Leonid Kharitonov (actor)

Leonid Vladimirovich Kharitonov (Russian: Леонид Владимирович Харитонов; 1930–1987) was a Soviet actor. He played in the films Private Ivan, Ivan Brovkin on the State Farm and Ulitsa polna neozhidannostey. He was awarded Honoured Artist of the RSFSR in 1972.

Leonid Kharitonov | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | Leonid Vladimirovich Kharitonov 19 May 1930 |

| Died | 20 June 1987 (aged 57) |

| Occupation | actor |

| Years active | 1954–1986 |

| Spouse(s) | (1) Svetlana Kharitonova, actress (1942–2004) (2) Gemma Osmolovskaya (1938), actress (3) Yeugenia Gibova (1942–2004), drama student[1] |

Life

See image. He was born in Leningrad on 19 May 1930, USSR, and died in Moscow on 20 June 1987, aged 57.[2][3]

Career

Training

In early life he was ambivalent about an acting career. Although he took part in amateur productions, and in the ninth grade applied to theatre school, he nevertheless chose to study law for a year at university, while continuing theatrical performance in his spare time. "In the play The Inspector, he rocked the entire city of Leningrad; he played Bobchinsky and it was after this role that he again seriously considered an acting career." That summer, the Moscow Art School toured in Leningrad and offered auditions at his school. Kharitonov secretly attended, and was accepted.[3][4]

Overview of acting career

He graduated from the Nemirovich-Danchenko studio school at the Moscow Art Theatre in 1954. This was the Gorky Art Academic Theatre. After graduating from the studio school he continued working as an actor at the same theatre. He was an actor with the Academic Art Theatre in the name of M. Gorky, or Gorky Theatre, from 1954 to 1962, but then he left this theatre and in 1962–1963 he performed with the Theatre of Lenin Komsomol and with the Pushkin Theatre. But in 1963 he returned to the Gorky Art Academic Theatre. He was a film actor from 1954: his first role was Boris Gorikov in the movie School of Courage, while he was still an acting student.[3][4]

Early career and characterisations

In 1955 Kharitonov became a public idol after Private Ivan was screened throughout the country. He was the object of much fan mail, and appeared privately to many local audiences in clubs, schools, factories and stadia. "His fame was such that the actor could not walk down the street."[5] Kharitonov was a multi-dimensional performer who created a new type of Russian cinematic character: the charming bad egg, which he developed in his characterisations of Brovkin, the policeman Vasya Shaneshkin and his later heroic characters.[4] "It was skill, hard work, professionalism and above all perception which allowed this sophisticated actor to play so convincingly this simple country boy, Brovkin." Much of this was the effect of his training with the psychological acting school of MAT.[6] Private Ivan was followed in 1958 by Ivan Brovkin on the State Farm (see critical commentary below).[3]

Later career

With age, Kharitonov appeared in fewer films; he did not relish playing older men. However, sometimes he does appear in later movies grey and stout. For this reason of gradual absence from movies, in the 1980s Leonid Kharitonov was almost forgotten as a film actor although he continued performing at his native Moscow Art Theatre, as was the case during almost all his acting life.[3][4]

Private life

In private life he was said to live modestly.[4] He was married three times, first to Svetlana Kharitonov the character actress of the 1950s and 1960s. He met his second wife, the actress Gemma Osmolovskaya, on the set of The Street is Full of Surprises, and they had a son Alexei Khartionov who is now a scientist-programmer. His third wife was his student at the Moscow Art Theatre school.[1][3]

Illness

In later years Kharitonov was seriously ill. In the summer of 1980, during the Moscow Olympics, he suffered a first stroke. Then, while filming From the Life of the Chief of Criminal Investigation on 4 July 1984 this was followed by a second stroke. His health could not bear the news of the crisis of the Moscow Art Theatre in the summer of 1987. On 20 June 1987, the day of its division into two parts which was a very hard and dramatic time for the theatre, Kharitonov died the same day from his third stroke which occurred in the drama theatre. He was buried in Moscow in plot number 50 of Vagankovskoye cemetery.[1][3][4][5]

Theatrical performances

The following is a selection of Kharitonov's theatrical roles:[6]

The Forgotten Friend (1956) – Gosh

The Pickwick Papers (1956) – Joe

The Lower Depths (1956) – Alyosha

The Devil's Disciple (1957) – Christy[7]

