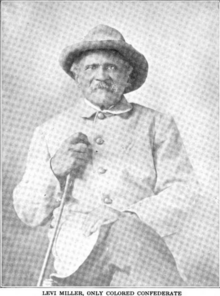

Levi Miller (Virginia)

Levi Miller (January 9, 1836 – February 25, 1921) was a preacher and farmer from Virginia. During the American Civil War, Miller was a manservant for his owner's brother, a Confederate Army captain, and may have been enrolled as a regular soldier after the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864. Miller's service is frequently used as an example of a black man who served as a soldier in the Confederate Army.

Levi Miller | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 9, 1836 |

| Died | February 25, 1921 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | farmer, preacher |

Early life

Levi Miller was born a slave on January 9, 1836 in Rockbridge County, Virginia[1] near Hayes Creek[2] and Brownsburg.[3] He had European,[2] African, and Native American ancestry.[1] At birth he was owned by Anne Maria McChesney McBride, widow of Col. Isaiah McBride.[2] He was religious and a gifted orator and began preaching to other slaves in the area.[1]

Civil War

In 1861, when the American Civil War started, Miller was owned by Anne's son, Robert McBride.[3] In September 1861, Robert's brother, Captain John J. McBride of Company E of the Fifth Texas Infantry Regiment in the Confederate Army, secured Miller as a personal servant. When Captain McBride was wounded in the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August 1862, Miller attended him in the hospital until his recovery. McBride recovered and Miller attended him at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862 and in the Suffolk Campaign the next spring.[1]

Miller was with McBride when General Robert E. Lee led the Confederate Army into Pennsylvania in his Gettysburg Campaign. In Pennsylvania, Miller was urged to desert by people in that northern state where slavery had been abolished since 1780. Miller and the rest of the Fifth Texas were detached from Lee's Army of Northern Virginia to Georgia and Tennessee along with the rest of General James Longstreet's corps, under which they fought. In the western theater, Miller was present at the Battle of Chickamauga and the Chattanooga and Knoxville Campaigns through the winter of 1864.[1]

In the spring of 1864, Longstreet returned to Lee in Virginia, and McBride and Miller to their regiment. At the Battle of the Wilderness, the Fifth Texas was a part of a charge wherein Captain McBride had both legs broken and was believed to be mortally wounded on the morning of May 6, 1864. Captain J. E. Anderson of Company C reported that Miller was with the wagon train and did not hear of McBride's injuries until he arrived at Spottsylvania Court House on May 8. On the 10th, during the Battle of Spottsylvania Court House, Miller was bringing rations to McBrides' company and was forced to run across an open field under fire from Union sharpshooters. Miller was told not to cross the field again in daylight and was instead directed to attend the ailing McBride. In the afternoon, the Union forces showed signs that they would attack and Miller asked for a gun and ammunition and was at Captain Anderson's side for the attack, which included hand-to-hand combat when the Union reached the Confederate breastworks.[1]

After the fight, another member of Company C (Jim Swindler[3]) proposed Miller be made a full member, and with the support of the rest of the company, Anderson enrolled Miller. That evening, Miller returned to Captain McBride who had been taken to a hospital at Charlottesville, Virginia where the pair remained until October 1865. Although not expected to survive the war, McBride lived until 1880, and Anderson later said; "He owed his life to Levi Miller's good nursing."[1]

Postbellum

After the war, Anderson worked to gain for Miller a full soldiers pension for his service based on muster rolls which Anderson claimed to have in his own possession.[4] However, as of 2013, researchers have not found Miller on any muster rolls collected by the Confederate government. That is, his service may not have been officially accepted as blacks were not permitted to enlist as soldiers.[5]

Miller was present at the 1913 reunion of the Battle of Gettysburg. Racial tension at the time meant that while the black press did mention Miller's special case, it did not mention the numerous black Union veterans who attended, a fact that has led some to say that the only black soldier present was a Confederate.[6] Later in life, Miller lived at Frederick County, Virginia and worked as a water dipper for mineral springs tourists at Capon Springs, Virginia and Rock Enon Springs, Virginia. He purchased land at Opequon, Virginia and farmed an orchard. He never married and was a member of the Methodist church. He died on February 25, 1921 and was buried in Lexington, Virginia.[4]

Legacy

The existence of black Confederate soldiers is a controversial subject, and Miller has frequently been a center of the controversy.[4] This controversy includes whether or not he was officially mustered in, and in which battles he participated, and in what capacity.[5]

References

- Ellis, Edward Sylvester. Library of American History: From the Discovery of America to the Present Time, Volume 7. Jones Brothers, 1918 p211-212 accessed April 24, 2016 at https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=BCLYAAAAMAAJ

- Confederate Veteran: Published Monthly in the Interest of Confederate Veterans and Kindred Topics, Volume 29. 1921 - Confederate States of America, page 358, accessed April 24, 2016 at https://books.google.com/books?id=wDBEAQAAMAAJ

- [No Headline]. Richmond Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), Monday, March 11, 1912, Page: 3

- Barrow, Charles Kelly, Segars, J.H. Black Southerners In Confederate Armies: A Collection of Historical Accounts Pelican Publishing Company, 31 Jan 2007 p196-197

- Williams, Richard, Jr. Lexington, Virginia and the Civil War. The History Press, 12 Mar 2013 p 124

- Gannon, Barbara A. The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic. Univ of North Carolina Press, 2011