming Dynasty Story Collection. Translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2018.

- Carpenter, Bruce E., 'The Ming Short Story Collection "P'ai-an ching-ch'i."' Tezukayama Daigaku Jinbunkagakubu Kiyo (Tezukayama University Journal of Humanities), Nara, Japan, 2000, pp. 41–111.

- Goodrich and Fang ed., Dictionary of Ming Biography 1368-1644 ( bio. by Li Tienyi), New York,1976, vol. 1, pp. 930–931.