Lill's method

In mathematics, Lill's method is a visual method of finding the real roots of polynomials of any degree.[1] It was developed by Austrian engineer Eduard Lill in 1867.[2] A later paper by Lill dealt with the problem of complex roots.[3]

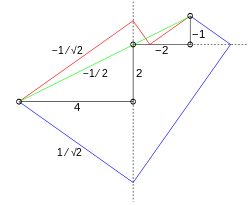

Lill's method involves expressing the coefficients of a polynomial as magnitudes of segments at right angles to each other, starting from the origin, creating a path to a terminus, then finding a non-right angle path from the start to the terminus reflecting or refracting on the lines of the first path.

Description of the method

To employ the method a diagram is drawn starting at the origin. A line segment is drawn rightwards by the magnitude of the first coefficient (the coefficient of the highest-power term) (so that with a negative coefficient the segment will end left of the origin). From the end of the first segment another segment is drawn upwards by the magnitude of the second coefficient, then left by the magnitude of the third, and down by the magnitude of the fourth, and so on. The sequence of directions (not turns) is always rightward, upward, leftward, downward, then repeating itself. Thus each turn is counterclockwise. The process continues for every coefficient of the polynomial including zeroes, with negative coefficients "walking backwards". The final point reached, at the end of the segment corresponding to the equation's constant term, is the terminus.

A line is then launched from the origin at some angle θ, reflected off of each line segment at a right angle (not necessarily the "natural" angle of reflection), and refracted at a right angle through the line through each segment (including a line for the zero coefficients) when the angled path does not hit the line segment on that line.[4] The vertical and horizontal lines are reflected off or refracted through in the following sequence: the line containing the segment corresponding to the coefficient of then of etc. Choosing θ so that the path lands on the terminus, the negative of the tangent of θ is a root of this polynomial. For every real zero of the polynomial there will be one unique initial angle and path that will land on the terminus. A quadratic with two real roots, for example, will have exactly two angles that satisfy the above conditions.

The construction in effect evaluates the polynomial according to Horner's method. For the polynomial the values of , , are successively generated. A solution line giving a root is similar to the Lill's construction for the polynomial with that root removed.

In 1936 Margherita Piazzola Beloch showed how Lill's method could be adapted to solve cubic equations using paper folding.[5] If simultaneous folds are allowed then any nth degree equation with a real root can be solved using n–2 simultaneous folds.[6]

See also

- Carlyle circle, which is based on a slightly modified version of Lill's method for a normed quadratic.

References

- Dan Kalman (2009). Uncommon Mathematical Excursions: Polynomia and Related Realms. AMS. pp. 13–22. ISBN 978-0-88385-341-2.

- M. E. Lill (1867). "Résolution graphique des équations numériques de tous degrés à une seule inconnue, et description d'un instrument inventé dans ce but". Nouvelles Annales de Mathématiques. 2. 6: 359–362. (online copy)

- M. E. Lill (1868). "Résolution graphique des équations algébriques qui ont des racines imaginaires". Nouvelles Annales de Mathématiques. 2. 7: 363–367. (online copy)

- Phillips Verner Bradford, Sc.D.. Visualizing solutions to n-th degree algebraic equations using right-angle geometric paths. Archived May 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Thomas C. Hull (April 2011). "Solving Cubics With Creases: The Work of Beloch and Lill" (PDF). American Mathematical Monthly: 307–315. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.118.04.307.

- Roger C. Alperin; Robert J. Lang (2009). "One-, Two-, and Multi-Fold Origami Axioms" (PDF). 4OSME. A K Peters.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lill's method. |

- Bradford, Phillips Verner. "Extending Lill's Method of 1867". Visualizing solutions to n-th degree algebraic equations using right-angle geometric paths. www.concentric.net. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Animation for Lill's Method

- Mathologer video: "Solving equations by shooting turtles with lasers"