Leucochloridium paradoxum

Leucochloridium paradoxum, the green-banded broodsac, is a parasitic flatworm (or helminth) that uses gastropods as an intermediate host. It is typically found in land snails of the genus Succinea.

| Leucochloridium paradoxum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leucochloridium paradoxum, parasite in Succinea putris | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. paradoxum |

| Binomial name | |

| Leucochloridium paradoxum (Carus, 1835) | |

Morphology

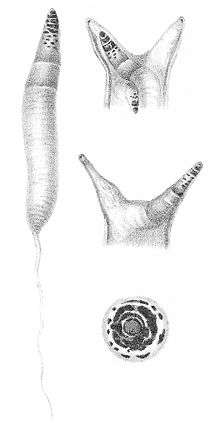

Leucochloridium species are very similar in appearance as adults. Many of them lack a hard structure and have a variety of ranges in sizes. The most common way to differentiate between Leucochloridium species is by looking at the broodsacs and banding patterns. L. paradoxum typically exhibits broodsacs that have green bands with dark brown and black spots.[1] During development, the parasite has different sizes and shapes. L. paradoxum eggs are brown colored and exhibit an oval shape.[2] The miracidia during the first stage of development are clear and elongated. Once the miracidia transform into sporocysts, they appear as broodsacs that infect the snail hosts in their eyes and begin to pulsate green, yellow, and red. The sporocysts turn into cercaria (juveniles) that have a tail, along with a digestive tract that is lined with an excretory bladder that extends into the tail. The tail of a cercaria has finfolds on the top and bottom and setae on the sides. Cercaria also have two eyespots. At the end of the cycle, the adults appear as worms that have spines and are dorsally flattened, with suckers in order to attach to the definitive host.[3]

Life cycle

The worm in its larval, miracidia stage, travels into the digestive system of a snail to develop into the next stage, a sporocyst. The sporocyst grows into long tubes to form swollen "broodsacs" filled with dozens to hundreds of cercariae. These broodsacs invade the snail's tentacles (preferring the left, when available), causing a brilliant transformation of the tentacles into a swollen, pulsating, colorful display that mimics the appearance of a caterpillar or grub.

The broodsacs seem to pulsate in response to light intensity, and in total darkness they do not pulse at all.[4] Infection of the tentacles of the eyes seems to inhibit the perception of light intensity. Whereas uninfected snails seek dark areas to prevent predation, infected snails have a deficit in light detection, and are more likely to become exposed to predators, such as birds. In a study done in Poland, 53% of infected snails stayed in more open places longer, sat on higher vegetation, and stayed in better lit places than uninfected snails. Only 28% of the uninfected snails remained fully exposed for the duration of the observation period.[5]

Birds are the definitive hosts for this parasitic worm. The cercariae develop into adult distomes in the digestive system of the bird; these adult forms sexually reproduce and lay eggs, which are released from the host via the bird's excretory system. These droppings are then consumed by snails to complete the creature's life cycle. Overall the life cycle is similar to that of other species of the genus Leucochloridium.

The resulting behavior of the flatworm is a case of aggressive mimicry, where the parasite vaguely resembles the food of the host; this gains the parasite entry into the host's body. This is unlike most other cases of aggressive mimicry, in which only a part of the host resembles the target's prey and the mimic itself then eats the duped animal.

Habitat

L. paradoxum are found in moist areas, such as the forests of North America and Europe, where their intermediate and definitive hosts such as Succinea snails and various birds (crows, jays, sparrows and finches) are found.

Distribution

Leucochloridium paradoxum was originally reported from Germany;[6] other locations include Norway[1] and Poland.[5]

Hosts

intermediate hosts:

hosts:

- birds

- Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) – experimental[1]

References

- T. A. Bakke (April) 1980. A revision of the family Leucochloridiidae Poche (Digenea) and studies on the morphology of Leucochloridium paradoxum Carus, 1835. Systematic Parasitology, Volume 1, Numbers 3-4. 189-202.

- Schmidt, G.D. (2000). Foundations in Parasitology, 6th ed. McGraw-Hill.

- Fried, B. (1997). Advances in Termatode Biology. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Edwin J. Robinson, Jr. (December 1947). "Notes on the Life History of Leucochloridium fuscostriatum n. sp. provis. (Trematoda: Brachylaemidae)". The Journal of Parasitology. 33 (6): 467–475. doi:10.2307/3273326. JSTOR 3273326. PMID 18903602.

- W. Wesołowska, T. Wesołowski, Journal of Zoology (October) 2013. Do Leucochloridum sporocysts manipulate the behaviour of their snail hosts? August 2013. Journal of Zoology. Issue 292, 2014: 151-5.

- S.P. Casey, T.A. Bakke, P.D. Harris & J. Cable (November) 2004. Use of ITS rDNA for discrimination of European green- and brown-banded sporocysts within the genus Leucochloridium Carus, 1835 (Digenea: Leucochloriidae). Systematic Parasitology. Volume 56, Number 3: 163-168.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leucochloridium paradoxum. |

- Leucochloridium paradoxum, Animal Diversity Web

- Distome (Leucochloridium paradoxum), The Living World of Molluscs

- Infecting a Snail: Life Cycle of the Grossest Parasite, Wired Magazine