Lerista labialis

The southern sandslider (Lerista labialis) is a species of skink or Scincidae. The species is endemic to Australia and widespread across the continent, being most commonly found within sandy termite mounds. This is where they take safe refuge from the harsh Australian climate and various ground predators.

| Lerista labialis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Lerista |

| Species: | L. labialis |

| Binomial name | |

| Lerista labialis Storr, 1971 | |

Description

The southern sandslider is a small skink, with a snake-like body and tail. It is red to brown in colour with a darker brown line on the side, being very similar to Lerista bipes. The skink has no fore limbs and the hind limbs are small.[2] The southern sandslider has one supraocular (scales lying above the eyes) between the eyes and no supraciliaries (small scales along the outer margin of the upper eyelid).[2]

An adult female southern sandslider is generally much longer than an adult male. The females can reach approximately 38 to 60 mm (snout-to-vent) in length. The males only reach between 37 and 55 mm (snout-to-vent) in length.[3]

Taxonomy

There are eight synonym for the southern sandslider, these include:[4]

- Lerista labialis (STORR 1971: 69)

- Lerista labialis (COGGER 1983: 174)

- Rhodona rolloi (WELLS & WELLINGTON 1985: 37 (fide SHEA & SADLIER 1999))

- Lerista labialis (GREER 1990)

- Lerista labialis (COGGER 2000: 523)

- Gaia labialis (WELLS 2012: 202)

- Gaia rolloi (WELLS 2012: 206)

- Lerista labialis (WILSON & SWAN 2010)

Distribution

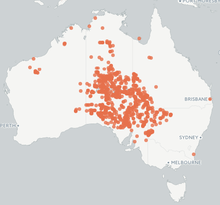

Southern sandsliders are found throughout the desert plains of Western Australia, the Northern Territory, Western Queensland and New South Wales.[5]

Southern sandsliders are most commonly found within the dune crests. This is mainly due to the suitability of this habitat in that it provides them with optimum temperatures, an adequate supply of food and the vegetation sparseness results in soft sandy areas that can aid in the reduction of energy costs (being able to move easily).[6]

Ecology and habitat

Southern sandsliders are fossorial, nocturnal (night-active), and terrestrial. They have a very narrow preferred body temperature range, ranging between 21–36 °C. They are found within dunes not only for the availability of food but for its thermoregulation. The southern sandslider swims through the loose sand of termite mounds.[7]

They are abundant in sandy deserts [7] with vegetation cover that is sparse on dune crests. This benefits the species allowing for unrestrained burrowing. Dunes provide an optimum temperature for the survival of the skinks as well as providing their food source.[6]

Reproduction

The southern sandsliders breed throughout summer, however the Lerista species tend to breed in winter during the dry season. They lay shelled eggs within November and February with the clutch size generally being an average of 2. The southern sandsliders sex cannot be determined by an external examination, the only way to determine the sex of the individual is through internal examination.[3]

Diet

Southern sandsiders have diets that consume mostly termites, and this makes up at least 78% of their diet, with the last 22% resulting in invertebrate classes including that of Hemiptera, Neuroptera etc.[3] The southern sandsliders catch their food by foraging below the ground surface [8]

Southern sandsliders forage late at night to the early morning between the surface and just below finding termites and other invertebrates. Not only do they ingest termites and invertebrates, the sandsliders also consume sand. The sand is ingested and is used to aid in the digestion.[6]

Overall, the termites can offer a reliable food source for the southern sandslider. With the increase in rainfall, the southern sandslider benefits from this. The increase in rainfall impacts on the Spinifex species, these species become more abundant with the increase in water availability, spinifex is the diet of termites. With an increase of food availability for the termites, these will cause an increase of termite population. Thus, as the southern sandsliders pray becomes more abundant so will the southern sandslider.[3]

Southern sandsliders are not affected by the seasonal changes but are rain dependent on their food availability, however they will source other species of prey if they need to. They do not need to drink; as they receive water and re-hydrate through the food they eat.[9]

Predators

The Southern sandslider take refuge in dunes to protect themselves from surface-active predators and also the harm of the extreme temperatures within its environment. There are two main predators of the southern sandslider, these are the snake Simoselaps fasciolatus and the skink Eremiascincus fasciolatus.[6]

Threats

There are currently no major threats for the Southern sandslider, their protection status is considered as least concerned wildlife.[10]

References

- Cowan, M., Teale, R., How, R., Cogger, H. & Zichy-Woinarski, J. 2017. Lerista labialis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T109476584A109476589. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T109476584A109476589.en. Downloaded on 20 June 2020.

- Cogger, Harold (2014). Reptiles and amphibians of Australia. Collingwood, VIC: CSIRO Publishing.

- Greenville, A. C.; Dickman, C. R. (2005). "The ecology of Lerista labialis in the Simpson Desert: reproduction and diet". Journal of Arid Environments. 60: 611–625. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2004.07.010.

- Uetz, Peter; Hallermann, Jakob (18 April 2017). "The reptile database".

- Uetz, Peter (2017). "Encyclopedia of Life".

- Greenville, Aaron; Dickman, Chris (2009). "Factors affecting habitat selection in a specialist fossorial skink". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 97: 531–544. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01241.x.

- Wilson, Steve K (2010). Australian Lizards A Natural History. Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing.

- Robin, Libby; Dickman, Chris; Martin, Mandy (2011). Desert Channels. Queensland: CSIRO Publishing.

- Free, Carissa (2009). "Role of the Field River as a refuge for small vertebrates in the Simpson Desert". The University of Queensland, Animal Studies.

- Uetz, Peter (2017). "Lerista labialis Storr, 1971 — Southern Sandslider". Atlas of Living Australia.