The road through the Sokolniki (1958) – Aleshka Vronsky – image

Three Fat Men (1961) – Dr. Gaspar

Mutiny (1977) – Caravan

So we will win! (1981) – Fist

We, the undersigned – Explorer

The Village Stepanchikovo – Evgraf Ezhevikin

Peace to the huts, war to the palaces

Days of the Turbins – Lariosik

Goodbye, boys – Sasha Krieger

Dead Souls – Chichikov

House number 6

As he left, look – Fedor[3]

Filmography

The following is a selection of his films:

He was a supporting actor in Vasyok Trubachyov i yego tovarishchi (1955) and the romance Otryad Trubachyova srazhayetsya (1957).[8] He played Fedul VI in Fire, Water, and Brass Pipes (1968).[9][10] He played the part of Dobchinsky in the comedy Incognito from St. Petersburg (1977).[11] In 1979 he acted in Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears, and A Few Days from the Life of I. I. Oblomov. In Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears he appears in cameo as himself, as part of the setting for the character Rudolf (Yuri Vasilyev) who is a television cameraman and first lover of the protagonist Ekaterina (Vera Alentova). Kharitonov was at that time ubiquitous on Soviet television, and therefore represented the contemporary celebrity media zeitgeist. This cameo part is not unimportant, as director Vladimir Menshov said: "The uniqueness of the movie Moscow does not believe in tears lies in the fact that there are no bit parts."[3][12][13]

He played the Tsar in Along Unknown Paths(1982). He acted in: Iz Zhizni Nachalnika Ugolovnogo Rozyska (1983); Auktsion (1983); Postoronnim Vkhod Razreshyon (1986); Khorosho Sidim! (1986).[2] He was also in the movie New Year's Abduction which featured the song Dark-Eyed Cossack Girl, publicised by his namesake and friend the bass singer Leonid Kharitonov.[3][14]

Full filmography

- 1954 Courage School (Boris Gorik)

- 1955 Vasek trumpeter and his comrade (counsellor Mitya Bourtsev)

- 1955 Private Ivan (Russian: Солдат Иван Бровкин) (Ivan Brovkin) - image [15]

- 1955 Son (Andrew Goriaev) - image

- 1956 Good luck! (Andrey Averin)

- 1957 Next to us (laid off workers)

- 1957 Detachment Trubacheva fight (counsellor Mitya Bourtsev)

- 1957 Street Full of Surprises (Vasya Shaneshkin)

- 1959 Ivan Brovkin on the State Farm (Ivan Brovkin na tseline) (Ivan Brovkin)[16]

- 1960 Let Light (TV film, Efimkov)

- 1961 Long day (Lesch, excavator)

- 1961 Two lives (shoemaker)

- 1962 How to make toast (short, Grechkin)

- 1962 Kapron network (Valka, captain of the river tug Swan)

- 1963 Pitiable fate (short)

- 1964 All for you (Vorobushkin)

- 1967 Places still here (naval)

- 1968 Fire, Water, and Brass Pipes (Fedulov VI)

- 1969 Robbery (TV)

- 1969 New Year's Abduction (Новогоднее похищение) [14]

- 1972 Fakir hour (Trofim)

- 1977 Incognito from St. Petersburg (Dobchinsky)

- 1978 Incidental passengers (companion to the mixed feed)

- 1978 Vanity of vanities (James A.)

- 1979 Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (Russian: Москва слезам не верит; translit. Moskva slezam ne verit) (Leonid Kharitonov)[17][18]

- 1979 A few days from the life of Oblomov (Russian: Несколько дней из жизни И. И. Обломова) (Luka Savich)[19]

- 1979 Father and Son (Dorofeyka)

- 1980 Houses for forest (Bogomolov)

- 1980 Gigolo and Gigoletta

- 1981 Charm with secrets (baleen whales)

- 1982 Young Russia (Longinov)

- 1982 Along Unknown Paths (Tsar Makar)

- 1982 Charodei (Russian: Чародеи) (Amatin)[20]

- 1983 Auction (Yegorych)

- 1983 Eternal Call (Yegor Kuzmich Dedyukhin)

- 1983 Quarantine (military in the zoo)

- 1983 From the life: head of criminal investigations (grandfather Stepan)

- 1985 Bagrationi

- 1986 Sitting good! (grandfather)

- 1986 Inside allowed (neighbour Professor)[6][21][22][23][24][25]

Cartoon voiceovers

1969 In a country unlearned lessons (Cat)[6]

Reviews and critical commentaries

Von Geldern review

"Honor of being the first film to break postwar taboos went to the far more modest The Soldier Ivan Brovkin (1955), directed by Ivan Lukinskii and ignored by film historians. Essentially a story about a nice young Russian boy drafted into the war, the film de-elevated the war film to a level accessible to common viewers, without challenging them to confront its pain. Played by Leonid Kharitonov, whose lyrical performance of several songs from the movie made him an all-Soviet heart throb, Brovkin opened the way for more adventurous films. Similar in story line but very different in treatment was the 1959 film Ballad of a Soldier, directed by Grigorii Chukhrai, which uses the tale of a young soldier on leave from the war to convey its futility and tragedy."James von Geldern[26]

