Leatherman (vagabond)

The Leatherman (ca. 1839–1889) was a particular vagabond, famous for his handmade leather suit of clothes, who traveled a circuit between the Connecticut River and the Hudson River, roughly from 1857 to 1889. Of unknown origin, he was thought to be French-Canadian, because of his fluency in the French language, his "broken English", and the French-language prayer book found on his person after his death. His identity remains unknown, and controversial. He walked a 365-mile route year after year. His repeating route took him to certain towns in western Connecticut and eastern New York, returning to each town every 34–36 days.

Life

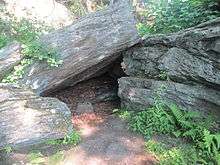

Living in rock shelters and "leatherman caves", as they are now locally known,[1] he stopped at towns along his 365-mile loop about every five weeks for food and supplies.[2] He was dubbed the "Leatherman" as his adornment of hat, scarf, clothes, and shoes were handmade leather.[3]

An early article in the Burlington Free Press, dating to April 7th, 1870 refers to him as the "Leather-Clad Man", it also states that he spoke rarely and when addressed would simply speak in monosyllables. According to contemporary rumors, he hailed from Picardy, France.[4]

Fluent in French, he communicated mostly with grunts and gestures, rarely using his broken English. When asked about his background, he would abruptly end the conversation.[5][6] Upon his death, a French prayer book was found among his possessions.[3][6] He declined meat on Fridays, giving rise to speculation that he was Roman Catholic.[7]

It is unknown how he earned money. One store kept a record of an order: "one loaf of bread, a can of sardines, one-pound of fancy crackers, a pie, two quarts of coffee, one gill of brandy and a bottle of beer".[3][8]

Leatherman was popular in Connecticut. He was reliable in his rounds, and people would have food ready for him, which he often ate on their doorsteps.[6][9] Ten towns along the Leatherman's route passed ordinances exempting him from the state "tramp law" passed in 1879.[1]

Health

The Leatherman survived blizzards and other foul weather by heating his rock shelters with fire. Indeed, while his face was reported to be frostbitten at times during the winter, by the time of his death he had not lost any fingers, unlike other tramps of the time and area.[10] The Connecticut Humane Society had him arrested and hospitalized in 1888, which resulted in a diagnosis of "sane except for an emotional affliction" and release, as he had money and desired freedom. His ultimate demise was from cancer of the mouth due to tobacco use.[3][8] His body was found on March 24, 1889 in his Saw Mill Woods cave on the farm of George Dell in the town of Mount Pleasant, New York[11] near Ossining, New York.[5]

Grave

His grave is in the Sparta Cemetery, Route 9, Ossining, New York. The following inscription was carved on his original tombstone:

FINAL RESTING PLACE OF

Jules Bourglay

OF LYONS, FRANCE

"THE LEATHER MAN"

who regularly walked a 365-mile route

through Westchester and Connecticut from

the Connecticut River to the Hudson

living in caves in the years

1858–1889

His grave was moved further from Route 9. When the first grave was dug up, no traces were found of the Leatherman's remains, only some coffin nails, which were reburied in a new pine box, along with dirt from the old grave site. Nicholas Bellantoni, a University of Connecticut archaeologist and the supervisor of the excavation, cited time, the effect of traffic over the shallow original gravesite, and possible removal of graveside material by a road-grading project for the complete destruction of hard and soft tissue in the grave.[12] The new tombstone, installed May 25, 2011, simply reads, "The Leatherman."

Identity controversy

The Leatherman's former tombstone read, "Final resting place of Jules Bourglay of Lyons, France, 'The Leather Man'…", and he is identified with that name in many accounts.[1][13] However, according to researchers, including Dan W. DeLuca,[14] and his New York death certificate, his identity remains unknown.[15] This name first appeared in a story published in the Waterbury Daily American, August 16, 1884, but was later retracted March 25, 26 and 27, 1889 and also in The Meriden Daily Journal, March 29, 1889.[2][9] DeLuca was able to get a new headstone installed, when the Leatherman's grave was moved away from Route 9 to another location within the cemetery on May 25, 2011. The new brass plaque simply reads "The Leatherman."[16]

Exhumation and reburial

The Leatherman's original grave in Sparta Cemetery was within 16 feet of Route 9.[17][18] His remains were exhumed and were reburied at a different site in the cemetery on May 25, 2011. No visible remains were recovered during the exhumation. Rather, coffin nails and soil recovered from the original burial plot were reburied at the new site. Part of the reason for the exhumation process was to test his remains to determine his origins. He had been rumored to be of French descent but there were several conflicting reports.

