Liliosa Hilao

Liliosa Hilao (March 14, 1950 – April 5, 1973) was a Filipina student activist who was killed while under government detention during Martial Law in the Philippines, and is remembered as the first prisoner to die in detention during martial law in the Philippines.[1]. She was a student of Communication Arts in the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila.[2]

Liliosa Hilao | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 14, 1950 Bulan, Sorsogon, Philippines |

| Died | April 5, 1973 (aged 23) Quezon City, Philippines |

| Nationality | Filipino |

| Occupation | Student journalist, Activist |

| Known for | First prisoner to die in detention during martial law in the Philippines[1] |

Personal Life

Liliosa Hilao was born on March 14, 1950. She was the seventh of nine children and had seven sisters and one brother.[3]

Hilao was a consistent honor student in elementary and high school.[2]

Extracurricular activities

Hilao was an editor in her university's paper "Hasik."[2] She was the student president of the communication arts department. She was also a representative to PLM’s student central government.[2] Among other things, she was a secretary of the Women’s Club of Pamantasan. She was also a member of the College Editors Guild of the Philippines. She also formed the Communication Arts Club in her university.[2]

Hilao was known to be sickly, so she never took part in student protests. However, she showed her opinions through pieces of writing she did for her student paper at the PLM. Some of her works include "The Vietnamization of the Philippines” and “Democracy is Dead in the Philippines under Martial Law.” These works were indicative of her stance on martial law.[4]

Arrest and death

Arrest of Liliosa

The Philippine Constabulary raided the Hilao residence on April 4, 1973. They identified themselves to be part of the Philippine Constabulary Anti-Narcotics Unit (CANU). A man by the name of Lt. Arturo Castillo proclaimed himself as the team leader of the raiding party. According to an official letter from Hilao's family, only a Philippine Constabulary identification card was presented as proof of their claim. No warrant or search order was presented to the family for the entirety of the raid. Hilao herself was not yet present at this time. She only arrived later that evening. Upon her arrival, Liliosa was subjected to extreme violence by Lt. Castillo. According to the official letter, Lt. Castillo repeatedly beat her. Family members were stopped from attempting to intervene as they were threatened by the unit. In the morning of April 5, 1973, Liliosa would be handcuffed and taken by the CANU unit to their office at Camp Crame for questioning.

Arrest of Josefina

Hilao's sister, Josefina, was also arrested. Josefina would also be taken to Camp Crame. Josefina saw Hilao but was not permitted to speak to her. However, Josefina saw that parts of Hilao's face were said to be beaten and bloodied, an indication that she was being tortured and abused during her stay.[5]

Death

On April 7, three days after Liliosa’s arrest, Mrs. Alice Hilao Gualberto, one of her sisters, received a phone call. She was informed that Liliosa was in critical condition and that she has been confined at the Camp Crame Station Hospital due to serious injuries. She would later find Hilao in the emergency room of the Station. Hilao's face was disfigured. Several notable injuries and bruises were found all over her body. These include several needle puncture marks on her left arm and forearm, and "an opening at her throat.” The medical equipment used by Liliosa did not seem to function properly. No medical staff was tending to her. According to the official letter from the family, the room that she was being held in smelled strongly of formalin. Alice, having seen Liliosa for a few minutes, would then be quickly taken to the CANU Office. She met with Josefina there. They would later be informed by Lt. Castillo that Liliosa had died.[5]

A necropsy report by the Philippine Constabulary Crime Laboratory would later list cardio-respiratory arrest as the cause of her death.[5] Following her death, the Philippine Constabulary gave an amount of 2200 pesos to the family of Liliosa for burial expenses. The family has refused to spend the money since it was offered.[5]

Hilao was running for cum laude honors before she was killed.[2] After her death, a vacant seat was reserved for her during the ceremonies.[2] She was also awarded posthumous cum laude honors.[2]

Aftermath

According to the authorities, Hilao killed herself by drinking muriatic acid. They declared her case closed. However, her friends and family did not believe that the military had nothing to do with her death.[4]