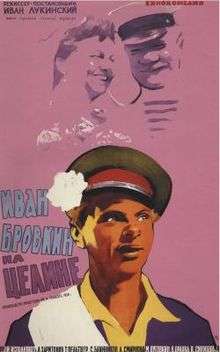

Critical commentary on Ivan Brovkin Na Tseline poster

The 1958 poster on the left illustrates the innocent face of the Brovkin character as performed by the sophisticated actor Kharitonov. It does this by contrasting the bland expression of the face with the shockingly modern (for 1958) complementary colours of the composition.[27] The pictorial style predates the complementary colourist Andy Warhol's first exhibition of 1962, and demonstrates that it was part of the source-culture for that artist's work, which he called "artificial colour".[28] The idea of re-working printed portraiture with gouache paints goes back to the previous century to such artists as Degas.[29] The greyed-out sketch of the supporting actors in the top half of the poster serves to represent and encourage the audience's pleasure at seeing the Brovkin character on screen again. The poster contains another compositional joke or trick, as it appears to ignore the rule of thirds on the vertical axis, while actually fulfilling that visual requirement on the horizontal axis, although discreetly. This cleverness again parallels Kharitonov's clever but hidden acting skills.

See also

- List of Soviet films

- List of Soviet films of the year by ticket sales

References

- "Who is Who". Kharitonov, Leonid (biography and filmography) (in Russian). 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "IMDbPro". Leonid Kharitonov page. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- Razzakov, F. (2007). The light of the gone out stars (in Russian). Moscow: EKSMO edition. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- "Calend.ru". Leonid Kharitonov (biography) (in Russian). Events Calendar. 2005–2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Narod.ru". Photo of grave of Leonid Vladimirovich Kharitonov (in Russian). Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "Cinematology: Narod.ru". Leonid Kharitonov unofficial website (in Russian). Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- Possibly this was George Bernard Shaw's ironically Christ-like character, Dudgeon

- "IMDb". Otryad Trubachyova srazhayetsya (1957). Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- "IMDb". Ogon, voda i... mednye truby (1968). Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- "divx planet". Ogon, voda i... mednye truby (1968). Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- "IMDb". Inkognito iz Peterburga. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- "Peoples.ru". Vladimir Menshov interview: "Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears" after 25 years (in Russian). 2005. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- "Kinoglaz.fr". pp. Leonid Kharitonov. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- "Kino-teatr.ru". New Year's Abduction (in Russian). 2006–2009. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- "IMDb". Soldat Ivan Brovkin (1955). 1990–2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "IMDb". Ivan Brovkin na tseline (1958). 1990–2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "IMDb". Moskva slezam ne verit (1980). 1990–2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- Trailer for "Moscow does not believe in tears" (1979) on YouTube

- "IMDb". Neskolko dney iz zhizni I.I. Oblomova (1980) A few days in the life of Ivan Oblomov. 1990–2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "IMDb". Charodei (1982). 1990–2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- "Kino-teatr.ru". Filmography of Leonid Kharitonov (in Russian). Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Russiancinema.ru". Filmography of Leonid Kharitonov (in Russian). Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Rudata.ru". Filmography of Leonid Kharitonov (in Russian). Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Videolala". Filmography of Leonid Kharitonov (wrong photo used here) (in Russian). Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Vh1.com". Filmography of Leonid Kharitonov (in Russian). Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- Von Geldern, James (2009). "Seventeen Moments in Soviet History". pp. 1956: War films: The Cranes Are Flying. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- McEvoy, Bruce (2002). "Handprint Media". Color (in Spanish and English). U.S.A.: Handprint Media. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- "Color Vision & Art". Andy Warhol's Marilyn Prints: see voice recording. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- Griffiths, A. (1985). Degas: monotypes, Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Hayward Gallery 1985. Arts Council of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

External links

- Russian Wikipedia page for Leonid Vladimirovich Kharitonov: includes filmography in Russian

- Leonid Kharitonov on IMDb

- Filmset photos of Kharitonov in Soldier Ivan Brovkin and Son

- Kharitonov in "Street is full of surprises" (1957) on YouTube

- Kharitonov in "Kak rozhdajutsja tosty" (1962) on YouTube

- Narod.ru: unofficial website for Leonid Kharitonov in Russian