Towns visited

His circuit took in the following towns:[5]

- Brewster

- North Salem

- Ridgefield

- Branchville

- Georgetown

- Redding

- Danbury

- Woodbury

- Watertown

- Thomaston

- Terryville

- Bridgewater

- Waterbury

- Bristol

- Forestville

- New Britain

- Berlin

- Old Saybrook

- Guilford

- Branford

- East Haven

- New Haven

- Stratford

- Bridgeport

- Trumbull

- Norwalk

- New Canaan

- Stamford

- Greenwich

- White Plains

- Armonk

- Chappaqua

- Ossining

- Mount Kisco

- Bedford Hills

- Pound Ridge

- Yorktown

- Peekskill

- Somers

- Derby

- Woodbridge

- Naugatuck

- Hamden

- Southington

- Burlington

- Middletown

- Meriden

- Portland

- Wilton

Geocaching and letterboxing

Many of the locations on Leatherman's route in Connecticut and New York have geocaches[19] as well as letterboxes[1] near them.

Popular media

- Leatherman inspired a song by Pearl Jam, "Leatherman." It was a B-side of the single "Given to Fly," from the 1998 album Yield.[2]

- Leatherman was the subject of a 1984 video documentary which was shown on Connecticut Public Television. It can be found on YouTube.

- In 1965, on his program "Perception," Dick Bertel interviewed Mark Haber (1899-1994) about the Leatherman on Channel 3, WTIC-TV (WFSB since 1974) in Hartford, Conn. Video on YouTube, [20]

References

- Connecticut State Forests – Seedling Letterbox Series Clues for Mattatuck State Forest (retrieved September 23, 2007)

- Hudson Valley Ruins (retrieved July 21, 2006)

- Samantha Hunt, Jules Bourglay, Notable Walker. McSweeney's Internet Tendency, 11/2002 Archived 2005-09-20 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved July 21, 2006)

- "A Leather-Clad Hermit". The Burlington Free Press. April 7, 1870.

- History of Redding (retrieved July 21, 2006)

- NY Hudson Valley (retrieved July 21, 2006)

- Piece broadcast on (US) National Public Radio, in Connecticut, 19 Dec 2008

- Canning, Jeff and Wally Buxton, History of the Tarrytowns, Harbor Hill Books 1975

- Research by Dan W. DeLuca Archived 2006-12-06 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved July 21, 2006)

- DeLuca, Dan (2008). The Old Leather Man: Historical Accounts of a Connecticut and New York Legend. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6862-5

- DeLuca, Dan (2008). The Old Leather Man: Historical Accounts of a Connecticut and New York Legend. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, pp. 107, 113. ISBN 978-0-8195-6862-5

- Jim Fitzgerald: "Wanderer From 1800S Gets More Peaceful NY Grave.", boston.com, 25 May 2011

- "Leatherman's Cave, Watertown, CT". Archived from the original on August 8, 2009. Retrieved 2007-08-29.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) (retrieved September 23, 2007)

- LeMoult, Craig. "Search for Clues Only Deepens 'Leatherman' Mystery". Vermont Public Radio. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- DeLuca, Dan (2008). The Old Leather Man: Historical Accounts of a Connecticut and New York Legend. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8195-6862-5.

- "Search For Clues Only Deepens 'Leatherman' Mystery". National Public Radio. May 26, 2011.

- Dan Brechlin (3 January 2011). "Leather Man body may yield clues". The Record-Journal. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- Sam Cooper (29 November 2010). "Who was the Leather Man? Experts hope forensic tests will solve mystery". The Republican-American. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- Leatherman's Circuit (retrieved September 23, 2007)

- Bertel, Dick (14 February 1965). "The Life and Legend of the Old Leather Man". Perception. Hartford, Connecticut. WTIC-TV, Channel 3 (WFSB today). Retrieved 6 April 2020.

External links

- "Old Leather Man" - Stories of the 364 Mile Man

- Old Leather Man and James F. Rodgers

- New York Times - The Story of an Old Man and the Road

- Dan DeLuca interviewed

- The Leatherman

- Leatherman's Cave in Watertown

- Connecticut forest & Parks

- The Leatherman's Loop

- Cold Spots: The Legend of the Leatherman