After the People Power Revolution of 1986 and the overthrowing of President Marcos, there were several lawsuits filed against the president for torture. Among these lawsuits was one filed by a relative of Hilao, alleging that Hilao was killed after she had been "beaten, raped, and scarred by muriatic acid."[6]

This case was the first in the United States to bring a former president of another country into trial, although the jurisdiction was established in 1789 by the Alien Tort Statute.[7] In 1986, the court initially dismissed the case, referring to the “act of state doctrine.” This act provides immunity to a head of state or an incumbent president. Upon hearing the dismissal, the Philippine government filed a brief of amicus curiae to impel the US courts’ jurisdiction over the case. The government fought against the defendants’ claims that “they knew nothing” or that “they were not aware of the human rights abuses.” The government regularly sent documents against these claims. These documents were updates on executions and torture sessions of political detainees that Marcos received regularly during his presidency.[8]

In 1996, the Court of Appeals in Southern California ultimately ruled in favor of Hilao. The court charged almost $2 billion to the Marcos family for the damages caused to almost 10,000 human rights victims. According to Davis, after the decision was made final, the Marcos family concealed their property by holding it in dummy corporations.[7]

However, the possibility of these court cases being considered as part of the judicial business of US courts is still being debated.[6] Furthermore, the functionality of the Philippine Supreme Court is questionable at best. According to Tate and Haynie, Marcos's crony majority had a secure power over the Supreme Court.[9] Tate and Haynie claim that there is sufficient cause and evidence that shows that at least some justices feared for the "Supreme Court's institutional survival, if not their personal safety, as a result of the president's potential wrath."[9]

Legacy

Activists during the 1980s sought to replace the old women role models of the Philippines. These activists supported women revolutionaries against Spain and political activists who fought the Marcos Regime. As the old mantra of expecting women to accept "a life of suffering" was heavily criticized, activists advocated new mantras like "Hindi kailangan magtiis" ("It is not necessary to endure"), and "Know yourself, trust yourself, respect yourself." In particular, the former role models of Maria Clara, Sisa, and Juli were recognized as stereotypes that needed to be replaced in favor of women revolutionaries and political activists such as Liliosa Hilao.[10]

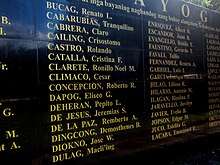

Liliosa Hilao's name is on the Bantayog ng mga Bayani's Wall of Remembrance for martyrs and heroes of martial law.[11][12]

There is a street named after her in Bulan, Sorsogon, where she was born.[11]

References

- Montalvan, Antonio, II. "Remember Liliosa Hilao as we vote".

- Medina, Kate Pedroso, Marielle. "Liliosa Hilao: First Martial Law detainee killed".

- Hilao - Gualberto, Alice (2017). Liliosa Hilao. Philippines: Ateneo de Naga Press.

- http://www.bantayog.org/?p=1059

- “Appendix A: The Case of Liliosa Hilao and the Hilao Family,” Arkibongbayan.org (2008): 101.

- Debra Cassens Moss, “Marcos Suits: Plaintiffs claim torture by former Philippines president,” American Bar Association (1989): 44.

- Doug Davis, “Speaking Truth to the Power in the Philippines,”Haverford Fall (2015): 39-43.

- Mendoza, Meynardo. "Is Closure Still Possible for the Marcos Human Rights Victims?" Social Transformations: Journal of the Global South 1, no. 1 (2013): 115-137.

- C. Neal Tate and Stacia L. Haynie, “Authoritarianism and the Functions of Courts: A Time Series Analysis of the Philippine Supreme Court, 1961-1986,” Law & Society Review (1993): 735.

- Mina Roces and Louise Edwards, “Women’s Movements in Asia - Feminisms and Transnational Activism” Routledge (2010): 42.

- Malay and Rodriguez (2015). Ang Mamatay nang Dahil sa 'Yo: Heroes and Martys of the Filipino People in the Struggle Against Dictatorship 1972-1986 (Volume 1). Ermita, Manila, Philippines: Historical Commission of the Philippines. ISBN 9789715382700. OCLC 927728036.

- "Martyrs and Heroes". Bantayog ng mga Bayani. Retrieved April 4, 2018.